The young Hawaiian princes were in the water [yesterday], enjoying it hugely and giving interesting exhibitions of surf-board swimming as practiced in their native islands.

—Santa Cruz Daily Surf, Sunday, July 20, 1885

The story of the three Hawaiian princes surfing here in Santa Cruz in the mid-1880s has been woven into local lore. A plaque honoring the royal trio and their exploits in Santa Cruz has been erected at Lighthouse Point, overlooking the fabled surf spot Steamer Lane. A decade ago, the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History (MAH) staged an exhibit featuring two of the princes’ redwood surfboards (shaped here in Santa Cruz and buried in the basement of the Bishop Museum in Honolulu for decades) that proved to be the most attended show ever held at the local museum.

Now, there’s an even bigger historical set outside—and it will be breaking this week right here in Surf City.

Beginning at 7pm Friday and running into January 2026, the MAH will be hosting the largest surfing exhibit of its kind ever mounted anywhere in the world: Heʻe Nalu Santa Cruz.

The exhibit will feature more than 50 surfboards—many of which were produced by world-renown shaper Bob Pearson—including precise replicas of the two boards ridden by the princes here in Santa Cruz; the oldest known surfing artifact, a 16-foot, 240-pound wooden plank ridden in the 1830s by Hawaiian high chief Abner Paki (1808-1855); and a much more delicate board ridden by the Hawaiian princess Victoria Kaʻiulani (1875-1899).

The exhibit traces the history of surfing in Santa Cruz through the 20th century and features many contemporary boards designed by Pearson and ridden during the making of the Hollywood feature film Chasing Mavericks, which chronicled the life—and tragic death—of Santa Cruz surfing legend Jay Moriarty.

“I’m so passionate about surfing,” says an animated Pearson. “I made these boards to help tell the story of the beautiful Hawaiians who brought us the Sport of Kings, who made my life so much better and so much of my friends’ lives better. They brought us the surfing culture that is thriving. They brought us this, made us this. To be a part of it, I’m stoked! This entire story and the exhibit [at MAH] has us all just fired up, energy positive. Everybody is in this, and it’s family. Like the Hawaiians say, Ohana. Ohana. This is love, this is unreal.”

RIDING THE FIRST WAVES

Based on decades of research first presented in Good Times more than a dozen years ago and enhanced by several findings since, the exhibit chronicles the 140-year legacy of the princes’ seminal visit to Santa Cruz in the summer of 1885.

Of special note is a section featuring nine early Santa Cruz surf shops from the 1950s and ’60s—Yount, Haut, Scofield, Olson, Hobie, Freeline and Johnny Rice shops and, of course, Jack O’Neill’s original surf operation overlooking Cowell Beach, which has grown into an international institution.

Also of focus are four women who have played a seminal role in this legacy: Antoinette Swan, the true linchpin of the princes’ sojourn to Santa Cruz and who was a prominent figure in the ruling Hawaiian monarchy of King David Kalakaua and later, following his death, of Queen Esther Julia Kapiʻolani; the aforementioned princess Kaʻiulani; legendary swimmer and surfer Dorothy Becker, who lived much of her childhood in Santa Cruz and moved to Hawaii, where she became one of the first women from the mainland to surf Wakaiki; and Rosmari Rice, the lone woman on the Dewey Weber surf team of the 1950s and a surfing fixture (along with her late husband, Johnny) in Santa Cruz.

There will also be a wide-ranging series of lectures, surfing exhibitions (including many of the world’s greatest surfers), walks, films and even a short play, “There Are No Kooks in Heaven,” by Santa Cruz’s theatrical whiz Ian McCrae, the proprietor of Hula’s Island Grill. It is truly a community-wide event.

“We’re thrilled to share this exhibition with residents of Santa Cruz County but also with a larger regional and statewide community,” said MAH Deputy Director Marla Novo. “Our intent is to highlight this fascinating cultural legacy, make links to a broader conversation, and to honor our relationship with the water that began before the princes came to Santa Cruz. This isn’t the beginning or the end of the narrative. It continues in the ways we connect with each other, share and listen, one wave at a time.”

REDWOOD BOARDS

The seminal moment in this story took place on the Santa Cruz waterfront, during the mid-summer of 1885. In the early edition of the Surf on Monday, July 20, the newspaper carried lengthy accounts of all the previous weekend’s festivities on the Santa Cruz waterfront under a detailed column titled “Beach Breezes.”

The Surf reported that on no other Sunday of the season “have so many bathers, both ladies and gentlemen, been in the water, and all pronounced it delightful.” A small theatrical troupe, including a small donkey pulling a miniature cart, performed a comedy routine along the breakers and “afforded much merriment to the spectators.”

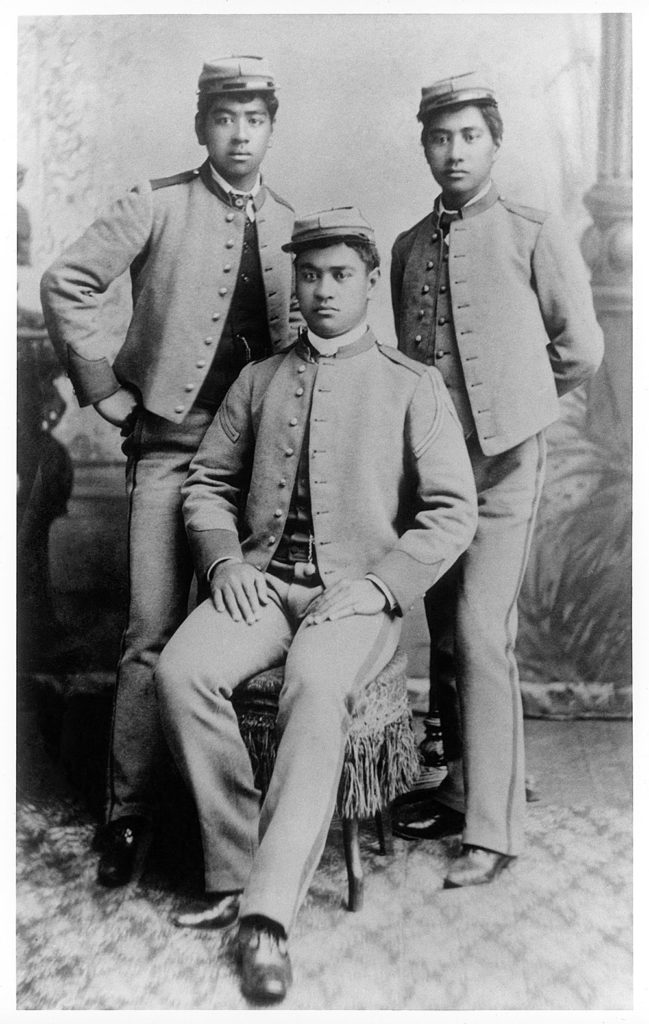

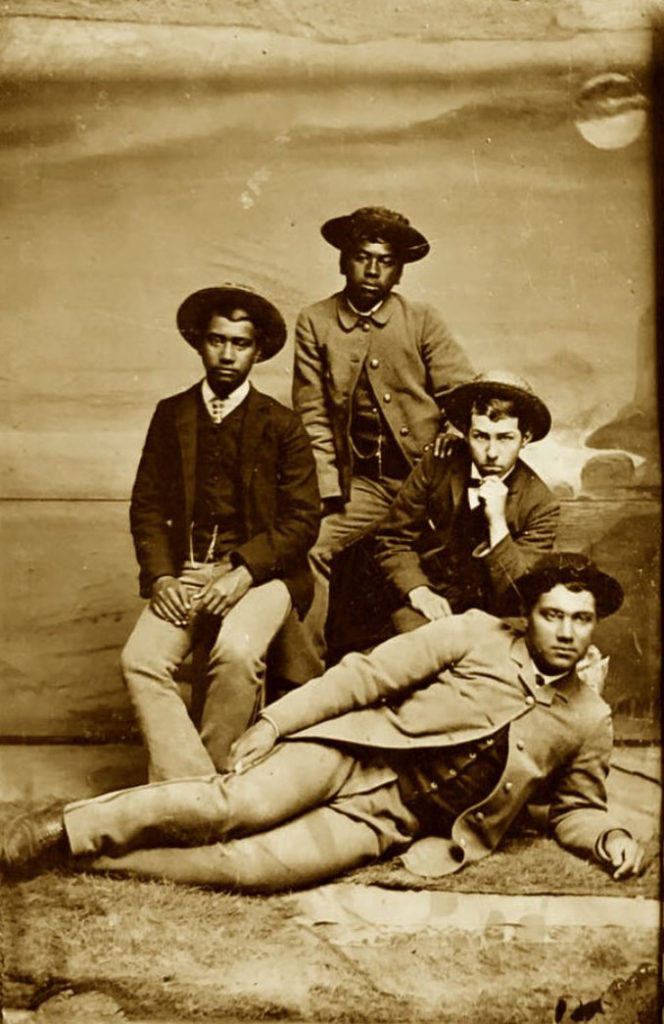

Further east along the beach, however, at the mouth of the San Lorenzo River, history was about to be made. The three Hawaiian princes—David (“Koa”) Kawananakoa, Edward Keliiahonui and Jonah Kuhio (“Cupid”) Kalaniana‘ole—were in the water with long surfboards made of local redwood, and milled in the shape of traditional Hawaiian o‘lo boards, reserved in the Islands traditionally for royalty.

According to the Surf, “The breakers at the mouth of the river were very fine and here occurred the very primest of fun, at least, so said those who were ‘in the swim.’” As many as 30 or 40 swimmers were out in the water with them, “dashing and tossing, and plunging through the breakers, going out only to be tossed back apparently at the will of the waves and making some nervous onlookers feel sure that they were about to be dashed against the rocks.”

And then came that fabled first account of surfing anywhere in the Americas: “exhibitions of surf-board swimming as practiced in their native islands.”

What is significant to note in all of the waterfront descriptions appearing in the local newspapers that summer is that there were numerous accounts of both local and visitors alike engaging the surf and ocean in a multitude of sporting activities: swimming, body surfing (playing in the waves), diving and simply wading. The “surf zone”—referred to in Hawaiian as ka po‘ina nalu and viewed as critical to the islands’ history—had already been claimed for athletic activity long before the princes’ arrival.

CHIEFESS

The three princes were not some casual day-trip visitors to Santa Cruz. And the family they stayed with here—Lyman and Antoinette Swan—also had complex links to Hawaiian history and, in the case of Antoinette Swan, direct lineage to royal Hawaiian bloodlines.

Twenty years after the princes arrived in Santa Cruz, an obituary appeared in the Surf on Oct. 2, 1905, for “Mrs. Antoinette Don Paul Marie Swan,” who had died the day before at her family home on Cathcart Street. The obituary noted that Swan “was courtly in manner, and had a charm in her dealing with people that won many friends. She was a kind neighbor and a devoted mother, loved by her children.” She was clearly a well-liked and widely respected member of the community.

The obituary also included some detailed information about Antoinette’s lineage, rather unique to Santa Cruz at this time:

She was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, of Spanish parentage on her father’s side, he being for many years consul from Spain at Honolulu, and owner of the island at the mouth of the Pearl River, and was very prominent in the islands.…Her mother was of Scottish and Hawaiian ancestry. She married Lyman Swan in the islands, and they came to California in 1846, and, about 12 years after their arrival came to Santa Cruz, where she has since resided, except for a number of years spent at the islands, where she dwelt with the royalty at the palace, being a member of the King’s household, as she was secretary to [the] Queen, wife of King Kalakau [sic].

Not all of the information in the Surf obituary is accurate, but it is close enough to provide both an open window into her life story and enough clues to put the various pieces of this intricate historic puzzle back together.

According to baptismal records in Hawaii and her death certificate here in Santa Cruz, Antoinette “Akoni” Marin was born on the island of Oahu on October 6, 1832. Contrary to the reference in the obituary, her mother, Kaikuloa, was a full-blooded Hawaiian and a “chiefess,” which made Antoinette, by birth, of ali‘i or noble Hawaiian lineage.

Her father, Don Francisco de Paula Marin, was a legendary figure in Hawaiian history, from his first arrival in the islands in the early 1790s until his death in Honolulu in 1837. While he was never “consul from Spain,” as would later be claimed (indeed he deserted the Spanish army), he served in the role of unofficial consigliere to Kings Kamehameha III & IV and played a major role as liaison between European and American vessels and native Hawaiian authorities.

Records clearly indicate that Marin was a polygamist in Hawaii. In one fascinating letter sent to Marin from Monterey in 1823 by Luis Antonio Arguello, the first governor of Alta California under Mexican rule, Arguello suggests that Marin had expressed interest in relocating to the California coast. “As to settling in this province, you alone could very well do it,” Arguello intones, “but by no means can I approve of your bringing four wives that are not legitimate, as I am informed that you have, and consequently some twenty children of theirs.”

By the time Marin had died in 1837, he had fathered, according to various accounts, as many as 27 different children. His last daughter, Antoinette, had just reached her fifth birthday.

HANAI RELATIONSHIPS

Following Marin’s death, Antoinette was adopted by Dr. Thomas Charles Byde Rooke, a prominent British physician who had also married into an ali‘i family.

It’s hard for foreigners to fully grasp the significance of “hanai” (adopted) relationships in Hawaiian culture. Western traditions of genealogy simply do not translate. But a hanai relationship is very much equal to blood lineage. In her autobiography, Queen Liliuokalani offered that hanai “is not easy to explain to those alien to our national life, but it seems perfectly natural to us.”

In November of 1851, an item in the Honolulu Polynesian newspaper noted that Antoinette had married Lyman Swan, then a young businessman on the Honolulu waterfront. He was a partner in Swan & Clifford, a seemingly successful chandlery business that fitted out whaling ships during the heyday of the Pacific whaling industry.

In April of 1853, Antoinette gave birth to the couple’s first child, Olivia (“Lily”), and the young Swan family appeared to be living a life of prosperity and promise in Honolulu. But as often would be the case with Lyman Swan throughout his life, appearances were often deceiving.

Apparently, unbeknownst to his partner, Ornan Clifford, Swan began forging “bills of exchange” (or checks) with several whaling ships. On April 13, 1855, authorities in Hawaii issued a detailed circular (akin to a wanted poster) charging both Swan and Clifford with forging $40,000 in promissory notes and leaving more than $80,000 in unpaid bills just after Swan had snuck out of Honolulu in March of 1854. It was a huge amount of money during that era—the equivalent of more than $10 million today—and the case quickly garnered international attention. A $5,000 reward was offered for information about their whereabouts.

While Clifford immediately returned to Honolulu and declared his innocence, Swan was apprehended in Alameda, California. All of the forged bills, it turned out, had been executed in his handwriting. While Hawaiian authorities tried to extradite Swan, he was never to return to the islands again.

Somehow, during his various court cases, Swan managed to bring Antoinette and his daughter Lily to California, where the family first resided in San Jose, and then moved to Santa Cruz in the mid-1860s. By that time, there were four more children in the Swan household.

The family opened a bakery on Pacific Avenue and purchased a large plot of land in downtown Santa Cruz, at what is now the corner of Front and Cathcart streets, that backed up to the San Lorenzo River.

LIFE ROPES

In 1884, the popular Hawaiian monarchs, King David Kalakaua and his wife, Queen Consort Esther Julia Kapiʻolani, who were childless, adopted the three princes after the deaths of their parents. By blood, the three brothers were Kapiʻolani’s nephews, the sons of ali‘i from Kauai, and they had been sent to Hawaii’s finest schools. Now they were being prepped for the monarchy.

David, the oldest (and nicknamed “Koa”), was born in 1868. Strong and handsome, at the age of 16, in the fall of 1884, he was first sent to St. Matthew’s Hall, a full-fledged military school for boys, located in San Mateo. The following year, Edward, born in 1870 and the frailest of the three brothers; and Jonah, nicknamed “Cupid,” born in 1871 and a brilliant athlete in all sports, joined their elder brother in California.

When not at St. Matthew’s, the three princes were placed under the careful eye of Antoinette Swan in Santa Cruz. The recently completed railroad line made their commute from school to the seaside resort an easy one.

The location of the Swan family home is of significant geographical import to this story. Up until the construction of the San Lorenzo River levees by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1955, the banks of the San Lorenzo River were woven into the fabric of life in downtown Santa Cruz. Boating, canoeing, swimming, fishing and strolling in the riparian corridor were all common daily practices.

The rivermouth itself had long been a popular location for “surf-bathing” activity on the Santa Cruz waterfront. As early as the 1860s, “life ropes” or “swim lines” (thick ropes attached at the beach by tall poles and extending out to floating rafts or anchors beyond the surf break) had been established at various points along both the main beach and Seabright Beach east of the river.

According to records kept by the waterfront historian Warren “Skip” Littlefield (1906-1985), the princes rode surfboards made of “solid redwood planks and milled locally by the Grover Lumber Company.” The Swans’ proximity to the San Lorenzo would have made the transport of these heavy boards easily facilitated downstream to the river mouth.

TROOP TAKEOVER

In 1887, Edward was sent home ill from St. Matthews and died a short time later in Honolulu from scarlet fever. The two other princes, David and Jonah, would carve out significant niches for themselves in Hawaiian history. The eldest brother, David, would eventually become the immediate first heir to the throne. Youngest brother Jonah, who had been Queen Lili‘uokalani’s personal favorite, was second.

Neither of them, however, would ever become king.

In January of 1893, a group of American and European businessmen, aided by the U.S. military, overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy. Queen Lili‘uokalani was deposed on January 17, 1893, relinquishing her throne to “the superior military forces of the United States.” Two years later, then 24-year-old Jonah, a fierce advocate for Hawaiian independence, fought in a rebellion against the U.S.-supported republic and was sentenced to a year in prison.

It was while Kuhio was incarcerated that a short account of Santa Cruz waterfront activities appeared in the weekly edition of the Surf. “The boys who go in swimming at Seabright Beach,” the newspaper noted, “use surfboards to ride the breakers, like the Hawaiians.”

Like the Hawaiians. From 2,400 miles away, Kuhio no doubt had more significant matters on his mind, but his waterfront exhibition of a decade earlier had taken hold in the surf at Santa Cruz and would flourish there for decades to come.

In 1902, Kuhio emerged from prison and a subsequent exile to participate in Hawaiian politics. While his brother David headed up the state’s Democratic Party (and was a delegate to the 1900 Democratic National Convention), Jonah joined the Republican Party and was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1903 as a “delegate” from the Territory of Hawaii, where he served until his death in 1922.

The Museum of Art & History is located at 705 Front St in downtown Santa Cruz. For more info go to the website at santacruzmah.org. Or call 831-429-1964.

Heʻe nalu Santa Cruz

Museum of Art and History

Partial Schedule of Events

Princes of Surf

■ Opening Reception

Friday, July 18, 2025,

7-8 PM

at the MAH

■ Paddle Out at the Rivermouth

Saturday, July 19, 2025

10- 11:30 AM

Rivermouth, Main Beach 400 Beach St, Santa Cruz, CA 95060

■ Surfing Exhibition of Traditional Hawaiian Boards

Bob Perason & Friends

Cowell Beach

August/September

TBD (depending on tides and conditions)

■ Dorothy Becker Talk

Ed Guzman

Friday, September 5, 2025

6-7 PM

at the MAH

■ Heʻe nalu Santa Cruz Book Launch

Geoffrey Dunn & Kim Stoner

Friday, October 3, 2025

6-8 PM

at the MAH

■ Antoinette Swan Gravesite Tour

Geoffrey Dunn & Barney Langner

Saturday, October 4, 2025

11-12 PM

Santa Cruz Memorial Cemetery

■ Antoinette Swan and the Princes of Surf Walking Tour

Geoffrey Dunn & Kim Stoner

Saturday, October 11, 2025

11-1 PM

at the MAH

■ There Are No Kooks in Heaven:

A Play by Ian McRae

TBD

November/ December

at the MAH

What a wonderful article! So much history and really interesting. Kook or not, thank you.