Don Letts first came into my consciousness at the old Santa Cruz High School swimming pool. It was the late 1980s, and I was there working as a lifeguard, proceeding over a Saturday lap swim session. Also on duty that day was my friend Ben. We were both huge music fans who listened to a lot of albums that came from the UK—and thus were considered exotic and “alternative.”

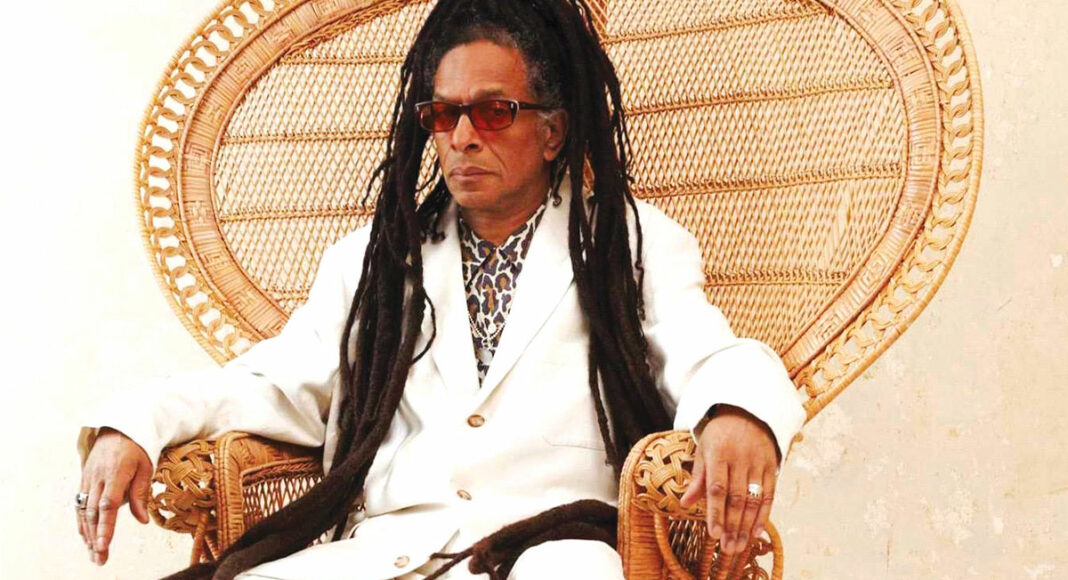

Ben had just been to the Catalyst to see this really cool band from London called Big Audio Dynamite (BAD). Fronted by Mick Jones, formerly of the Clash, BAD also featured a very attractive vocalist/samplist with dreadlocks down to his knees by the name of Don Letts. Letts looked cool and seemed like the ultimate punk-rock role model. Ben had somehow snuck by security at the gig and said hello to Letts in the parking lot of the venue after the show. I was awed by both his chutzpah and his close brush with someone who I saw as the human embodiment of awesomeness, while being completely jealous at the same time that it was not me who had not had a conversation with the rock god.

As I got older and information from across the pond became easier to get, I became even more of a fan of Letts. Not only was he an amazing documentarian for the Clash—one of my all-time favorite bands—he was an incredible filmmaker. From The Punk Rock Movie, his first venture in 1978 (shot on Super 8), which organically captured the emerging punk scene of the time, to his incredible BBC Four documentary The Story of the Skinhead, everything he touched just had an authenticity and ability to tell layer upon layer of a story that stayed with me weeks after I watched it. Even the music videos he made, ranging from PiL’s “Public Image” to Ratt’s classic “Round and Round” were able to convey a mood, a narrative, a message in the short four-minute format of an album single. Letts also seemed to have this strange, almost Forrest Gump-esque ability to be at the right place at the right time with the right people. How could one person be so hip?

However, once you meet Letts, it makes complete sense that he would know every cultural mover and shaker from the last 50 years, ranging from Bob Marley to John Lydon to Andy Warhol. The man emanates positivity and an almost manic vivacity that is impossible to not get drawn into. When I was asked to interview him for the launch of his new Omnibus book There and Black Again at the London branch of Rough Trade, I was beyond thrilled and honored. I wasn’t at Santa Cruz High lifeguarding this time, but I was going to have the opportunity to talk at length to someone who I had idolized my entire life.

I start off by telling Letts about a conversation I had with my aunt and uncle in which I tried to explain Letts by using an American equivalent, but failed miserably. Why were there not more people like him out there?

“Oh, man, you’ve stumped me already,” Letts says with a laugh. “Why are there not more Don Letts? The world couldn’t handle any more. Society made me this way. I was first-generation British-born Black, which kind of rolls off the tongue now. But it was a confusing concept back in the day. I was always made to feel like the poor relation—maybe that’s got something to do with it, not to mention getting stick for being Black. I was always having to stand up for myself.”

From the very first pages of There and Black Again, Letts confronts his own confusion with identity. As a child, Letts admits to almost being outside of himself, watching how other people’s ideas of who and what he should be played out, while the “real” him hovered like a spectre, trying to figure out where he fit in. I ask Letts if this made him feel isolated.

“When you’re young, you don’t really think about these things,” he tells me. “Suddenly, with hindsight, I realized I was suppressing my character to an extent. Women have a similar thing, in that if you have an opinion, you’re awkward, or you’re arrogant, or hard to work with. I didn’t realize that I was actually suppressing myself. But like a guy would ask me a question. I’d be like, ‘Yes, sir. No, sir. Three bags full, sir,’ speaking to him like that. But in my mind, I’m saying, ‘I want to talk.’ So it’s just been this weird duality of my existence to have to suppress myself and not make people realize I know a lot more about them than they know about themselves. When I went to school, I listened to what they taught me. Invariably, I know a lot more about white culture than white people do. They know diddly squat about me. It’s a deadly combination.”

It was this ability to listen and take in the world around him that allowed Letts to excel. As a teen, the emerging spirit of punk provided Letts with a credo that has stayed with him.

“The things I learned back then still serve me on a day-to-day basis,” he says. “I’m not talking about mohawks and safety pins. I’m talking about an attitude and spirit that I like to think has informed everything I’ve done. By meeting with these crazy white kids back in the day, it made me understand the punk in my own culture. For instance, the creation of reggae was a kind of punk rock. The guys couldn’t do the fancy Eric Clapton stuff; but they turned skanking into an art form. Brothers couldn’t sing, they start chatting on the mic. All of a sudden that becomes rap, and that took. So there was always a punk spirit that I just never recognized until I started hanging with those guys in the late ’70s.”

Letts does not shy away in Black Again from talking about his own confrontations with ideas of race, culture and belonging. In several parts of the book, he comes up against normative racism of various kinds, whether that be while talking to an executive at MTV or on travels with his family. I asked Letts about these trips, and how they changed his perspectives on himself and the world around him.

“I first went to Africa in 1991, for the independence of Namibia,” he says. “I found myself in a land where everybody was Black. It was mind-blowing. Not only that, but the most shocking thing was also that it wasn’t like they were like, ‘Hi, Don, my brother.’ I was dealing with a white film crew and they couldn’t quite make me out. It was an anomaly. I was the boss of these white guys. I had dreadlocks and I could speak like the white guys. I had to earn their trust. During that trip, I actually got lost in the Namibian desert. I almost fucking died. It was there that I realized that I was like the lost tribe: so civilized, I couldn’t deal with the roots of my own culture. It was a life-changing moment—although two weeks back home, I forgot about it.”

Does he think things have changed in the last 30 years in regards to racism? “The way the world is, I’m in my creative bubble, doing my shit,” he tells me. “Outside of London and Bristol and a few other hip cities, the rest of the UK is like the goddamn 1950s. Why do you think Brexit happened? That George Floyd thing was a major wake-up call. There isn’t the progress that we think we’ve made. That was a drag. While Covid was going on, you had the whole BLM thing happening. I’ve been at this game for a long time. I’m 65 years old; I’m as old as rock and roll. But [race] is still the most contentious argument on the planet, because we can’t get past that. We’re gonna get past anything else. Because you know what, we ain’t going nowhere. People love Black culture, but they do not love Black people.”

I start quizzing Letts on all of the music videos he had made, as some of them—like Elvis Costello’s “Every Day I Write The Book,” with its Princess Di and Prince Charles story line—are among my personal all-time favorites. I’m astounded when Letts tells me he has made upwards of 400 videos. However, the medium is not one that he plans to return to.

“I don’t do them anymore, because they don’t want people like me. Back in my day, as a filmmaker, you’re always trying to put a little bit of contention or trying to get something across. After a while, record companies didn’t want me doing that anymore. Classic example would have been that whole shenanigans with Musical Youth. I did a couple of videos for them; they made number one in 20 countries around the world. Then the record company said I was making them look too naughty—which was actually their attraction—and they threw me off the project. We didn’t hear about them anymore. I am not saying that it is down to me. But videos are not for me anymore. Recently, the landscape has changed because there’s brilliant things happening within that world, because they’re not just adverts for records anymore. They become artistic expressions.”

Letts did dust off his video skills for the 2020 Sinead O’Connor cover of Mahalia Jackson’s “Trouble of the World,” in aid of Black Lives Matter.

Dancing and going to gigs also plays a huge role in Black Again. In a moment when there has been over a year without any of these sort of spaces for teens to go, I ask Letts how important such places were for him in finding his love for music.

“They were absolutely crucial,” he says. “Not just for me; I think they are crucial for most young, teenage adolescents. They are where you find your identity, you express your sexuality. The whole tribalism thing comes into it. But I guess the Black thing comes into it, because we weren’t allowed into a lot of clubs back in the day. We had to find our own spaces to entertain ourselves, through no fault of our own. It was ghettoized, because society forced you into these situations where you’re in a soul club with all your Black mates. But then here is what’s interesting: The white kids were creeping in because they were drawn in by the style and the music and the culture. At a grassroots level, it was music that was uniting the people of this country. It was happening on the dance floors of soul clubs and reggae clubs.”

As a native Santa Cruzan, I tell Letts stories of going “over the hill” as a kid to the dance mecca that was One Step Beyond, seeing a pre-“Baby Got Back” Sir Mix-a-Lot and attending a goth night where I swirled around to tracks by the Cure and Sisters of Mercy. Does he remember the first club he ever went to?

“It was called the Lansdowne Youth Club. I was 14,15 and that’s when the skinheads were happening. Skinheads back then weren’t the racist motherfuckers they are now. They were sort of amalgamation of white working class kids with Jamaican rude boy style; it was a beautiful thing for a while,” he says. “Club culture in the UK has played a tremendously important part in uniting the people. I mean, much more so than bloody church, state and school, you know?”

His book reveals that the dance craze caused by the 1974 song “Kung Fu Fighting” by Carl Douglas played a big part in building up a young Letts’ confidence on the dance floor. When asked about this revelatory scene, he laughs.

“You might have blown that out of proportion,” he says with a grin. “It just got us doing a really stupid dance. In my youth, I was fat, four-eyed and Black. I really didn’t have a lot going for me. So when I lost the weight and learned a few moves, I went for it because it was the only way I could express myself. I was never a macho kid. Never did the football thing. I was never physical.”

Strong women play a role throughout Letts’ life, a fact that he does not shy away from in the pages of Black Again. From vivid descriptions of his mother to the different romantic relationships he has throughout his life to his film Dancehall Queen, Letts seems to surround himself with indomitable ladies. I ask him how important strong women have been in his own evolution.

“Women have always fucking ruled the world, so why wouldn’t I spend my time in the company of the people that really run things and keep shit together?” he says.

Towards the end of the book, Letts recalls time spent with a budding artist named Jean-Michel Basquiat. “I knew the brother briefly while I was in New York in ’80-’81, and when he came into the UK. He wasn’t a massive thing that he is now, but he stood out a mile from all the other stuff that was going on. There’s no two ways about it,” Letts recounts.

I ask about a discovery Letts later made of his name scrawled in one of Basquiat’s pieces. Where can I see this merger of two of my favourite contemporary creatives? Letts confides that it’s not “a proper painting,” it’s just one of Basquiat’s “doodles” (note: I would personally be pretty pleased with that). Basquiat had offered to sell Letts a painting.

“I wanted to have a piece of his work,” Letts recalls. “I remember negotiating with him in my front room and the best price he could do was like 5000 pounds, which I couldn’t stretch to at that time. I’m just glad to have been in the brother’s presence.”

Another Forrest Gump moment is Letts’ run-in with pop guru himself, Andy Warhol.

“It was backstage at Shea Stadium. I did a video for the Clash’s ‘Should I Stay or Should I Go?’ He [Warhol] comes backstage because they were kings of New York for that period of time. To be honest with you, I was a dick. I told Andy that there was acid in the pineapple upside-down cake that someone had given him. It totally freaked him out. On reflection, what an asshole I was. He was totally freaking out and he left. I’m not always cool.”

I tell Letts he was cool to my friend Ben back in 1987 when the two met in the Catalyst parking lot. “That sounds very dubious. OK,” Letts replies.

Don Letts’ memoir ‘There and Black Again’ will be released May 20 on Omnibus. Dr. Jennifer Otter Bickerdike is a Santa Cruz native living and writing in London. Her new book, ‘You are Beautiful and You are Alone: The Biography of Nico,’ will be published on August 20 by Hachette Books.