Many people assume habitats are measured in extremes.

“Either untouched wildland or a parking lot,” frames Alex Hubner, horticulturist and Garden Steward at the UC Santa Cruz Arboretum & Botanic Garden.

In fact, as he and his wife, new Associate Director Lucy Ferneyhough, illuminate for me, habitats such as pollinator gardens are a confluence of nuanced factors.

“People’s perceptions of a perfect garden looks like something you’d see on the East Coast,” Hubner says. “Lush and green and full of giant flowers all summer long. The fact is, if you want that out here, you’re gonna have to use a lot of water, and you’re not going to be able to use native plants.”

Hubner and Ferneyhough are integral members and fervent proselytizers of the Arboretum’s Native Plant Program.

“Plant an array of different native species,” Ferneyhough says, “and you will see so many different types of bees and pollinators you haven’t seen before, or only out hiking. If you create the habitat, the animals will come.”

Ferneyhough and Hubner were both recruited to the Arboretum by Program Director Brett Hall, who has tended it since 1975. The two describe him fondly as a mentor giving youth lost in existential crisis purpose by spreading the gospel of gardening, a leader making new leaders.

Under his stewardship, the Arboretum team has collected seeds for more than 200 different rare plant species never before put into a “seed bank”—a library of flora built to sustain habitat destruction or climate change.

Hall got Ferneyhough into the California Naturalist Program, hosted by the Arboretum each year. A ten-week public course offered for optional college credit, participants meet on Thursday evenings, with weekend field trips. Wife and husband cannot sing its praises enough.

“You get this super holistic understanding of the landscape we live in that a lot of people rarely interact with,” she says. “People are so alienated from their own habitat in which all of our communities are situated.”

People are also alienated from each other, which the program also addresses, Hubner says.

“There’s an ecosystem of people doing this kind of work. You meet them and realize there’s something in common: appreciation for the sense of place.”

This place we call home has some parallels. Southwestern Australia, the city of Perth in particular. The Cape of South Africa. Parts of South America, especially Chile. But mostly, Santa Cruz resembles the Mediterranean.

“The climate regime where you’ve got these long, dry summers, and the wet winter,” Ferneyhough says.

The problem they’ve identified for home gardeners is misinterpreting dormancy as death, or that they did something wrong. If anything, the more wrong move is overdoing it—overclearing, overtidying, overwatering. Fastidiousness can be useful indoors, but outdoors, you can be disturbing the fauna just as they’re getting settled.

One mnemonic device to help you, as rhythmic as this couple finishing each other’s sentences: leave the leaves.

“Don’t remove the dead stems from this year’s grasses or wildflowers,” he begins, “until the rainy season comes—”

“—And you’re starting to see new growth again…” she continues.

“…Because bees will use the hollow dead stem to go down there and build nests for their young or hide from predators,” he finishes.

Even actual, unequivocal death can be a boon.

“A tree that dies in your yard,” she says, “you can cut to just chest-high so it’s no longer unsafe to have, then you can drill 3/8 inch holes on the north side that create a place for solitary bees to nest.”

Revamping a dead standing tree known as a “snag” qualifies it to be called a much cuter term.

“A bee hotel,” he says.

Raking leaves may feel righteous, an outdoor chore akin to washing dishes, but beware.

“Butterflies and moths often lay their eggs at the base of trees,” she says. “Then those larvae climb up into their host plant.”

Heat waves are increasing in frequency and intensity, but Ferneyhough cautions against endangering a plant while trying to “save” it.

“You’re going to want to make sure your plant is well-hydrated before the heat wave starts so that it isn’t sitting around in wet soil as the temperatures are going up. A lot of [native] plants are sensitive to fungal infection because they’re not adapted to a wet summer.”

No snazzy anti-invasive species marketing campaign exists, no warning labels informing customers the plant they’re about to purchase has the half-life of a plastic bag. But Santa Cruzans did get the memo about thirsty non-native green grass, as American as baseball diamonds, largely abandoning it as the drought made upkeep unrealistic and rationing by our water districts became punitive.

What’s a better choice?

“Buckwheat is beautiful, and bulletproof,” says Hubner. “And they bloom late, late summer into fall. You get that pollinator interest throughout the dry season.”

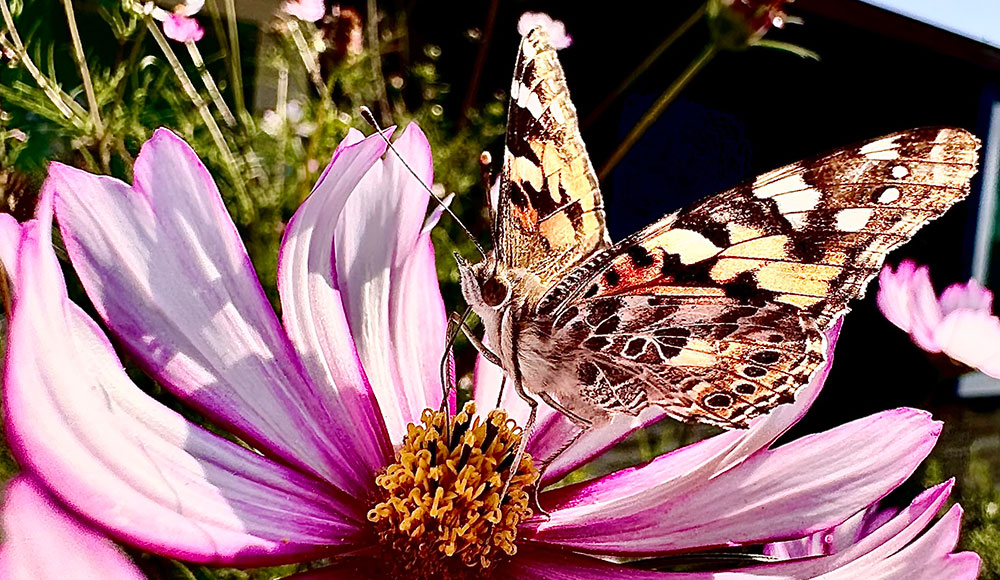

Nothing illustrates the interdependent evolution of flora and fauna like being a pollinator gardener. Plant long tube flowers and watch hummingbirds kamikaze for real estate rights. Plant short tube flowers and watch bees zip in and out. Pick the California native sticky monkeyflower and observe how it grows little landing pads for them. Behold nature’s immaculate design, devolving our attempts to assert our design over it.

“We’re at this peak human impact period,” Ferneyhough says. “Populations that are naturally small or are truncated by human pressures, whether it be development, or agriculture, or our spread of invasive species, could be completely extirpated or go extinct as a result of a single [catastrophic] event.”

In response, “Home gardens are providing linkages between fragmentation of the natural landscape. So much of the country, the state, our town is urbanized, and if you can create spaces for animals to be, you can reduce the impact.”

Pollinator garden starters, both native and exotics, are available for purchase at Norrie’s Gift & Garden Shop at the UC Santa Cruz Arboretum & Botanic Garden, including a local buckwheat. Visit them at 104 Arboretum Rd, off Empire Grade, or call 831-502-2999 to see what is in season.

Cultivating Pollinators

The following are tips excerpted from handouts provided by the UCSC Arboretum. Find more information on calscape.org, a website from the California Native Plant Society that allows gardeners to search by location for native plants suited to their local environment.

- For best success, plant in fall to take advantage of cool winter temperatures and rainfall. For new plants, water deeply 1-2 times per month during cool periods in the summer so they’re ready for any heatwave before it happens.

- Vary flower types: Hummingbirds favor tubular flowers, especially red. Bees gravitate toward blue, purple, orange and yellow short-tubed flowers, and daisy-like flowers. Butterflies are drawn to fragrant flowers with bright colors and a large landing pad. Moths seek out white flowers with a nectar spur, blooming at night.

- Prioritize native plants. Consider exotic species as an extra nectar source, but natives will support the insects that allow bird populations to reproduce themselves. Include larval host plants.

- Mix native species that flower at different times. Early flowering plants: Ceanothus species, Arctostaphylos species, Ribes (flowering currant) and clovers. Mid-season bloomers: Roses, mints, poppies, sages, lupines, Clarkia, Phacelia. Late flowering: California aster (Symphiotrichum chilense), seaside daisy (Erigeron glaucus), gumplant (Grindelia spp.), goldenrod (Solidago sp.)

- Willows and oaks host the largest number of butterfly larvae, so include these tree species if you have the space. Don’t spray your oak if it gets tent caterpillars.

- For monarch butterflies, plant nectar plants if you are within a mile of an overwintering site rather than milkweed (Xerces Society has an interactive map at westernmonarchcount.org). Plant milkweed further inland

For additional resources, visit homegrownnationalpark.org.

NEXT IN HOME AND GARDEN 2025—

Yoweeee. Great information and gorgeous photographs. Thanks to all!

Fantastic – thanks for this informative & helpful info!