Stamp and Deliver

Your Pad or Mine? Kristine Imber is the lady behind the Rubber Stamp Lady.

Is it art or is it craft? When something's as fun as rubber stamping, does it matter?

By Kelly Luker

SOMEWHERE BETWEEN madness and ecstasy lies a rubber stamp with my name on it. Maybe not my name, exactly, but perhaps my initials. In calligraphy. Or maybe it's a stamp with a charming Holstein cow. But damn it, the perfect one's out there.

It's frightening to me--as well as to my friends and colleagues--that I've fallen into this parallel universe of rubber stamps, rainbows of ink pads and a library's worth of mail-order catalogs full of related paraphernalia. Using rubber stamps veers dangerously close to "crafts," a pastime that includes frilly ribbons, glue guns and a sick desire to crochet charming hats out of aluminum can fragments and yarn.

I always wanted to be the sensitive artist type--black beret, smoking Gauloises, bitterly resenting life's unfairness toward the gifted. However, it's hard to relate to the suffering of a Van Gogh or a Basquiat when your muse is a 3-inch rubberized image of Pooh.

The heat gun is what sealed the addiction.

Business took me near 41st Avenue, and with a few minutes to kill, I decided to check out a store named Rubber Stamp Lady. One could gather that this might be Ground Zero for those who like to ink and stamp. Who knew that the mere act of inking a Santa likeness and flattening it on a Christmas newsletter could support a whole store? Kristine Imber apparently did.

The lady behind the Rubber Stamp Lady, Imber began the store almost nine years ago out of her home. She was not around that fateful day I wandered in, but her assistant Cyndee Anthony was. It was Anthony who showed me how to get that cool raised effect on a stamped image. After stamping a picture, she sprinkled embossing powder over the wet ink, shook off the excess and fired up an industrial-strength heat gun. Within seconds, the powder crystallized, creating three-dimensional artistry.

It's what's called an epiphany, I believe, and within weeks I had dropped over $100 in inks, papers, embossing powders, a heat gun and, of course, the stamps: dragonflies, grape leaves, paw prints.

Perhaps the folks who have been inkin' and thinkin' about this for a few years could explain rubber madness. "We forget to play when we become adults," Imber says. "It's like kindergarten--you cut, color and paste." It also allows the brain to take a breather, Imber adds, while creating something appealing to look at.

BUT THERE is also a whole subculture within the rubber stamp culture that appreciates the rubber stamp as art. Just ask Marco Alpert. The Santa Cruz marketing executive recalls wandering into Beverly's Fabrics with his wife one day and being "vaguely intrigued" by the stamps he saw there. Less than a year later, one of his art pieces was included in Rubberstampmadness, the bimonthly magazine for rubber stamp enthusiasts.

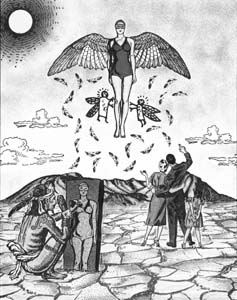

"I enjoy the surreal," Alpert says, "and rubber stamping lends itself to the surreal--the juxtaposition of images."

His piece Up, Up and Away involves 11 rubber stamps, as well as paints and masking. Because Alpert spends most of his time working in high-tech, he has set a self-imposed rule of staying "low-tech" with his artwork--no techniques that require electricity.

"In the stamping world, there's this dichotomy between 'cute' and 'weird,' " Alpert explains. That dichotomy probably helps answer the age-old question: rubber stamping--art or craft? Both, is the answer--and together they've helped put the rubber stamp industry into black ink to the tune of about $300 million, estimates Rubberstampmadness contributing editor Art Snyder. Snyder, who lives in Dayton, Ohio, has been working for the Corvallis, Oregon-based magazine for at least a dozen years.

"Rubber stamping used to be a cult," Snyder explains, "but now it's an industry." He says the roots of rubber stamping as an art could be found in the mail art movement, which allowed artists to exchange just about any artwork that could be stamped and shipped through the mail. Showing Dadaist influences, it encouraged the provocative to proclaim their work as art without fear of judge and jury. The movement percolated for about a decade and then took hold in the late '80s in Southern California with the formation of several rubber stamp companies.

Snyder acknowledges the dichotomy, but finds the terms "cute" and "weird" divisive.

"There's always that tendency to look down upon something as not 'true art,' " Snyder says. "Some of it is art and some of it is craft. Some people look at it as a leisure-time activity, but there are artists who look at it as one more tool in the art box.

"One of the appeals of rubber stamping," he continues, "is it allows any range of expertise--and non-expertise."

Snyder admits to owning about 3,000 stamps. Surprisingly, that's not an unusual number for the hardcore rubber addict. Kristine Imber estimates that about 20 percent of her customers own 3,000 stamps--or more.

BOTH SNYDER and Alpert, however, are in the minority. Snyder figures that men make up somewhere between 5 and 15 percent of the stamp world. Like Alpert, Snyder fell into his hobby/profession by accident. A radio announcer at one time, he ordered some rubber stamps to give away as gag gifts. Then he made the mistake of stamping one.

His passion led to a gig with RSM, which now consumes about 50 to 60 hours of his week between editing, reviewing catalogs and covering rubber stamp conventions--of which there are dozens--around the country.

With those kind of hours, does he ever find time to rubber stamp anymore?

Oh, yes. "Sometimes I'm on deadline and I'll say 'to heck with this,' and I'll go stamp something," admits the rebellious rubber editor.

While some naysayers have predicted the rubber stamp's demise, Snyder wouldn't snap the lid shut on the ink pads just yet. While he agrees that the market on the West Coast has probably matured, he sees a huge growth in the rest of the country, Canada and particularly Australia.

Roberta Sperling, publisher of RSM, says that her magazine was a quarterly with about 20 pages when it started. It now runs 164 pages with a circulation of 25,000. Sperling, who goes by the pen name "Rubberta," figures there are now about 500 rubber stamp stores around the country.

"We have people send in amazing work," Sperling says. "These are people who always had artistic talent but couldn't draw."

That probably would best describe Santa Cruz artist Jennifer Shoup. "I couldn't draw to save my life, but I always wanted to be an artist," says Shoup, who works part time at Rubber Stamp Lady. She shows a portfolio of pieces that integrate stamps, watercolors and layering techniques that evoke playful images of women. Rubber stampers tend to have a dominant theme they look for in stamps, and Shoup's is "flying ladies."

Not everyone will create pieces like Alpert's and Shoup's, but most everyone who picks up a stamp will be hard-pressed (sorry) to be disappointed.

"I can do something in two minutes and it doesn't look like two minutes," Imber explains. And it's true--there's a certain kick in knowing that a one-fisted motion can bring about a perfect drawing. Purists may pooh-pooh the craftlike aspects of merely filling color in between the lines, but the world of embellishments has gone far, far beyond that.

Imber takes me around the store, pointing out dozens of different paints and colored pencils, beads, lacquers, appliqués, chalks, metals and even leather that can be worked into the design.

"The craft is headed toward embellishments," Imber admits. "I've sold more accessories than stamps in the last two years."

Stamping also intersects with scrapbook making, the latest rage in crafting. Because both crafts use many of the same materials, it is a natural crossover.

Jennifer Shoup points out that stamping often opens the doors to other crafts. Because the need to display is almost as great as the need to create, stampers look for vehicles for their expression. Often it's through greeting cards, but Shoup has taken to creating homemade oils, lotions and bath salts for gifts that will also carry her stamp art on them.

Indeed, the vast network of Luker friends and relatives will be gifted this holiday season with homemade jam, complete with labels stamped to within an inch of their lives.

For someone whose art experience is limited to paint-by-number sets in childhood, there is a certain thrill in the immediacy of creating something recognizable and even somewhat attractive. Admittedly, the terror of morphing into the stereotypical crafter--large in the beam with an unhealthy attachment to way too many cats--has still not completely abated. But when my own deadline is looming, there's no denying the soothing repetition of ink-and-mash, ink-and-mash.

Which reminds me, I gotta go stamp now.

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Sakkestad Stamping His Style: Stamp artist Marco Alpert stays low-tech with his 'Up, Up and Away,' featuring 11 distinct stamps.

Stamping His Style: Stamp artist Marco Alpert stays low-tech with his 'Up, Up and Away,' featuring 11 distinct stamps.

From the November 12-18, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)