It’s an amazing example of the power of the written word to shift perception and rewire the emotions: Picture yourself on the mighty Mississippi River, sometime in the mid-19th century. A boy and a man are making their way downriver with a canoe and a makeshift raft. Both are on the run. Knowing their names is not important. What’s important to the scene is this: Along the way they have found a collection of books, beautiful leather-bound classics, and the man at first sees them as treasures denied to him, like a castle beyond a locked gate. He has taught himself to read, but never been free to dive into a book, nor to let anyone see him doing so.

“I really wanted to read,” the man tells us on page 75 of the novel James by Percival Everett. “At that moment the power of reading made itself clear and real to me.” Picture this revelation coming out on the water, Illinois on one bank and Indiana on the other. “It was a completely private affair and completely free and, therefore, completely subversive. … I pulled my sack of books closer, reached in and touched one. I let my hand linger there, a flirtation of sorts.” Finally, he begins reading, and: “I was somewhere else.”

It’s hard to imagine a passage that more potently fulfills the spirit of the ambitious “Deep Read” program of the UC Santa Cruz Humanities Institute. Now in its sixth year, the program seems to have fully hit its stride by choosing Everett’s masterpiece James, a book in which an enslaved African American by the name of James comes fully to life and mocks—and deconstructs—Mark Twain’s characterization of “Jim” in the oft-assigned novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

For those who might have wondered if the Everett book was a mere stunt, shooting fish in a barrel in a way sure to please the current guardians of taste in American literature, this is a novel far too full of life and life knowledge and insight and a wicked sense of fun to be constrained by any such characterization. Everett is every bit the American original that Twain himself was.

Just as powerful is this passage: “For the first time in my life, I had paper and ink,” Everett writes as James. “I was beside myself. I found a straight stick and shaved it to a point and scratched a groove on one side. I put the paper on my lap, dipped my stick into the ink and wrote the alphabet. I printed letters as I had seen them in books, slowly, clumsily. Then I wrote my first words. I wanted to be certain that they were mine and not some I had read from a book in the judge’s library. I wrote: I am called Jim. I have yet to choose a name.”

And we, the reader, are pushed forward, as at the start of some powerful roller coaster that can smoothly accelerate us almost without us noticing. And as in Kurt Vonnegut or Toni Morrison or some early James Baldwin, Everett’s words have both a deceptive simplicity, an apparent lack of effect, and yet do the work of prose that labors far more demonstrably and does it better. Consider the words, “I wanted to be certain that they were mine and not some I had read from a book in the judge’s library.” For me at least, reading this novel in the context of a period in U.S. writing when so much is derivative and overtly pitched to the sensibilities of various gate keepers, the words ring like both a warning and a shot of encouragement to anyone daring to write: Be yourself, all the way, and don’t worry too much about what anyone thinks of you.

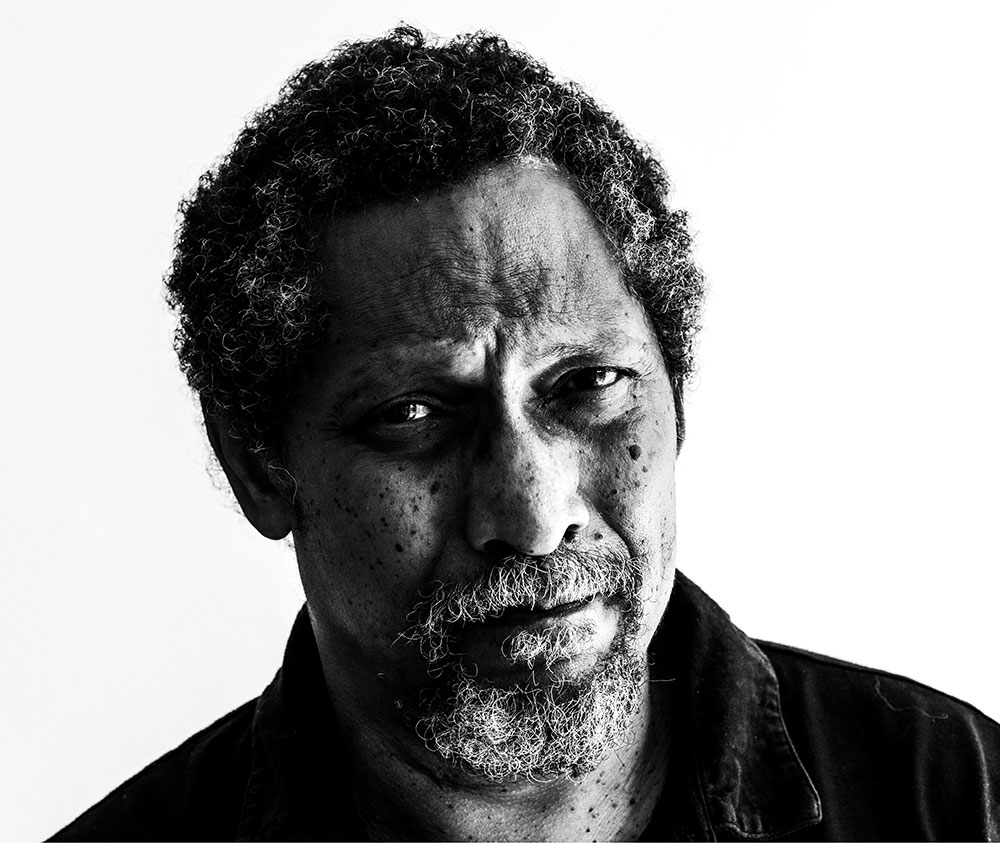

‘We are not a reading culture. Art makes us smarter, but it requires an effort on the part of the audience.’

—Percival Everett

The UCSC Deep Read program is a great idea, and this year it helps the Humanities Institute celebrate its 25th year. Ten thousand copies of the Everett novel were purchased and distributed to people in the community to read along together for a kind of group read. Most novels never sell 10,000 copies total; this program adds 10,000 in one stroke.

“Since I don’t go online for anything but email, I didn’t know about the program,” Everett said via email in an interview for this article. “It sounds wonderful. I’m thrilled to imagine my work reaching so many new readers.”

The program includes various warmup events, and a series of emails encouraging readers to dig deep into a thoughtful consideration of the text. Participation has climbed from 3,874 the first year (featured author: Margaret Atwood) to 6,135 in 2021 (Tommy Orange), to 7,035 in 2022 (Yaa Gyasi), to 8,544 in 2023 with Elizabeth Kolbert, then more than 9,500 a year ago for Hernan Diaz and more than 11,000 this year for Everett.

“We designed it from the very beginning to be a place for the community to gather and read together, but also to use this amazing resource we have in our community, the University of California, to be able to enter a work of art through various perspectives,” Irena Polić, a co-founder of the program, told me via email a year ago.

This month, she added: “I am amazed at how many people are reading with us today! When my colleague, Sean Keilen, and I were imagining this project six years ago, we were sure it was going to be popular, but what’s happening on the ground today surpassed our wildest dreams. The Deep Read consists of over 11,000 people in our community and all over the world, who are tuning in to weekly emails, showing up at events, and having a deep engagement with the book and the work of our institute.”

The various strands of the group-reading project culminate in a May 4 appearance by Everett at the Quarry Amphitheater for a 4pm conversation with Vilashini Cooppan, a UCSC literature professor. The event is free and open to the public and ought to be a lively, entertaining affair.

“We really wanted to choose a book that was trying to speak to issues that are fundamental to THI and to the Deep Read program—reading, writing, literacy, the importance of self-authored humanity and agency,” said Laura Martin, research program manager for the Deep Read program. “James is a book that tackles these issues head on, showing how James struggles to read and write himself into his full humanity and announce himself as a subject (‘I am James’) in a world of U.S. slavery that is set up to deny and prohibit his literacy, humanity, and freedom.”

Everett is a unique figure in American letters in a lot of ways. He’s published more than 20 short story collections and novels, many of them making a splash, and some ending up as film adaptions—notably, his novel Erasure was turned into the 2023 film American Fiction, starring Jeffrey Wright, and his second novel, Walk Me to the Distance, was adapted as the ABC-TV movie Follow Your Heart. Everett lives in Southern California and teaches at USC, where he’s a distinguished professor of English literature, but he also has a refreshing attitude about the publicity machine associated with publishing. Put simply, he can take it or leave it.

Asked about his 1983 novel, Suder, which explores what happens when a Seattle Mariners infielder in a bad slump simply flees, along with his LP of Charlie Parker’s Ornithology. “I don’t really think about my past work.”

OK, then… He does, however, explain: “I’ll watch people play anything. I’ll watch people throw darts. I have to say I don’t really follow baseball until October.”

He declined to answer a question about whether he has read Mario Vargas Llosa, the Peruvian novelist who died on April 13, but did share this general thought: “It is true that South America has a richer history of political fiction than we have. It’s a bit of an illusion. Often our politics are embedded in the work. Think of Little Big Man (Thomas Berger), If He Hollers Let Him Go (Chester Himes), Midnight Cowboy (James Leo Herlihy), Bluebeard (Vonnegut), Their Eyes Were Watching God (Zora Neale Hurston).”

The sense one gets interviewing Everett is that he wants to say: Read the books. Leave me alone. Asked to point toward answers to larger cultural problems arising from a read of his novel, he gives answers like, “If I knew, I’d tell everybody,” and “I wish I knew.” He seems allergic to pontification. Which might make him the perfect candidate for the “Deep Read” treatment.

Consider this fascinating riff on James from the “Deep Read” email conversation, exploring the novel with the help of UCSC literature professor Susan Gillman. “Everett is also drawing our attention to language as performance and, thus, depicting slavery itself in performative terms,” it reads. “Slave vernacular is a performance that James describes as linguistic expertise, as evidence of a ‘mastery of language’ and ‘fluency,’ and as a political necessity, required for ‘safe movement through the world.’ It is also ‘exhausting,’ as we see when James is traveling with Huck and is forced to ‘play’ the slave at every turn, occasionally having ‘language slips’ due to this exhaustion and perhaps his growing camaraderie with Huck as well.”

The “Deep Read” email lesson goes on to cite a powerful scene early in the book when James is trying to teach his daughter and other children: “They’re bright and eager, but they don’t yet understand why they have to learn this second language of enslavement. We see this in an exchange James has with his daughter: ‘Papa, why do we have to learn this?’ ‘White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them,’ I said. ‘The only ones who suffer when they are made to feel inferior is us. Perhaps I should say “when they don’t feel superior.” So, let’s pause to review some of the basics.’

“James’s lesson makes it clear: slave talk is a protective performance, a tool for survival in a violent slave system. When teaching the children how to warn a white neighbor about a fire, he instructs them not to say ‘Fire!’ but instead, ‘Lawdy, missum! Looky dere.’ As he explains: ‘We must let the whites be the one who name the trouble.’ While these language lessons reveal slave talk as strategy, they also depict a fundamental irony of the novel: only the enslaved characters know that they are performing the stereotypical language of enslavement. The white enslavers are ignorant of the doubled voices of the enslaved characters as well as the performative nature of language and, thus, slavery.”

Everett himself resists this kind of sweeping formulation. He wants to let the power of his story speak for itself, even if there might be obstacles to that, like the cacophony of our social-media-clogged, short-attention-span world. “I wish I had a remedy,” he says. “I suppose it is up to writers to find a way to compete with the popular formats. A bit of education would help, but we can see how valued education is in this culture.”

All a writer can really do is help to prod the imagination and leave it more supercharged than it was before. For Percival Everett, being a father has helped him see the world differently. “I’m more sentimental, I think,” he said. “I realize that I know less than I thought.”

Wise words to contemplate for anyone seeking to bask in the celebration of a great book. Everett reminds us to accept the limitations of the project of seeking to turn words on a page into a vehicle of higher meaning. “We are not a reading culture,” he said. “Art makes us smarter, but it requires an effort on the part of the audience. Education, education, education. More a desire to be educated for no other reason but to serve curiosity.”

UC Santa Cruz and its Humanities Institute are making that effort. Just what will emerge from that attempt may take years to know: What great writer of tomorrow might be launched by contact with Everett for this program? Who might be inspired and what will it mean? All good questions, just don’t expect Everett to pretend he has all the answers.

“That any work lives a while is great,” Everett adds. “People take from art what they need. I’m not smart enough to imagine that for anyone else. I’m certainly not smart enough to guess what my novel means. I am smart enough to know that I don’t know anything.”

For details, visit thi.ucsc.edu/deepread.