For five decades, the National Women’s Hall of Fame has honored the achievements of American women, starting in 1973 with a group of 20 inductees that included such familiar names as Harriet Tubman, Susan B. Anthony and Amelia Earhart.

This year the Hall of Fame—the nation’s oldest nonprofit organization dedicated to honoring women—made history itself by honoring a trans woman with an award.

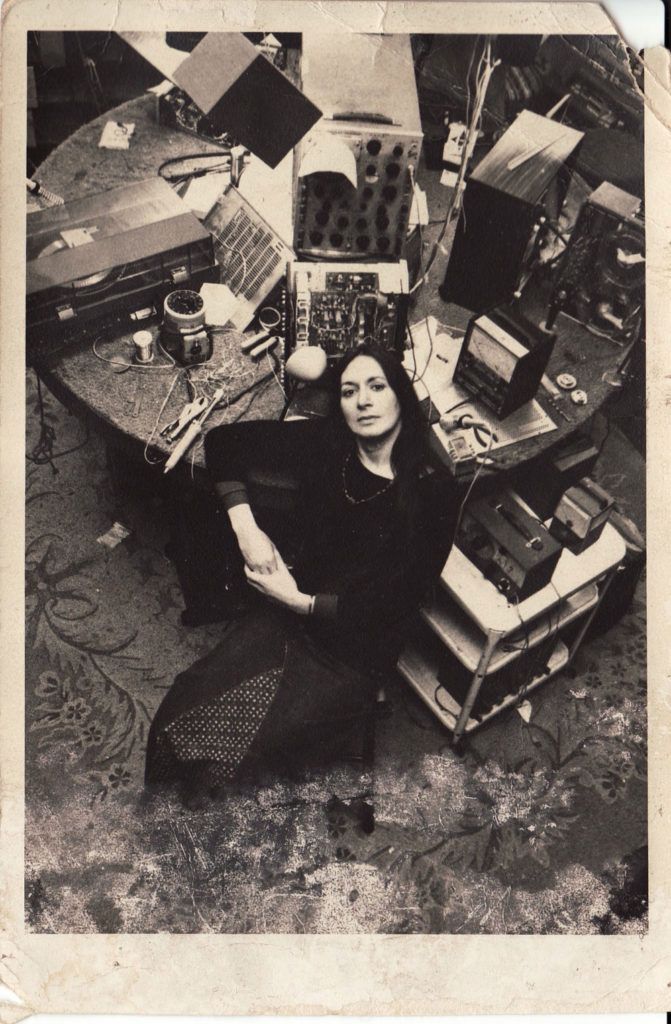

That woman, Allucquére Rosanne “Sandy” Stone, was recognized for a lifetime of work that has spanned multiple fields: audio engineering, radio, performance art, academia and more.

A prominent figure in her various fields for more than 50 years, Sandy Stone is an integral part of the Santa Cruz community, from her years as an entrepreneur, an academic at UC Santa Cruz, and an engineer at community radio station KSQD. Next year her story will reach an even wider public with the release of a new documentary, Girl Island.

Sound and Vision

Born a Jewish boy, Sandy Stone was fascinated by the whole concept of recording sound. “There was something magic about the idea that you could transform one medium into another,” she says. “You could get the sound of someone singing and then make it into a physical object that you could hold in your hand.”

She emphasizes that on its own, said handheld object—a vinyl record or a reel of tape—didn’t make any sound. “But you could put it into a machine out of which noise came. I thought, ‘This is amazing,’ and I wanted to do more.”

So she did, beginning to work as a recording engineer in the 1950s, when she was still a high school student in New Jersey. But Sandy would have to be self-taught. “There wasn’t anybody else I knew that was doing it,” she says, describing herself as a geek, one who found it challenging to communicate her thoughts and feelings to others. “I was interested in how geeks—who are normally very retiring—communicated with the world.”

Sandy decided that sound and light could be her media, tools with which to communicate those feelings. As far back as the 1950s she put on performances of what are now known as light shows. She also programmed scores to accompany silent films. Her criteria for selecting the music was straightforward enough: “This is moving,” she would think to herself. “Will it move other people?” The term multimedia wasn’t yet in wide use, but Stone was already pioneering in the field.

Basement Tapes

Her recording endeavors continued apace as well. “My first recording studio was in the basement of my parents’ home,” she recalls.

Through a series of connections, she found herself documenting the work of a legendary musical figure.

“A person named Dick Spottswood had just done this somewhat jaw-dropping thing of finding Mississippi John Hurt,” Stone recalls. The country blues singer and guitarist had begun his musical career in the late 1920s, but when a series of 78 RPM record releases failed to jump-start his career, he returned to a life of farming. More than three decades later, musicologist Spottswood tracked him down in Avalon, Mississippi.

In 1963 Spottswood convinced the musician to come with him to Washington, D.C., and make new recordings.

“But Dick didn’t want to take John to a regular recording studio,” Stone says. “He wanted something that would be a little less intimidating.” As it happened, Stone had built a studio in her log cabin home near Annapolis, Maryland. Through intermediaries, Spottswood reached out to this recording engineer whom he did not know. “Next thing I knew,” Stone recalls, “I was shaking hands with Mississippi John Hurt.”

Hurt and Spottswood moved into Stone’s studio, remaining for a week. “I had the recording equipment set up 24 hours a day,” Stone explains. “When they felt like recording, I would turn it on.”

As a result of the informal setting, there’s a spontaneous, audio verité quality to the recordings. The cuckoo clock in Stone’s kitchen even makes itself known. “We just let the tape roll,” Stone says. From those monaural master tapes came 1963’s landmark Folk Songs and Blues, released mere days after Hurt’s performance at the Newport Folk Festival. The album and concert led to a revival of the bluesman’s career.

Working at the Plant

By the late 1960s, Stone would land a job at a new recording studio in Manhattan, the Record Plant. Launched by Gary Kellgren, the studio was an innovative enterprise, one of the first studios to make use of a 12-track recording console. Stone cold-called on the studio doorstep in hope of getting work. Yet while she was quite experienced as an engineer, none of her experience had been inside a major studio. “Somehow I got them to open the door for me,” she recalls. “I told them, ‘I’m the greatest recording engineer in the world!’” Kellgren was unimpressed, but Stone persisted, claiming that she could fix anything.

As luck would have it, at the moment the studio’s Scully 12-track console was broken. Kellgren asked Stone if she could fix it. “Oh, of course; I fix them all the time,” she lied. “But I don’t have the instruction manual with me today.” She asked to borrow it; Kellgren said yes. “And his fate was sealed,” Stone says with a mischievous chuckle. “I speed-read the manual!” She fixed the machine, and was hired on the spot as an engineer.

In short order, Stone found herself working in the studio with Jimi Hendrix. “He was a sweet, warm guy, and a perfectionist,” she says. Stone helped devise technological methods of realizing some of the bold concepts Hendrix had in his head. “Some of those ideas were kind of obscure and psychological,” she says, “and some of them didn’t exist at all.”

Stone recalls an amusing anecdote about Hendrix. “Jimi had a huge desire to put his hands on the [recording console],” she says, noting that musicians weren’t permitted to touch that equipment. “So Gary made Jimi a little box with knobs all over it, and a thick umbilical that came out and went into the console,” Stone explains. “It did nothing, but Jimi didn’t know that. He had a wonderful time with those knobs.” Even though she enjoys sharing that story, Stone makes it clear that she recognized Hendrix as a musical innovator. “We developed a deep friendship and appreciation of what each [other] was doing,” she says.

Stone was instrumental in outfitting a console for Record Plant’s Studio B in Manhattan. At a gala party to celebrate its opening, she found herself in conversation with many big names. “Drugs flowed with incredible freeness,” she admits. “At one point, I found myself sitting on the floor with my back to the wall, because I couldn’t stand up.” There she engaged in deep conversation with brothers Edgar and Johnny Winter. “But I can’t possibly remember what we talked about,” she laughs.

As a result of Stone’s critical role in studio setup, Kellgren wanted her to do that full time, traveling around the country opening up new Record Plant branches. But Stone wanted to record. Kellgren issued an ultimatum. “ I used the IBM Selectric typewriter at the front desk, and typed out a note,” Stone recalls. “’Dear Gary, I hereby resign. Signed, Sandy.’” She left her keys on the desk and never returned.

Stone soon relocated to the West Coast. Over the next few years, she would work closely with some of the biggest names in popular music. Her résumé includes sessions for Van Morrison, the Byrds, Crosby and Nash, Joni Mitchell and many others; some of the more off-the-wall and obscure artists included Lothar and the Hand People, a group that made use of the otherworldly theremin. “It was a grand and glorious time,” she says.

‘Nobody Had a Language for That’

All through those years, Stone had feelings that she didn’t fully understand. She says that the New York scene was populated by many gay and bisexual people. “They were hitting on me, and I had no idea why,” she says, “because I wasn’t yet facing what was going on with me.” Eventually she realized she was unknowingly giving off signals. “But nobody had a language for that,” she says, “so it was interpreted as gay.” It wasn’t until Stone relocated to San Francisco in the 1970s that she came to terms with her gender identity.

Stone recounts a recurring dream she had as a young boy. “I used to dream of this place that I called Girl Island,” she says. “There were a lot of other people with whom I was doing all sorts of strenuous, nature-type things: swimming swift rivers, building canoes, learning to climb trees, talking to animals.” In the dream Sandy was a girl, too. “We were all little girls,” she emphasizes, “but we were not doing anything that little girls at that time did.” She says that while the dream was persistent, those thoughts never entered her waking mind. But they remained a part of her subconscious.

Stone left the world of mainstream studio production and engineering in 1974. To make ends meet, she took a job at a stereo repair shop in Santa Cruz. She began identifying as a woman, but when she went public with her transition, Stone was immediately fired. “So I scuttled across the street like a little crab,” she recalls, “rented a storefront and opened my own stereo repair business!” Her business, The Wizard of Aud, thrived while her former employer’s shop went bankrupt.

Stone’s shop eventually attracted the attention of what she calls “the queer element in town.” Her storefront became a popular LGBT space. Soon, members of Olivia Records approached her with an offer to collaborate.

A lesbian separatist collective, Olivia Records was a label dedicated to women artists. “Oh, great!” Stone thought to herself. “Another adventure! When I got to the collective, I looked around and thought, ‘This is Girl Island!’ They were a bunch of strong women, working together on a high and common purpose, and it had nothing to do with being a stereotypical woman in society.”

Gender Revealed

Stone was living as a woman, but she hadn’t yet undergone any medical procedures to make that a full reality. “I had been approved by Stanford a long time previous, but I didn’t have the money for the surgery,” she explains. “So in the meantime, I was trying to live my life as best I could. I had all this talent, and here was a way that I could use it in a way that not only helped the collective, but that agreed with my politics at the time.”

But eventually, Stone realized that her then-current biological status put the collective at risk. After three years working with Olivia Records, Stone scheduled gender confirmation surgery at the Stanford Gender Dysphoria Program in Palo Alto. But she made that journey largely on her own. Lacking the funds for the operation, she revealed her status to the core collective. “They were angry and horrified,” she says today, “because I didn’t trust them to tell them originally.”

The collective offered to provide the gap funds needed, on one condition. “Do it in secret,” she was told. “Nobody knows: not your family, not your friends, not the rest of the collective. Nobody.” Surgery was scheduled for September 1977. “And the core collective worked out a way for me to disappear,” Stone says.

Because of some legal matters at the time, Stanford’s gender confirmation surgery program had been relocated to Chope Community Hospital (now San Mateo Medical Center). Stone says that the change of setting posed some challenges for the medical staff: “Where do we put a trans person?” The answer was the hospital’s prison ward. “So on top of everything else,” Stone says, “with no support network and all this weird, disaffirming stuff, I just went straight ahead and went through the whole thing.”

Lesbian feminist scholar Janice Raymond published her book The Transsexual Empire in 1979. Highly critical of trans persons, the book included a specific and scathing attack on Stone. While the collective initially defended her, in the face of a boycott against Olivia Records, Stone left the collective in 1979, returning to Santa Cruz.

Back to School

Stone recalls that she had “burned out” on education during her high school years. “I had avoided academia like the very plague; I didn’t want anything else to do with it,” she says, But by the early ’80s she had reconsidered. “Maybe I should give it a try again,” she thought. She met scholar Donna Haraway, a professor in UCSC’s History of Consciousness program. Stone applied for a spot in the teacher’s assistant program, and landed the job.

Stone discovered that she had to play the game to get along. “Faculty members began saying things like, ‘If you want to get into this program, we need to become less afraid of you. Go to parties. Hang out.’” So she did. “I learned to talk like an academic, and a year later, I got accepted into the program.”

One summer day in Santa Cruz, Stone passed by the popular Porter College squiggle sculpture affectionately known as the “flying IUD.” And at that moment, she had a vision. “I saw in front of me a circus train, and each car was painted to represent one of my careers,” she recalls. “At the back of the caboose, there was a clown with a red nose, and he was waving at me.” To Stone, the vision represented all of her previous careers going away. It was then that she realized that she was where she belonged. “I don’t think I’ve ever belonged before,” she says. “And that’s how I became an academic.”

While working on her doctorate, Stone authored a groundbreaking essay (and pointed response to Raymond) titled “The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttransexual Manifesto.” Stone’s time in academia had its ups and down: she would be called upon to provide a syllabus for a women’s studies program, only to find that her grant had been withdrawn. The turmoil took its toll. “I was so unhappy at that time that I found a way to cry that nobody would know about,” she says. She would cry her heart out while on a slow elevator on campus, and then steel herself before the doors opened.

Almost immediately after being fired from an academic position in San Diego, Stone was “headhunted” away to the University of Texas. She recalls marveling to herself, “You’re being offered a tenure-line job in a department that wants you to start a new line of study.” She took the job in Austin. In 1993 she launched a New Media program called ACTLab (Advanced Communication Technologies Laboratory). The program would become a leading light in the nexus of the arts and new media.

In 1995, Stone married author and researcher Jeffrey Prothero (Cynbe ru Taren). Years after gaining tenure, Stone retired from the position in 2010, continuing as professor emerita. Her spouse passed away from cancer in 2016.

Radio Days and Beyond

A love for community radio led her to KSQD. At loose ends and still grieving from the 2016 death of her husband, she agreed to get involved as the station’s chief engineer. “I physically built the station,” she says. According to a KSQD press release, Stone—who celebrated her 80th birthday several years ago—continues to provide technical and organizational expertise to the station.

Dr. Sandy Stone is pleased to have received the recent honor from the Women’s Hall of Fame. (The ceremony was telecast on Oprah Winfrey’s OWN Network). “It’s a great honor for me as a woman, as a person,” she says. “But it’s complicated.” She notes that her acceptance speech focused upon the ways in which the concerns of trans women and non-trans women coincide.

“We all agree on a number of very important things,” she emphasizes. “We’re together fighting hatred and bigotry and venality.” But she says that trans women bring an important perspective to those discussions. “As trans, we have a particular vision. We see beneath the smooth surface of the world to the way the guts are put together.” She believes that her perspective is about unscrewing that metaphorical lid, and putting the world back together in a more just fashion. The challenge, she says, “is to be able to implement that.”

Marjorie Vecchio, an artist, first-time filmmaker and Stone’s longtime friend, launched a Kickstarter campaign a few years ago. More than 400 backers pledged funds to help make her documentary a reality. Due in 2025, Girl Island: The Sandy Stone Story is, in Vecchio’s words, the tale of “America’s most modest rebel.”

Sandy Stone’s journey so far has been a remarkable one, as inspiring as it is instructional. She has lived through eras in which matters of gender identity weren’t discussed openly, yet she has triumphed in turn at each endeavor to which she has applied herself: engineer, author, academician.

“I have a nice plaque,” Stone says with a smile. “I am greatly honored by it. But that’s as far as it goes. It makes no change in the world other than what we bring to it. But I want that change, so I’m going to use it for whatever leverage I can.” ⬛

I look forward to seeing this doc, “Girl Island”, and appreciate the content of this article.

Sandy fixed a console for me back in 1979 or 1980 at her workshop. She charged me only $50, which was a deal considering how much restoration she did. It worked beautifully.

She referred to herself as a “trans-sister” which I thought was a clever twist on words.

What a GREAT story, Bill! Blown away!

What an honor it was to engage in conversation with Dr. Stone. She has some stories!

Fascinating story and beautifully written piece. Thank you!

What an amazing Trailblazer!

Thank you so much, Bill, for such a thoughtful and in-depth article about Sandy’s amazing history! Marji

I first met Sandy in the role of recording engineer back in the early 1970s. As a player, I rarely enjoyed the sound quality I was hearing on playback in studios. So, of course, my first session with Sandy changed everyting. Finally, the recordings not only sounded right — they were even clearer, larger, more impactful. Alchemy? Wizardry? WTF!! The studio is an instrument, and Sandy not only knows how to play it…she knows how to build it.

Lucky to have had Sandy as a dear friend and audio sage for over 50 (gulp) years.

I enjoyed an all-women Yosemite backpack trip in ‘79 and an ‘81 Alaskan kayak trip with Sandy Happy to be part of her Girl Island. Great story, congratulations.