Pinball Wizard

Whether the Beach Area plan will benefit the community is an open question--but it certainly is going to benefit Seaside Company owner Charles Canfield

By Eric Johnson

CHARLES CANFIELD IS grinning like a teenager showing off his hotrod. Standing in the lounge at the Surf Bowl nursing a Lighthouse Lager, he looks out over the lanes, where hundreds of his young employees are gathered for a monthly Seaside Company staff party. Strobe-lights flash and music pounds, punctuated by the crash of pins.

Canfield has just finished explaining how he came to own the Surf Bowl and is now bragging up his staff for rigging the discolike "Atomic Bowling" atmosphere on the cheap. He mentioned that since he took ownership, the Surf Bowl has increased revenue dramatically.

"The next thing I'm gonna do is build apartments upstairs, give these kids someplace nice to live," Canfield shouts above the racket. Diana Ligon, who manages the company's residential properties, rolls her eyes and laughs. Her boss, she explains, is just like a kid--darting from one project to another like a small-town capitalist pinball.

"I can't help it," Canfield shouts, shrugging and grinning, "I just love to build things!"

We've just come from his office across Beach Street, where Canfield spent two hours explaining his plans for the renovation of the Boardwalk and the revitalization of the Beach Area, describing his various business ventures and discussing politics. Maybe I just imagined it, but it seemed that throughout the interview, Ligon and PR specialist Ann Parker took turns kicking their boss under the table every time he said something politically incorrect. By the end of the interview, I figure he had a couple of badly bruised shins.

Even as he negotiates a huge deal with the progressive Santa Cruz City Council, Canfield is an unapologetic, shoot-from-the-hip conservative. One longtime political adversary, who says he has grown to kind of like the city's biggest land baron, nevertheless says he believes Canfield, 57, is "stuck in the 1950s. His brashness and rigidity seem like they were molded in the '50s, and so do his values and ideology," says the activist, who declined to be named. "Ultimately, he's one of those right-wing anti-government types."

Canfield earned his money the old-fashioned way--he inherited it. He also inherited a scrappy attitude and a rigorous work ethic from his father, Lawrence Canfield, who built the family fortune out of sweat and savvy.

Charles Canfield has known all his life that things would be easy for him, as long as he worked hard and didn't do anything stupid. And he appears to have little patience for what he sees as laziness or stupidity.

And Canfield does love to build things, and to buy and run things, too. In addition to the Boardwalk, his business interests range from the Marina Motor Company car dealership in Santa Cruz to San Diego's new municipal roller coaster (appropriately called the Giant Dipper) which he refurbished in 1989 and now manages.

He also owns as much as a third of the residential properties in the beach area--a number that has grown substantially in recent years.

Lately, Canfield's interests have branched further: He has taken a shine to rebuilding things. That has launched him into a new relationship with the city--one that he hopes will come to fruition with the passage of a plan that will allow him to dramatically expand his holdings at the Boardwalk.

It also has launched him onto center-stage in a hotly contested debate.

Business of Government

ABOUT FIVE YEARS AGO, Canfield bought the Beachview Apartments on Beach Street. Once a tourist hotel, the place had become a flea bag. Half the place was rented to low income people, who were forced to live alongside drug dealers and hookers, Canfield says.

"They were renting rooms by the hour," Ligon adds with a knowing glance.

Canfield believed the criminal element was hurting business at the Boardwalk, so he bought the place. He then contracted with the federal government to get Section 8 grants for full-time tenants, gave them temporary relocation money, and remodeled the facilities.

When tenants moved back into the refurbished building, their rents were less than they were before, according to SC City Councilmember Mike Rotkin. And Canfield still turned a profit.

Why, I ask, did a guy who's running a multi-million dollar entertainment empire as well as a half-dozen other projects, bother getting so deeply interested in such a rinky-dink deal?

"I think I wanted to show I could do a better job providing housing than the government could," Canfield says, and winces as though kicked.

Besides satisfying a healthy competitive urge, Canfield probably had another reason for showing that he could redevelop with the best of them. Andy Schiffrin, longtime member of the Planning Commission and now aide to SC County Supervisor Mardi Wormhoudt, says Canfield and company were demonstrating that they could navigate political waters that have experienced a tidal shift in the past couple of decades.

"When I first came to Santa Cruz in 1972, my impression was that the Seaside Company wanted to level Beach Flats and expand the commercial zone," Schiffrin says. "I think Charlie Canfield has realized that the political structure has changed, and that there is a deep commitment to providing affordable housing. This was an effort to show some good-faith."

Over the past couple of years, Canfield and the Seaside Company have become involved with several other small housing-renovation deals that involved some sort of public-private partnership. All of them began when Canfield became fascinated with some project and ended up making his company money. And that has led him to welcome the opportunity to work with the city to finalize the Beach and South of Laurel Comprehensive Area Plan.

As it happens, Canfield's newborn interest in teaming up with government coincided with the city's post-earthquake attitude. In the wake of the devastation of the earthquake, hobbled by Proposition 13, the city's progressive leaders--once belligerent toward business--evolved a strategy of cooperation.

The Beach Area plan was the city's idea. It was hatched to solve two problems--the deterioration of the neighborhoods it encompasses, and the city's dried-up coffers.

Councilmember Mike Rotkin, who has had dealings with Canfield since first coming to the SC City Council 20 years ago (mostly unpleasant dealings, by both men's admission), has been deeply involved in the negotiations with Seaside. Rotkin says the city had good reason to try to mend fences with its former nemesis.

"We felt a need to get some work done down there [in the Beach Area], and we recognized that without Canfield's cooperation, we might as well just hang it all up," Rotkin says.

Canfield possesses two things the city wants. One: He's got La Bahia. Two: He's got money. The SC City Council wanted access to both to solve its two pressing problems.

Trading Influence

HAVING FOUGHT OFF a conference hotel at Lighthouse Field, the City Council nevertheless recognized that year-round tourists would be good for the city's bottom line. And the funky hotel on Beach Street was unlikely to inspire a citizens' group to rally for its preservation. In La Bahia, the councilmembers saw a facility located at the beach and close to Downtown that could support convention-sized crowds.

Canfield did not want to do the actual development of the hotel--he had tried to run the Holiday Inn here several years ago and bombed. (In the bar at the Surf Bowl, he laughed when he said he lost more than a million dollars in that deal.) But the fact that he didn't want to run the place wasn't a deal-breaker. Canfield said he'd be satisfied to sell La Bahia to a real hotel company if the city would OK the plan--and if the city would allow him to expand the Boardwalk.

That was a little bit stickier, because it meant re-routing Third Street to allow the Seaside Company to consolidate its properties and free up a patch of ground for new rides. And that would mean tearing down 23 homes--half of which Canfield already owns, and the other half of which he's trying to acquire.

Still, the city found its way clear to thumbs-up that idea.

In return, Canfield agreed, tentatively, to cough up some money for the "public good." That lined up nicely with the City Council's and former Mayor Scott Kennedy's desire to build affordable housing in the neighborhood--an expensive project that the city cannot afford.

But there was a problem. Canfield had one bone in his craw that prevented him from completely giving himself to the new relationship.

In 1986, the city passed a tax on vending machines. In theory, it applied city-wide. In reality, the only person paying the tax was Canfield, because his machines were the only ones in town that could be monitored. It cost the Boardwalk $90,000 a year, a relative pittance compared to the $1 million-plus in taxes Seaside Company pays--but Canfield hated it on principle.

Canfield says he approached Kennedy in 1996 and threw down: Get me out of this situation, and I'll make it up to the city in other ways.

The City Council conceded, and the tax was rescinded last year. Some citizens howled, but Rotkin insists the council gave up the targeted tax because "it just wasn't fair."

Canfield says he took the money he saved from the tax reduction and invested it in the Surf Bowl. And he says that because the investment is paying off in increased profits at the bowling alley, his taxes to the city have almost returned to what they were before the tax reduction. That, Canfield says, is how city government ought to work. "If what you want to do is maximize the return to the community, then you allow government to be entrepreneurially driven. If I can make a profit and reinvest it--and I'll go at risk to make improvements--then payrolls rise and tax rolls rise. If you tie business's hands, then it'll wither and die."

Charles Canfield clearly loves this stuff. He describes the challenges and strategies of business like he was talking about an intriguing game. When he was still a kid, he took charge of the Boardwalk's gaming area. From the start, making money was fun. Now, making deals with politicians is part of the game.

Global Village

EVEN THOUGH HE OWNS a big chunk of it, Canfield does not consider Beach Flats to be a healthy community. "It is lacking in certain things that make up a community," he says. "I've seen a lot of changes in this town. There's more of a state of disrepair. Of course, the town was smaller, but there was also more pride of ownership. People maintained their yards. Today, people park their old cars out there."

His quaint analysis is clearly a conservative one. But a lot of people in Santa Cruz are finding it hard to trust this man's vision of the future. Canfield recognizes that he's hated in some parts of town, and faces this fact with a sardonic grin. "I'm little bit tired," he admits, "of getting beat up for trying to do something logical."

By "logical," Canfield means things that make business sense. He says he'd also like to help take care of the obvious problems: the area's high crime rate, the run-down converted vacation homes that absentee-landlords are allowing to fall apart, the dried-up lawns and broken-down cars.

But some critics feel that the Beach Area plan, as it has been presented for public consideration ignores what's good about the neighborhood that 1,200 people call home.

Andy Schiffrin says he is concerned that the whole Beach Area plan is skewed toward business interests rather than people. "It's very problematic that we're putting together a plan that provides most of the benefit to the Seaside Company and other developers," Schiffrin says. "'Revitalization' sounds really good, but the reality is it might mean a forced relocation of a large number of people. Some of these people haven't really bought into the idea of revitalizing their neighborhood."

Sandy Silver of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom says that, like Schiffrin, she feared that the redevelopment plan would mean bulldozing Beach Flats. She says she witnessed that brand of redevelopment 40 years ago when Dodger Stadium was built in Los Angeles. "There were a lot of poor people living in that neighborhood," she says. "They took out all those houses, and the people weren't relocated. I didn't want to see that happen here."

Schiffrin and others also say the current plan does not show enough concern for the Beach Area community. "I'm not sure that the plan differentiates between the drug dealers and the families who live there," he says.

The main problem stemming from this oversight, Schiffrin says, is that it shrinks the residential neighborhood, and does not seem to provide enough affordable housing. "The overall policies are good," he says, "but while the plan shows a significant net gain of housing, it is optimistic and unclear about how that will be done."

It is a fact that many residents of Beach Flats are undocumented workers, mainly men, who are here only to make enough money to send home to their families in Mexico. These residents sometimes chip in to share a place, then jam the place four-per-bedroom. After the plan is put into effect, such densities will not be permitted.

Silver says she hopes some provision will be made for the undocumented workers. "I know that the city's hands are tied by federal [housing] regulations, and that to get grant money you have to be a citizen," she says.

Bernice Belton of the Santa Cruz Action Network says it isn't just undocumented workers who will suffer. "I don't like the phrase 'affordable housing," Belton says, "because low-income people can't afford to live in 'affordable' housing."

Beyond the details, Silver says she hopes the political process is opened up. "We don't know what the quid pro quo is here," she says. "We don't know what trade-offs have been made. What are we giving up here and what are we getting?"

Whatever her criticism of the plan, Silver trusts its authors' intentions. "I think the city went into this with the idea of doing something positive for the neighborhood and for the economy, and making the best of a bad situation," she says. "The city definitely isn't a bad guy here, and I don't believe Charles Canfield is a bad guy, either."

Canfield, as crusty as he may sometimes appear, has no trouble breaking out with the community-spirited quote: "If people live in a really terrible environment," he says, "they develop no pride of place. That's not conducive to community. I think it's healthy that this community wants to change, and we want to help it with a commitment of resources and an investment of capital--plain old dollars."

Nevertheless, it's a safe bet that this investment will pay off in plain old dollars, too. Charles Canfield's self-interest may have become more or less enlightened in the past 20 years, but there's no doubt that he is playing this game to win.

[ Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

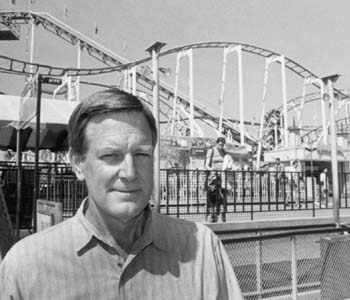

Falling Flats: Thanks to the SC City Council, Charles Canfield's Seaside Company stands to prosper when the Boardwalk expands into the nearby beachside neighborhood.

Falling Flats: Thanks to the SC City Council, Charles Canfield's Seaside Company stands to prosper when the Boardwalk expands into the nearby beachside neighborhood.

Chairman of the Boardwalk: Charles Canfield see his Seaside Company as a positive force working in partnership with the city to clean up the Beach Flats neighborhood.

From the May 7-13, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)