![[MetroActive Movies]](/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Ramblin' Man

Santa Cruz filmmaker Aiyana Elliott tries to grasp the quicksilver life of her father, folksinger Ramblin' Jack Elliott

By Richard von Busack

YOU DON'T HAVE to be the daughter of a wandering folksinger to feel kinship with Aiyana Elliott, director of the documentary The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack. The filmmaker, who grew up in Santa Cruz, won the Special Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival with this study of her world-famous and mostly absentee father, folk musician Ramblin' Jack Elliott.

Mainly, the documentary tells the story of Elliott, who is still living and thriving at nearly 70 years of age. The other focus is Aiyana's attempt to get some information--she wants to learn about her early years and the breakup of Elliott's marriage to her mother.

Carrying out the second task is like trying to nail quicksilver to a wall. The elder Elliott twists and turns to avoid his daughter's questions, placing the blame for the breakup of his fourth marriage on Aiyana's mother, Martha, who left him for another man while he was on tour. ("That man moved into my territory" is the way Elliott puts it.)

Other times, he does his mighty best to change the subject. As Kris Kristofferson suggests, Ramblin' Jack may have gotten his name from his conversational style, as well as from being a well-traveled fellow.

"Your dad isn't that good at paying one-on-one attention," says Martha Elliott. Though The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack was made by his daughter--a loving daughter, let's stress that--Ramblin' Jack Elliott faces her questions with all the caution of a man being grilled on 60 Minutes.

THE FILM shuttles smoothly back and forth from present-day honors for Elliott to the musician's youth. He was born in the early 1930s as Elliott Charles Adnopoz, the son of a Brooklyn Jewish doctor and a loveless mother. (No one has a good word to say about Elliott's mother, neither her sons nor her sister.) At 16, the boy ran away and joined Col. Jim Eskew Ranch Rodeo, starting a lifelong involvement with horses and the West.

On the road, Elliott learned how to play guitar. Hearing folk musician Woody Guthrie on the radio, Elliott decided to track the man down. Elliott became a friend, housemate and student, learning Guthrie's songs and playing techniques. Aiyana interviews Guthrie's children, both the well-known Arlo and Nora Guthrie, Woody's daughter. (It's strange that a monumental figure like Woody Guthrie, composer of "This Land Is Your Land" and hundreds of other folk standards, exists in living memory. The strangeness is compounded by seeing that Woody's daughter has a computer on her desk.)

Jack Elliott often learned from direct observation of Guthrie, rather than lessons. "You can steal whatever you want, but I ain't giving it away," Guthrie told him.

Elliott began playing at impromptu jam sessions on Sunday afternoons at Washington Square Park, where aspiring folk guitarists listened and learned. A later trip to England with his first wife, June Hammerstein, brought Elliott's flat-picking guitar style abroad. Elliott exposed England to the roots music that British rock stars would later smooth down and export to the American children of the 1960s.

Personal Directions: Aiyana Elliott talks about the

local connections behind

'The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack.'

RAMBLIN' JACK Elliott's place in folk music was assured long before he received the National Medal of Arts from President Clinton in 1998. That Elliott continues to tour and perform at the age of 70 is, as they say of remarriage, a triumph of love over experience. (Elliott himself has been married five times.)

Elliott's virtuoso guitar techniques influenced countless guitarists. And it's true that he was an important mentor for Bob Dylan. The young Dylan was such a disciple that they once billed him as "The Son of Ramblin' Jack" at Gerde's Folk City, the Greenwich Village nightclub that was to the folk revival what CBGB's was to punk. Elliott taught Dylan an enormous amount about playing and singing. Moreover, Elliott gave Dylan a personal example of how one could mutate one's identity from Jewish kid to Western rambler.

Elliott's an important man, and this film proves it, but The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack made it clear to me why he's never been one of my personal favorites as a musician. And it isn't Elliott's too-cool personality that I object to, that irascibility that makes him half-tease, half-taunt his filmmaking daughter from the stage. After all, it's been years since I was bothered by the unresolvable contradiction that Bob Dylan is both a sensitive genius and yet capable of snake-meanness.

When I was a kid, Joan Baez was like a plaster saint in our house. When we all saw D.A. Pennebaker's documentary Don't Look Back during its first run in 1966, and watched Dylan mocking Baez, I grew an antipathy that lasted for years--until I heard all of the man's records and started to understand how huge his talent was. Like Baez, Dylan had the willingness to use his music to explore his fears and jealousies, and he risked turning himself inside out with music. Compared to his pupil Dylan, Elliott is basically a fine song-stylist and revivalist.

Elliott can bring hidden depth to songs like "If I Were a Carpenter." Another contradiction: Tim Hardin's song is a lovely classic that's fit for Promise Keeper meetings, with the singer offering his woman a chance to "follow close behind me" instead of giving her a place by his side. When contrasted with the unadorned music of the likes of Elizabeth Cotton and the Carter Family, seen in The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack in excerpt, Elliott's performances seem all the more measured, guarded and stylized.

I carried a little sadness and confusion after seeing The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack, just as I had after seeing Steal This Movie, the recent biopic about Abbie Hoffman. This isn't due only to my own rocky relationship with my father, which continues in years of stalemate and silence.

And I'm not saying that Elliott should have stayed put. It's a lot to expect that someone could marry a man named Ramblin' Jack and tame him into an ideal husband and father. In the end, Aiyana's questions to her father really go unanswered.

What Aiyana Elliott is confronting in her film is the spirit of the times when she was born, in 1969. That spirit is, as time goes by, more and more difficult to convey on film. How can one explain 1969's certainty of imminent doom, of collapse, of revolution, of sweet ultraromanticism combined with the apocalyptic ruthlessness in the way the sexes sometimes treated each other?

The key to The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack is a scene in which Aiyana Elliott interviews folksinger Dave Van Ronk. Van Ronk, a contemporary of Elliott's, doesn't seem to have much empathy for her quest. Let me put it more bluntly: he all but tells her that if she wants sympathy, she can look in the dictionary.

What Van Ronk actually says is this: The world could have had another family man at the expense of one less Ramblin' Jack Elliott, and so matters turned out for the best, as far as he and the rest of the world are concerned.

The real conflict in The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack is shown in this moment, in the contradiction between two sets of values: the '60s and the '90s. Neither is able to comprehend the other.

The sanitized Steal This Movie tries to explain Hoffman by applying '90s values to a 1960s-style life. It explains his promiscuity as serial monogamy or the fault of predatory groupies. It parses Hoffman's relentless energy as the result of manic depression--and portrays him as essentially a family man who failed.

In The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack, Elliott, '60s kind of guy that he is, is seen from a modern, '90s perspective and asked about the links a daughter and father ought to have. It isn't just that Elliott doesn't want to understand his daughter's need for a father who would have been there for her, but that at a fundamental level, he can't understand what she wants, either.

But what makes The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack a loving film and not an angry one is the daughter's flexibility. Aiyana Elliott, at least, tries to see where her father is coming from and uses her film as an inquiry. Thus the daughter exposes herself emotionally in her art, in a way that her father rarely dared in his.

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

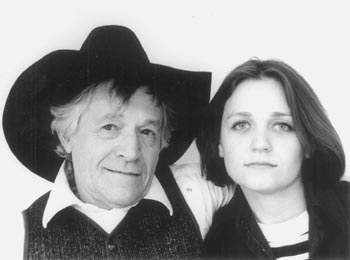

Family Folk: Aiyana Elliott stands by her man--and father--Ramblin' Jack Elliott.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

The Ballad of Ramblin' Jack Elliott (Unrated; 112 min.), a documentary by Aiyana Elliott, opens Thursday at the Nickelodeon in Santa Cruz.

From the August 30-September 6, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.