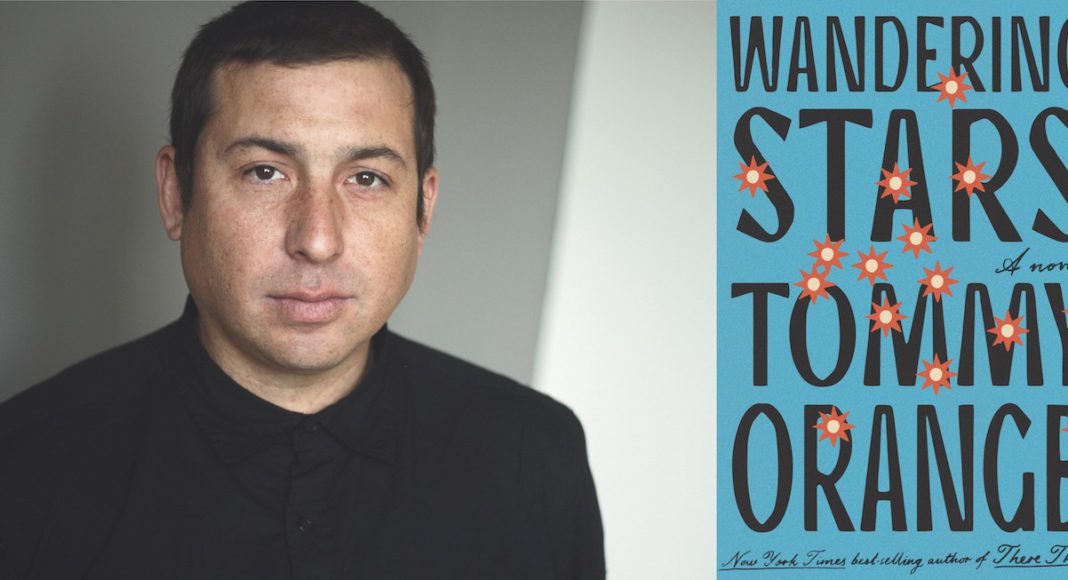

It’s a Monday morning in early February and Tommy Orange is feeling nervous. He’s about to embark on a months-long, cross-country publicity tour for his upcoming sophomore book, “Wandering Stars,” which hits stores on Feb. 27.

It’s been six years since his hugely successful debut novel, the 2019 American Book Award winner “There, There,” lit up the literary world and gave voice to a wide spectrum of Native American experiences. Now, the Oakland author has become one of the most widely-acclaimed writers of his generation, and is booking large event halls throughout the 17-date spring tour.

“I’ve done a lot of public speaking since the first tour. And so, that’s not the part that makes me anxious,” Orange, 42, says in a phone interview. “It’s just the attention that can be a lot, and I think writers are pretty private people.”

“Wandering Stars” is sure to elevate Orange’s profile. The ambitious sequel to “There, There” takes on the painful history of Native American boarding schools in the U.S., which served as brutal reeducation sites for Native children for the better part of a century. Orange immerses himself in a work that is both haunting historical fiction and contemporary literary prowess.

In the novel, the family lineage of Orvil Red Feather—a central character in “There, There”— collides and entwines with the shameful legacy of the Carlisle Indian School. 160 years of history are told through the lives of Red Feather’s ancestors, from the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864 to present-day Oakland.

GT spoke with Orange about his upcoming book, the effects of writing during the pandemic and his efforts to bring Native Americans beyond historical relegation in the American popular imagination.

Good Times: In a 2018 interview, you said that you wrote “There, There” out of a place of loneliness, out of a lack of representation for the range of Native voices. What place were you in when you began work on Wandering Stars?

Tommy Orange: I actually started in March of 2018. I just got excited about just doing a sequel and kind of staying in the world of “There,There.” The metaphor of the aftermath of the shooting seemed like a really layered and textured, deep metaphor for the way history plays on the present. And so, Orvil kind of, like, recovering from a shooting at a powwow, it just felt like there were a lot of layers to it. So I got excited about starting to write into that and was also very wary of doing a sequel because you’re almost dooming yourself to writing a less-good book. And for your sophomore effort, that’s the thing you really don’t want to do.

So, it was kind of a weird decision on my part, but I still was in a similar place when I started writing. And then after two years of writing it, the pandemic happened. I’ve been in a lot of different head spaces during the writing of “Wandering Stars.” And part of that was not being lonely. [Now] we’ve got two TV shows put out representation-wise, and a lot of Native books have been published since then. And I probably feel a lot less lonely representation-wise and got to see a lot of Native people react, including a ton of non-Native people. But a lot of Native people across the country reacted to the book in really positive ways. So that was good.

GT: Did the pandemic’s isolation help you in your process?

TO: No. It was a very distracting time. I sort of lost a lot of structure and routine, which I like to have. You know, not being sure how long this thing’s gonna last. If this was the beginning of some kind of end of the world. That was not conducive for me being in a good writing space. I think a lot of people put out really big books right after that time period. So, some people were really able to take advantage of it.

GT: You’ve said before that contemporary depictions of Native Americans relegate them to the historical. How does “Wandering Stars” explore the generational trauma of Native American boarding schools to inform the book’s characters in the present?

TO: Yeah, so I think a lot of the time, we have only been depicted historically and a lot of times it’s a 400-year-old history, it’s like related to the pilgrims or it’s “Cowboys and Indians.” I think a lot of times we get authenticated from the outside and people kind of look at us as not being Native enough, or not the Native that they had in mind. And it [brings out] a lot of the burden of [questions like] ‘Where’s our language?’ and ‘Where’s our connection to culture?’ especially for urban folks who have a complicated history.

The burden kind of gets put on us like there’s some kind of weakness. And a lot of people don’t know that in these boarding schools we were being punished for practicing our lifeways and our languages. And these boarding schools went on for decades, probably 100 years with the same mentality of ‘Kill the Indian, save the man,’ and so a lot of people’s connection to their culture, their tribal ways, was cut off intentionally.

And so, portraying the historical piece and then having the contemporary characters kind of struggling with ‘What does it mean to be native?’ it just kind of shows that the fact that we still are connected at all is a lot. It’s trying to show our strength rather than something that we lack.

GT: Part of this book takes place in Oklahoma, a place you have a personal connection with. What was the significance of that while writing this book?

TO: I grew up going back to Oklahoma, that’s where my tribe is and my family that lived there, but it was more the historical piece because that’s where people went after Fort Marion and that’s where my tribe was. That’s where our reservation, our tribal jurisdiction land is. It had more to do with this historical piece. And I did a lot of research.

It’s a complicated thing. Some people have tribal homelands… they’ve been on a piece of land for hundreds—some maybe even longer than that—years, being relegated to this piece of land by the government, and not really being allowed off of it for a while.

It’s not the same feeling, like, ‘that is home.’ We were in different parts of the country before that, getting moved around and the Sand Creek Massacre and all that stuff. So I have mixed feelings about the place.

GT: For this upcoming event you will be in conversation with acclaimed author and Oakland native Leila Mottley. Are you a fan of hers, and how does it feel to be a part of a contemporary Oakland literary community?

TO: I love her book and she’s got a book of poetry coming out this year, I think. We’ve just been in contact through email, so I haven’t even met her in person, but I love her work. I wish there were more prominent Oakland authors and I hope that there will be more in the future, but it’s great to have somebody’s book from Oakland get the kind of attention that she got. So I was really happy to see that.

I don’t see any evidence of [a literary movement]. Even Leila’s book came out a little while ago and we haven’t seen [more literature]. For the amount of books that come out of New York, it’s really nothing, a drop in the bucket. So, I think the West Coast gets a lot less love in general. So I don’t see it, but I hope to for sure.

GT: Your work gives life to an array of Native experiences and you have garnered wide acclaim for the depth of your depictions. On the flipside, do you ever feel tokenized in an industry that tends to fetishize “other” narratives?

TO: Yeah, and I think sometimes people… I’m like, the only Native author that they know and I’ll get questions that I’m supposed to be able to answer for the entire community and it’s really not something that I can do. We’re almost 574 federally recognized tribes, and there’s like 400 not federally recognized tribes, and everyone has their own worldview and histories and so there’s a lot of diversity that makes it impossible for me to speak for. But, I do feel put on the spot sometimes to answer from that point of view, but I don’t know that I necessarily feel tokenized.

Tommy Orange will be in conversation with fellow Oakland author Leila Mottley Thursday, Feb. 29 at 7 p.m. at the Veterans Memorial Building in Santa Cruz. The event is sponsored by the UC Santa Cruz Humanities Institute and Bookshop Santa Cruz. Visit bookshopsantacruz.com to get tickets.