home | metro santa cruz index | film review

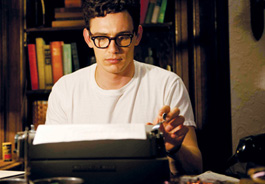

FREE VERSIFIER: James Franco's Allen Ginsberg works on 'Howl.'

Beat the Clock

The new film 'Howl' half-succeeds in showing how Allen Ginsberg's great poem withstood the censors

By Richard von Busack

I HAVE SEEN the best minds of my generation being used as fodder for well-intentioned movies that didn't quite make it. I wasn't a co-generationist with Allen Ginsberg, mind you; all we shared was a 30-second conversation in San Jose.

He told me, re David Cronenberg's Naked Lunch, "The movie didn't ruin the book; the book is still on the shelf. Next customer in line!" Or words to that effect.

As Ginsberg could have predicted, Howl the movie hardly ruins "Howl" the poem. As directed by frequent documentary makers Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, this is a film in four methods, beginning with a re-creation of "Howl"'s first reading 55 years ago in October in San Francisco.

Palo Alto's own James Franco plays the poet. His air of wounded sincerity and heavyweight sensitivity, so overbearing in full-length roles, is just right in these episodes. We see Franco's Ginsberg in a cramped apartment, sometime in the early 1960s; the scene is an interview about the work and a life ringed with madness. By "madness" one includes Ginsberg's own gayness; at that time, this was still treated as a mental illness by the psychiatric community, dealt with by institutionalization, electroshock therapy or jail.

These fictional interview scenes work well. They distill the poet's conversation and sum up the events of his life, and it's all low-key—unlike the usual scenes of a great man being grilled, forced to confront his paradoxes and demons. The sequences sums up the important relationships, the love affairs with Peter Orlovsky and Neal Cassady, as well as that passionate friendship with Jack Kerouac, which helped ease Kerouac out of the confines of his head and get him into a more physical kind of writing.

Howl's weakest part is the animation that illustrates the poem itself. Eric Drooker's design shows us towers of Expressionist cities giving way to heavenly visions and exalted genitalia. As when watching Fantasia, I was waiting for the monster to dispel all the flowing angels. Moloch looks like a giant Minotaur in this version.

Drooker's vision of the all-devouring symbol of America at its worst can't replace the other cinematic visions of the world-destroyer: the hallucination scenes in Metropolis and the earlier silent Cabiria, for starters. Ginsberg himself sourced his Moloch in different visual manners: at various times, he claimed he saw the false God depicted in the woodcuts of protographic novelist Lynd Ward's Wild Pilgrimage (1932) or in the form of a colossal phantasmagorical neon head of Sir Francis Drake that used to rotate above the San Francisco hotel of the same name.

Interspersed with the animated poem and the Ginsberg interview are scenes of the 1957 obscenity trial of the published poem, the People v. Ferlinghetti. It's startlingly undramatic stuff, and not just because we know the outcome. While every actor loves to play a villain, who wants to put any heart into playing a censor?

Cable TV all-stars take up the scenes: Jon Hamm, in a beautifully cut suit, radiates humanity as the defense lawyer Jake Ehrlich. David Strathairn gives his best weaned-on-a-dill-pickle mannerisms as a book banner, and Mary-Louise Parker bungees in as a witness for the prosecution.

Poet Ron Silliman's blog notes that the trial could have even looked even more patronizing than it does here; the real-life judge Clayton Horn in the case, played here by Bob Balaban, was a Sunday school teacher who used to sentence criminals to a viewing of the film The Ten Commandments.

At its worst, Howl pats the audience on the back. It assures them they would have been advanced enough to know this was a classic being talked about as if it were common porn. Ultimately, one is grateful for Epstein and Friedman's articulation of the poem. You can tell Howl the film will be doing duty as Cliff's Notes in literature classes for the foreseeable future. It's no substitute for reading it, even though one guesses students will be trying this substitute for years to come.

HOWL

(Unrated; 90 min.), directed by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman and starring James Franco, opens Friday at the Nickelodeon.

Send letters to the editor here.

|

|

|

|

|

|