![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

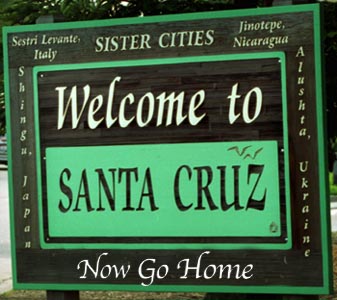

A Cause Without Champions

Santa Cruz County doesn't have enough affordable housing--and no one wants to hear about it

By Jessica Lyons

SANTA CRUZ is being sold to the highest bidder. Even those not currently scanning apartment listings for a bedroom--or a closet--to rent know the numbers. The housing market is tougher than a cowhide chew.

Forty-seven percent of Santa Cruz renters are unable to afford a two-bedroom apartment, according to a September 1999 study by the National Low Income Housing Coalition. The latest figures by the National Association of Home Builders say only 19 percent of the county's population can afford to buy a home in the area.

It's a market only Adam Smith could love.

Housing prices have since gone up, and for February, the median price tag on a single-family home was $415,000, according to the Santa Cruz Association of Realtors. With construction costs rising, buildable land scarce and low-income rentals increasingly rare, the problems are daunting. Silicon Valley's booming economy (and subsequent housing shortage) and UC-Santa Cruz's student-population goals also tax the demand for housing while limiting the supply.

Apparently, Santa Cruzans are starting to take note. According to a study of 400 voters released last week by the city of Santa Cruz, 75 percent of city residents surveyed rated the high cost of housing as a "very serious" problem. Traffic congestion and affordable housing top the list. Forty-two percent rate the need for affordable housing as the most important problem facing the city, compared with only 20 percent in 1998. In addition, 63 percent either strongly or somewhat favor some kind of rent control.

"If this doesn't highlight the need for affordable housing, I don't know what does," says Santa Cruz Mayor Keith Sugar, adding that building market-rate homes won't cut it. "People here don't need market rate. They can't afford market rate. We could build market-rate houses till the cows come home in Santa Cruz County, and it's really not going to drive the cost of housing down."

Although overwhelming numbers of people say the city needs more low-income housing, their support starts to taper off once the questions about how to provide such housing get more specific. Although 63 percent said they would pay more taxes to provide affordable housing for low-income people, only 45 percent said they would strongly favor rent control. Similarly, 47 percent said they would strongly favor establishing a low-income housing trust fund.

Perhaps most troubling is that low-income housing has become a cause without champions and without majority support in local governing bodies. Progressives and moderates alike speak loudly about the need for low-income housing, but mention adding high-density housing, developing agricultural land or building a housing project in their district or--worse yet--their own neighborhood, and their true colors shine through.

"In Santa Cruz, we have NIMBYism and exclusivity, hiding behind a mantle of environmentalism," says Mark Primack, a local architect and former member of the Santa Cruz Zoning Board.

Some bureaucrats and local developers blame poor planning--disguised as slow-growth and save-the-open-space politics--for the housing crisis. On the other hand, while they will tell you where and how to dig a hole in the ground, most are content to take the easy road, wringing their hands and passing the buck over the hill and further, to Sacramento and to Washington. Indeed, it's easy to argue that we will never fully meet the demand for low-income housing. But that doesn't answer the question at the crux of the housing shortage: What will the Santa Cruz community look like in 10 years if we continue to look the other way?

The War Is Over

IT'S A SAD STATE OF AFFAIRS when the soldiers on the front lines say we may already have lost the battle.

"We will never meet the need for low-income housing in Santa Cruz," says Elizabeth Vogel, associate director of housing development at Mercy Charities Housing, a statewide nonprofit group that develops low- and very-low-income housing. This isn't to say she's giving up, but she can't ignore a few elephant-sized roadblocks that prevent Mercy from taking to the streets, shovels in hand.

"Funding, and community and political support, stand in the way, along with some dirty little stereotypes surrounding 'low-income' people," Vogel says.

Watsonville City Councilmember Rafael Lopez is all too familiar with the problem. These stereotypes are perhaps most pronounced in Watsonville, which houses more than its share of low-income residents. The average income in Watsonville is $20,000--"very low income" by county standards.

"Affordable housing brings certain buzzwords with it: poor, crime, violence. And it shouldn't," Lopez says. "Affordable housing is about people who want safe homes and affordable places to live. When you're talking about affordable housing, it's not only the poor anymore."

The question of affordability is a slippery one because, by some measures, Santa Cruz's low-income residents would be fairly well off by comparison with the cost-of-living standards in other communities.

According to numbers from the California Department of Housing and Community Development, "low income" in Santa Cruz County is any single person making an annual income of $33,450 or less. The annual low-income salary for two people is $38,250, and a nuclear low-income family (dad, mom, two kids and a dog) earn $47,800. The statistics represent Santa Cruz artists, teachers, bus drivers, retail workers and coffeehouse barristas--basically anyone in a service-related profession. Minimum wage just doesn't cut it anymore.

Meanwhile, rising demand in both the rental and for-sale markets pushes up rents.

In the city of Santa Cruz, the vacancy rate on rental units is less than two percent. The low vacancy rates, combined with closed waiting lists for public housing assistance, mean fewer and fewer longtime residents can afford to stay here.

Realtor Tom Brezsny calls it "growth by default."

"It's when [officials] refuse to sit down and plan for growth, they just deny it," Brezsny says. "In turn, our housing prices will continue to go up and up as long as they hold the supply down."

"We're moving towards a swing where this county is going to be comprised of only very wealthy people," Primack adds. "I moved here in 1971 with $50 in my pocket and spent a lot of time getting established. I lived here and worked for minimum wage. I want it to be possible for people to still do that. I don't want this to be a gated community."

Glass Houses

FOR ALL THE LIP SERVICE public officials pay to building houses and rentals that the average person can afford, a lot of red tape must be plowed through before building a low-income rental.

"There are no incentives [to build rental units]," says architect Tom Rahe. "If the county wanted to see low-income rentals built, they could reduce building fees or encourage high density. They could build in incentives."

The Santa Cruz city building code says that so-called granny units, or accessory dwelling units, "are allowed because they can contribute needed housing to the community's needed stock." But first, the developer must have the Zoning Board's blessing (a.k.a. the design review) and pay a $450 design-permit fee, a $15 document fee, a $65 environmental-review fee, a $65 public-notice fee and a use-permit fee. The use-permit fee is $650 if the proposed home is one story and $1,220 if it is two stories or above a garage.

County fees also encourage building to sell. Building permit fees, including a school developer fee ($1,235), a sewer connection fee ($3,000) and a water connection fee ($3,000) are the same for a secondary rental unit or a house.

In the case of multiple rental units, the builder must pay separate fees for each unit.

"For a builder faced with 'Do I build a rental project or do I build to sell?' it's really a no-brainer," says local architect Matthew Thompson. "It's far cheaper to build a mansion here than it is to build apartments that are affordable to regular folks."

And dwindling supplies of rentals make landlords very choosy about tenants. Working-poor families, like the Perez family, feel this crunch the hardest.

"It's hard enough finding rentals here, but with seven kids, a dog and a housing voucher, it's nearly impossible," says Diana Perez. Perez, her husband, José, the couple's five children and their two nephews live in a four-bedroom apartment on Mount Madonna Road.

The county offers Section 8 housing vouchers, a federal subsidy, to low-income families like the Perez family. With the voucher, the Housing Authority pays the difference between a predetermined "payment standard" and 30 percent of the household's adjusted income. This means the county paid $1,308 for the March rent, and the Perez family paid $301.

Often, subsidized units are of poor quality. Diana Perez says the house has a plumbing problem, fecal coliform pollution in the water, rotten floor boards and needs other repairs. Running water is a rarity. And yet the landlord is upping the monthly rent on May 1, from $1,609 to $2,000. The Perezes can't afford the increase, so they are house hunting again.

In a way, the Perez family is lucky. They are one of the 3,000 families who receive rental assistance from the Housing Authority. There are 6,000 more families still waiting.

"We are now interviewing families who placed their name on the Santa Cruz waiting list [on or before] December 1992," says a recorded message on the county's wait-list hotline.

And the problem is only getting worse.

Eight Is Enough: For Diana Perez and family, finding affordable housing is like trying to win the lottery.

The Market's Revenge

BY 2010, the county's population is expected to reach 309,206--an increase of some 60,000 over the latest figures. That number is expected to grow to 367,196 people by 2020, according to projections by the state Department of Finance.

Meanwhile, the only numbers not skyrocketing, it seems, are the minimum wage and the number of available housing units--especially for low-income rentals.

Subsidized housing stock across the country is rapidly dwindling, with thousands of low-income tenants suddenly faced with the prospect of paying market rates. During the 1980s, developers nationwide signed 20-year agreements with the federal government to create low-rent apartments, using low-interest federal loans under the federal Section 8 program. With those agreements now expiring and the economy booming, many landlords are choosing to leave the program and charge market-rate rents. By 2001, an estimated 25,000 low-rent apartments are expected to be converted to market rate in California.

As the median price of a house skyrockets locally, rentals are being pulled off the market and sold at top dollar. The houses are now occupied by new owners, forcing groups of students and even families to find new homes.

"It's the revenge of the free-market economy," says Santa Cruz City Councilmember Tim Fitzmaurice, a lifelong renter.

What are called "build-out" rates are another speed bump on the road to building more low-income housing. City planners say 95 percent of the residential land within the limits of Santa Cruz County's four cities is already built out. County Principal Planner Mark Deming estimates the rest of the county's buildable land is between 80 percent and 90 percent built out.

But Deming and several others say it's not the build out that's keeping low-income projects at bay. It's the supervisors themselves and their slow-growth politics, which limit funds and land for low-income housing.

In October 1999, the Board of Supervisors again failed to bring the county's housing policies into compliance with state regulations, voting 3-2 against a series of amendments that would have made the county eligible for about $2 million annually in state low-income housing grants.

The county's housing policy, called the housing element, must be approved by the state Department of Housing and Community Development before the county can qualify for various state and federal grants. It hasn't been certified since 1994.

The amendments include changes that would allow manufactured homes to be used as granny units and would exempt the main units from the permit allocation process when a second unit is developed at the same time. One of the more problematic changes, however, would exempt second units from affordability and occupancy requirements.

Supervisor Mardi Wormhoudt, who voted against the changes, said they would cede local control to the state and would not guarantee that more low-income housing would be built.

The board, however, has pledged support for an agreement to adopt a countywide plan that will increase affordable housing, especially for farm workers, if the state approves a new high school in Watsonville.

"The real issue is local control," Wormhoudt says. "A certified housing element does not mean we are guaranteed additional funding, nor does it mean we will meet the demand for housing. Look at Santa Clara County, where the housing element is certified. There are tons of people with more money than sense, and they still have an insatiable need for housing. And it is still cheaper to live here than it is to live there."

But those additional low-income housing funds couldn't hurt, argues Kathy Bernard, executive director of Pajaro Valley Housing Corp., a nonprofit housing company that develops low- and very-low-income housing.

"It's still money," Bernard says. "And those funds can be used to leverage other funds. The supervisors could make a determined effort to say we are really going to bite the bullet and make it happen."

Digging a Hole

PRIMACK SAYS HE DOESN'T see that happening anytime soon. He describes the local politicians' positions on low-income housing: "As long as I've got mine, to hell with the rest.

"The language, the rhetoric, is all about diversity, but the actions are all about exclusivity," Primack continues. "When push comes to shove, nobody is willing to see it happen in their back yard. That's why we have so many illegal granny units in the county--the demand is being met, but the system doesn't want to allow it to be met."

So where do we build? Everywhere, Primack says.

"Building is not a crime. I'm not saying we should build in the greenbelt, but why not everywhere else? And denser is better. The best place to get dense is downtown. The more the merrier."

Some even boldly suggest building on land currently zoned for agricultural use.

"The whole policy of not wanting to increase densities because that induces growth means there are some potentials that don't get taken advantage of," says Pajaro Valley Housing's Kathy Bernard. "There's this recognition of the need for additional housing, but at the same time we're trying to deal with maintaining agricultural land and open space. It seems to me that there's been a lot more emphasis put on that end of it."

Meanwhile, the county Planning Department has identified a handful of sites where new low-income housing could be developed, Deming says.

He lists sites near Watsonville and in Soquel, along with a county-owned plot of land in the Seascape Uplands area that is zoned for multi-unit housing. According to the county's Measure J ordinance, passed in 1978, at least 15 percent of units in a housing project with five or more new units must be affordable to low-income renters.

There's also a Housing Authority-owned plot of land in the Seacliff area of Aptos that is zoned for affordable housing. In addition, several small pieces along Seventh Avenue in Live Oak could hold about 92 units zoned for urban medium density, "and if you increased the density zoning, you could build more than that," Deming says.

And there's always the possibility of streamlining the planning process--axing building, sewer and water fees along with design reviews, which make rentals and multiple units more expensive to build than mini-mansions.

"Could we streamline the process? I suppose we could, but the reason that housing isn't being built here is political," Deming says. "There really isn't any support for multi-family dwelling by the Board of Supervisors or the neighborhoods."

Although Deming says the 1st and 2nd Supervisorial districts have the land and the services to accommodate low-income housing, 1st District supervisor Jan Beautz doesn't condone more building.

Beautz says her district, especially the Live Oak area, was overly targeted with affordable housing developments in the 1980s. "I do not support building more dense development in the First District," Beautz says.

Since she took office in 1988, Beautz has been less than friendly toward affordable housing. In fact, the 1994 county General Plan reduced Live Oak's capacity to hold dense housing. She says she's only voicing her constituents' wishes, which clearly have been against more dense development in her district.

No Vacancy

THE HISTORY of the O'Neil Ranch exemplifies how NIMBY reaction has shaped Beautz's position and is emblematic of countywide barriers to low-income housing.

In 1989, the County Redevelopment Agency bought the 96-acre O'Neil Ranch for $6 million. The agency decided to build a park and set aside some of the land for low-income housing. A battle over how to use the land ensued.

"Some of the community advocates got up at the hearing and said, 'I'm in support of low-income housing, but after hearing how strongly the neighbors feel. ... I can't in good conscience advocate this project because I think the residents [of the project] would be hated,'" says Tom Burns, administrator of the Redevelopment Agency.

Beautz fought for seven years to persuade two other supervisors to vote the low-income housing project off the site.

Last month, "Save Soquel" members and residents cheered as the county unveiled plans for a 26-acre park on the O'Neil Ranch land, which fronts Old San Jose Road and wraps around the Soquel High School campus. The low-income housing was gone.

The neighbors won that battle, but Santa Cruz County as a whole may be losing the war. The fight demonstrated to many that there was simply no political upside to pushing for low-income housing.

"There is not one person or group who has consistently advocated for low-income housing issues," Burns says. "That becomes one of the problems. The neighborhoods speak loudly, but the low-income folk aren't as organized. They are struggling to make ends meet to live in this community, working a couple of jobs to be able to afford to live here. They don't have time to go hang out at a hearing. So it becomes the silent majority."

Preliminary plans for an affordable-housing project in the Seacliff neighborhood of Aptos are already drawing sharp criticism from the surrounding residents.

One recent Sentinel letter-to-the-editor writer illustrated the not-in-my-back-yard attitude that has successfully stymied so many efforts to build low-income housing in the county.

"I sincerely hope you're not attracting low-income people to the [Seacliff] area. ... I am saddened that the county would consider putting low-income housing in such a beautiful location."

The poor, apparently, don't merit an ocean view--an attitude that would eliminate from consideration many of the county's citizens and much of its buildable property.

A few dozen area residents turned out at a December public meeting to protest the 35 affordable rental units the Housing Authority Plans to build. The three-acre parcel at McGregor and Searidge drives has been designated for affordable housing since 1983. Construction is still at least a year off, says Mary James, the county Housing Authority's executive director.

"When we say we rent to low-income people, these are real people," James says. "We rent to several receptionists, a bus driver, several teacher's assistants, bakers, a librarian--all the people that provide us services and teach our children. When people are saying these people shouldn't live in Seacliff, they are saying that people who already live there now don't deserve to live there."

Much of the problem of providing low-income or affordable housing is indeed attitudinal. In a sense, it goes to the heart of how we define community, whether it is a place where all the people who actually work in it can also afford to live in it.

"Our heads are buried deeper and deeper into the sand, as the problem gets larger and larger," Primack says. "I firmly believe we'll always get the community we deserve. And if that's a community that has to say goodbye to our wait staff, to our creative people and to surfers who perhaps deserve to be here more than anyone else--they can't very well surf in Iowa--if we have to abandon all those fringe cultures that make Santa Cruz what it is, so be it. We're the Silicon Coast."

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

No Room at the Inn: The politics of exclusivity and slow growth are not keeping Silicon Valleyites out of the county--but they are making it difficult for longtime residents to stay.

Photograph by George Sakkestad

From the March 22-29, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.