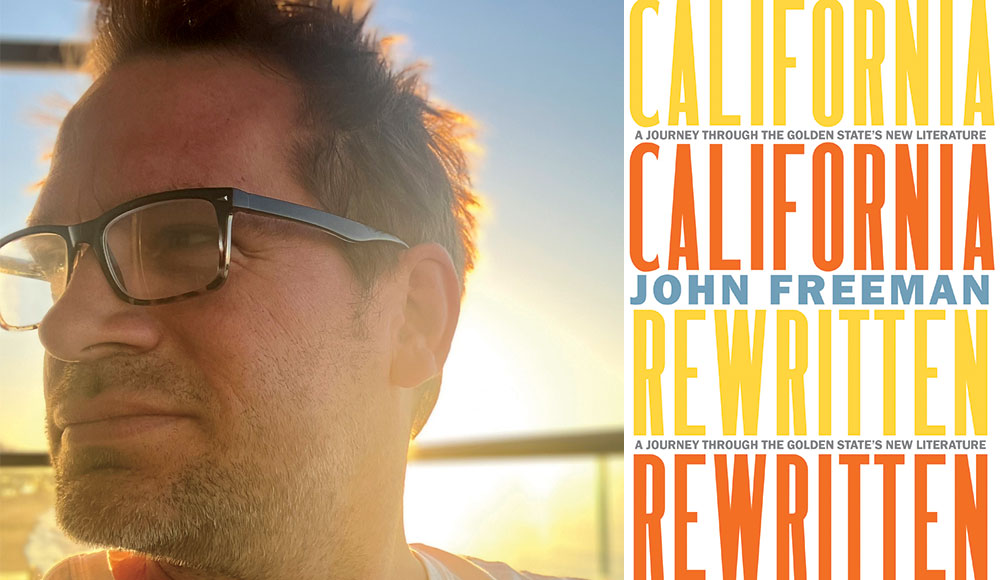

John Freeman, author of just-released , has an ask for his East Coast friends. “Picture the entire length of the East Coast as one state,” he says. That might give them an idea of the multi-habitat, multicultural, multi-political jigsaw puzzle that is California.

This concept is reflected in the 51 essays that make up California Rewritten, covering work from living California writers from Deborah A. Miranda (Bad Indians) to Amy Tan (The Backyard Bird Chronicles). Multiple Bay Area authors are part of the mix, including Rebecca Solnit (A Paradise Built in Hell), Elaine Castillo (America Is Not the Heart), Karen Tei Yamashita (I Hotel), Tommy Orange (There There) and Maxine Hong Kingston (The Woman Warrior) along with others.

The idea for the book first came up in 2019, when Freeman was having dinner in Berkeley with a group of people associated with his magazine, Freeman’s. It evolved as he hosted Zoom conversations with Alta Journal’s California Book Club. One of the first discussions kickstarting the idea was of C Pam Zhang’s How Much of These Hills Is Gold, Freeman said in a phone interview. The story about a Chinese family moving to California during the Gold Rush is “a story distorted by time,” he said.

In the essay on this book, he writes, “It might be a stretch to call it California’s Beloved, but [the writing] moves with the same rough magic and has a similar relationship to America’s radicalized indentured labor as Toni Morrison’s haunted masterpiece.”

That California is the source of so much contemporary literature, fiction, poetry and nonfiction—“more Californians have won Pulitzers in literature in the past decade than writers from any other region in America,” Freeman writes in the book’s introduction—made selections for California Rewritten difficult, he said. But two parameters made it a little easier. He wanted the authors to be alive, and he wanted to cover the gamut of California, not just LA and San Francisco. And themes arose, which seemed to naturally create sections.

So the book is divided into 12 sections, beginning with “Early Myths.” The first essay delves into Deborah A. Miranda’s Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir.

Myths, Landscapes, Sounds, Ruptures

The essay on Bad Indians begins with Freeman’s own memories of being taught about the California missions as a school kid. “It is astounding how long this destructive and delusional fantasy of benign coexistence sold by ‘the mission project’ has remained a core part of the California curriculum,” Freeman writes, despite the reality being genocide of the state’s indigenous peoples.

Miranda’s book, which includes poems, narratives, oral histories, field notes, “pseudo phrenological data” and other forms, is “a dazzling array of storytelling modes,” he writes. It delivers “vivid portraits of people,” her own people, the Ohlone—Costaloan Esselen.

Freeman quotes Miranda: “Maybe, like a basket that has huge holes where pieces were ripped out and is crumbling to dust and can’t be reclaimed, my tribe must reinvent itself—rather than try and copy what isn’t there in the first place.”

In section seven, “How We Sound,” one of the selections is Jaime Cortez’s Gordo. The short story collection is set in a farmworkers’ camp in Watsonville, and is based on Cortez’s own childhood. “To read this book is to feel part of a neighborhood, a place, one Cortez invites you into and allows you to watch as it asserts its boundaries through the eyes of a young, probably queer, slightly husky kid named Gordo. … That the sweat and labor of working happens off-screen, so to speak, speaks volumes.”

From Gordo, quoted by Freeman: “Primi loved a party. He splurged and rented maroon Bostonian lace-up shoes and a matching tuxedo with ruffles that made him look like a downwardly mobile rain forest rooster puffing up his plumes for one last mating dance.”

In the section “The State of Poetry,” Freeman includes musings on Lawrence Ferlinghetti and other poets. “On Gary Snyder” illuminates the poet’s very long life and literary odyssey, his “sensitivity to geography and our connection to land,” his many decades of studying Zen.

In section twelve, “Ruptures,” the reader finds Hua Hsu’s Stay True. “It begins,” Freeman writes, “as so many California stories do, in the car.” The book is about Hsu’s real relationship with his best friend, Ken, who is murdered. There are many references to books and songs of the times. “The songs, through their repetition, take on the power of a soundscape,” Freeman writes. “Of all these, the Beach Boys’ ‘God Only Knows,’ is the most lasting, with its repeated phrase, ‘God only knows what I’d be without you.’”

The Book as a Map

Freeman is aware that California Rewritten isn’t the kind of book most people will sit down and read cover-to-cover. It requires time to think about each book discussed, time to absorb what each one is saying about California, its myths, its deceptions, its beauty, its constant reinvention.

“The book is like a map,” said Freeman. “There’s no right way to read it.” But it wasn’t written for academics, he emphasized, but for “delight and engagement.” California has always been a place where “oddballs are welcome,” he said, “and I hope readers [find the book] as openhearted as California at its best. I’m just trying to help that along…it’s part of a conversation that began with a conversation.”

John Freeman speaks with Karen Tei Yamashita at 7pm on Oct. 16 at Bookshop Santa Cruz, 1520 Pacific Ave, Santa Cruz. bookshopsantacruz.com