“I consider myself responsible to the coming generations, which are left stranded in a blitzed world, unaware of the soul trembling in awe before the mystery of life.” — Oskar Kokoschka

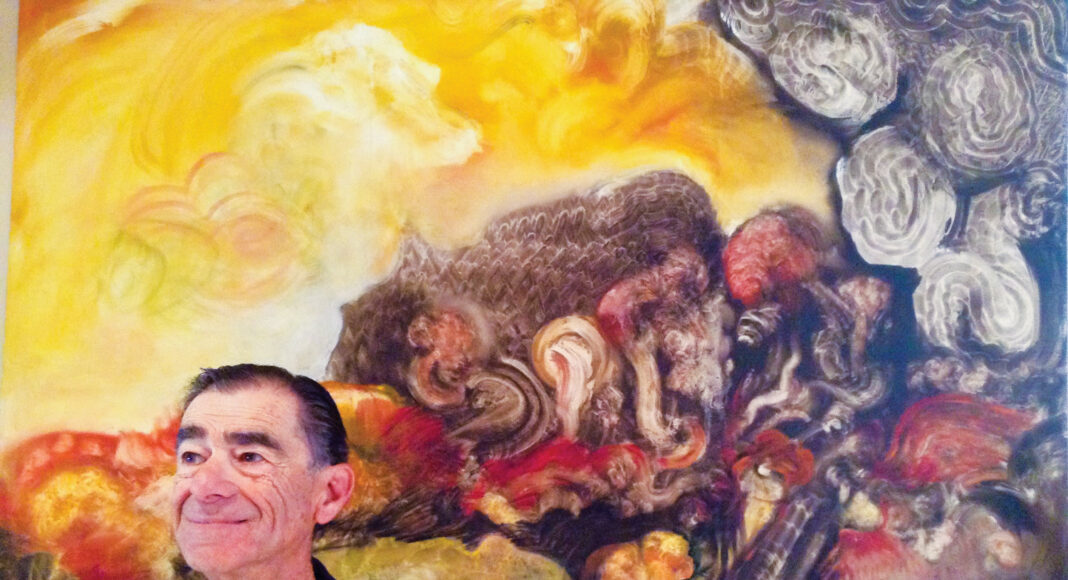

Casey Sonnabend’s name might sound familiar. You’ve seen his work. He might even be a genuinely important American artist. Yet, outside of certain lofty circles, he’s totally unknown. And that’s by design. Like a prankster bullfighter, the longtime Santa Cruz resident has dramatically sidestepped success for 65 years. And in a world where metrics are tied to everything, the 88-year-old still refuses to be counted or labeled.

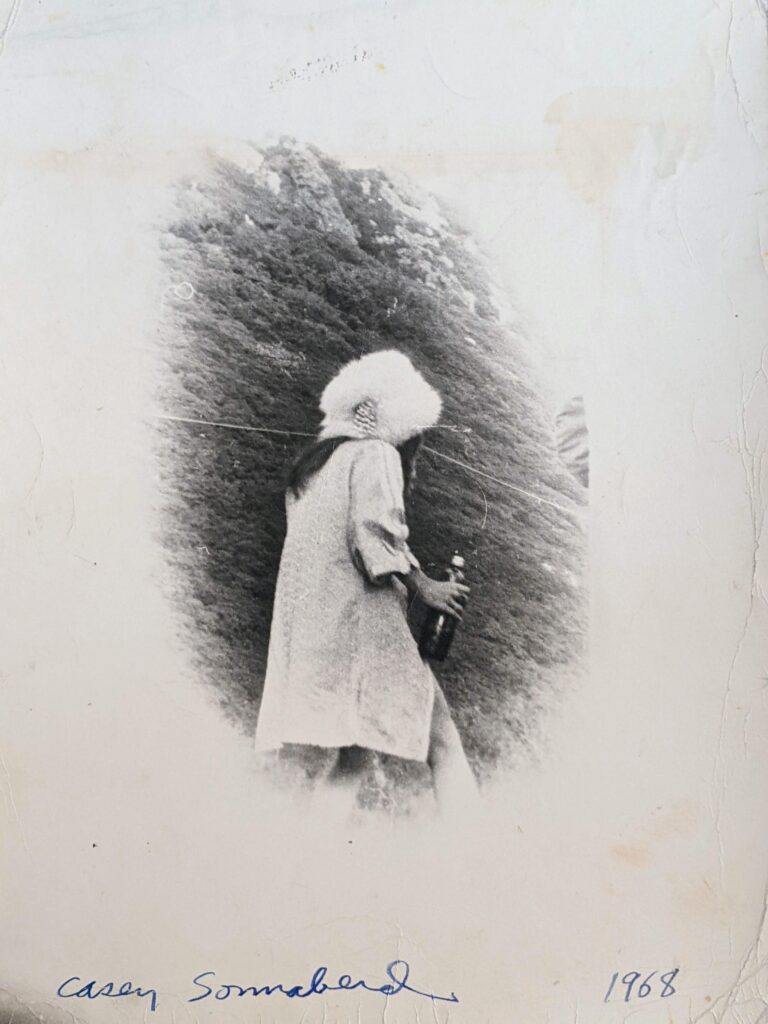

Sonnabend jammed with North Beach jazz bands in San Francisco, backed up the Kingston Trio and served as the Quicksilver Messenger Service’s first drummer—yet insists he’s neither beatnik nor folkie nor hippie. He studied under the legendary German Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka and has consistently painted for 65 years, yet refuses to show his work in public. His one-man photography show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art was critically acclaimed in 1963, but he fled to India before it ended, leery of the recognition—only to capture one of the most iconic, enduring images of the Summer of Love.

Sonnabend loathes name-dropping, yet his personal stories are rife with famous musicians, writers, artists and academics. He also despises money. Other than a stint in the U.S. Navy and a few years behind the counter of the Tides Book Store in Sausalito, Sonnabend has never “lifted a finger for a dime.” That’s not saying he hasn’t worked—65 years of paintings, photos, writings and mementos packed into 2,500 square feet of a Marin warehouse space say otherwise. This mammoth, untapped repository represents Sonnabend’s life’s work.

Sonnabend’s self-imposed path of “purity and obscurity” hasn’t been easy. He spent 25 years living in a van parked outside his ex-wife’s Westside Santa Cruz house. He had to watch another man raise his kids with the woman he never stopped loving. He swallowed his pride again and again, a thousand times over, yet stubbornly stuck to his guns, refusing to get a job or sell artwork or memorabilia from his trove in Marin.

Casey Sonnabend has suffered “great heartache and hunger” for his art, but he’s lucky to have friends who respect and love him for who he is and how he’s lived his life. Until her death on Dec. 11, 2021, for example, Sonnabend received regular payments from Interview with a Vampire author Anne Rice to keep him fed and in art supplies. Yes, Sonnabend says, he’s been very, very lucky.

Questionable Beginnings

Sonnabend was born in 1933 to Herman and Katherine Sonnabend. The two bohemians had recently moved back to Buffalo, New York from Paris, where they’d been living as artists with Herman’s brother Isaac. (Isaac, or Izzy, would invert and alter the spelling of his name to Casey before eventually changing it to Michael). Katherine was in a sexual relationship with both brothers, according to family lore, but Herman won her because he was willing to get a job.

“There’s always been some question who my father was,” says Sonnabend, pulling a boyish rubbery grin and knitting his dark eyebrows. “But they named me after my Uncle Casey.”

Sonnabend grew up immersed in art, literature and music. Uncle Casey would take his young nephew through the museums, providing a running monologue on art history while gesturing at small details on the canvas with a pinkie. “The first two paintings that killed me were ‘Hide-and-Seek’ by Pavel Tchelitchew and ‘The Sleeping Gypsy’ by Henri Rousseau,” he says. “Both of those were magic paintings. They just glowed.”

Sonnabend’s father worked as a style magazine editor, but aspired to fabric entrepreneur. Seeing opportunity on the West Coast, he moved the family from New York to Los Angeles in 1945. While Sonnabend worshipped Samuel Beckett and continued to haunt art museums as a teenager, music consumed him. He’d begun playing drums at the age of five, so by the time he was a student at Fairfax High School, he could read music and confidently play most styles. “I didn’t have jazz chops, but I could play just about anything else. I wanted to have fun with music,” he says. “My dream was to play in Spike Jones’ band.”

Missing the Beats

After graduating from high school in 1951, Sonnabend went to L.A. City College for a time. “I hated it. There was nothing there for me,” he says. So, he joined the U.S. Navy in 1953. “I volunteered so I’d get assigned to the band,” he says. “I was going to get drafted anyway, and guys I knew were shooting off their toes to avoid Korea.”

From 1953 to 1957, Sonnabend played drums for the U.S. Navy, performing for historical dignitaries like Chiang Kai-shek and Haile Selassie while traveling the world with his Rolleiflex camera. Stationed at Treasure Island in the San Francisco Bay Area, Sonnabend haunted the North Beach jazz clubs and began painting. He gave the first painting he ever created to a fellow sailor, then decided he wanted the nude portrait of his “red-headed, epileptic girlfriend” back. “I left him 30 bucks for the frame he’d bought for it, but they still tried to give me a Captain’s Mast,” he says. “Instead of booting me out, [the Navy] just kicked me off the base and made me go live with that red-headed, epileptic girlfriend.”

As he finished out his time in the service, Sonnabend absorbed what remained of the fading Beat scene. He soaked up the frenetic poetry and sat in on pyrotechnic bebop sessions. “God, I tried to swing with them, but it was too fast for me. I was this uptight white boy. They left me in a cloud of dust. I always felt like I had to go home and woodshed afterwards,” he says. “The truth is, I missed out on all the real Beat years. It was all over by the time I got out of the Navy.”

The Great Kokoschka

Honorably discharged, Sonnabend studied painting at the University of Italy in Florence on the G.I. Bill. “My uncle wanted me to go to the Sorbonne,” he says. In Florence, Sonnabend continued to play drums, sitting in with local Italian jazz musicians. The jams coalesced into a formal group and, in 1958, they represented the city of Florence at the International Jazz Festival in Rome. He began dating a “serious Australian painter” who was furious when his “red-headed, epileptic girlfriend” painting was accepted into a juried show called American Painters in Florence. “She said the only reason I was in the show was because I was American, which was true,” he laughs. “Man, was she pissed.” When the great Austrian painter and writer Oskar Kokoschka admitted Sonnabend as a student into his summer workshop in Salzburg, it was the opportunity of a lifetime.

“That’s when I got spinal meningitis,” says Sonnabend. “No joke.” Without rapid treatment, meningitis could cause brain damage or death. Fortunately, Italian doctors had recently developed an effective serum, and Sonnabend received it quickly. The young artist remained determined to study under Kokoschka, but the meningitis had taken a toll on his body. The workshop began a week after his release from the hospital. “I was the only student in the class allowed to sit, so he made fun of me. On the first day, he asked me if I had measles. After that he’d always ask, ‘Ach, what new disease do we have today?’ The whole class would be laughing,” says Sonnabend. “But he was a great, inspirational teacher. In the beginning, I was his worst student—by the end, maybe his best.”

Kokoschka is remembered as a pioneer of expressionism and a self-proclaimed “martyr of the arts.” Disdainful of the rules and norms of art, the wildly talented Kokoschka’s work provoked and shocked throughout his career. His early nude drawings were deemed sexually violent; his depiction of the Holy Virgin, savage and dark. A short play, “Murderer, the Hope of Women” is considered the first Expressionist drama. His private life proved to be as dark as his work. Obsessed with Gustav Mahler’s widow, Kokoschka created a life-sized doll in her image. When the manufacturer couldn’t get details such as pubic hair to his exact specification, he destroyed the doll in frustration. The Nazi Party officially deemed Kokoschka a degenerate in 1934 and he was forced to flee to Prague.

By the time Sonnabend encountered the great artist in Salzburg, Austria, Kokoschka had been a naturalized British citizen for more than a decade, but continued to paint, write and teach. While some of Sonnabend’s paintings are reminiscent of his mentor’s style, the most important thing he gleaned from Kokoschka was a lifelong dedication to art. “He took us to a 300-painting retrospective of his work,” says Sonnabend. “It was such a major inspiration to see his whole lifetime of art in one place.”

Before returning to the U.S., Sonnabend happened upon Kokoschka sitting by himself, watching girls playing tennis. “Someday you’ll be sitting here just like me at 73 watching the girls play tennis,” Kokoschka told him. The moment has stuck with Sonnabend. “Now I’m 15 years older than Kokoschka watching girls play tennis,” he says in disbelief. “Incredible.”

Art Not Money

In 1961, the great artist Marcel Duchamp bemoaned the rampant commercialization of art. In his essay “Where Do We Go From Here?” Duchamp wrote that the great artists of tomorrow will have to live like ascetics and “go underground” to preserve the purity of their art. Sonnabend took Duchamp’s words to heart. “There is more artistic freedom in obscurity. Being criticized, shrunk or defined just slows you down,” he says. “The freedom to pursue art isn’t something any business or critic or fame can give you. You have to reach out and grab that for yourself. Protect it.”

Even Uncle Casey had betrayed the muse. He’d married a Romanian-American art dealer named Ileana Castelli. In 1962, the couple had opened the first Sonnabend Gallery in Paris to champion contemporary American art in Europe. By 1970, they would move the gallery to New York City, where it would remain at the center of the art world throughout the 1990s. Ileana and Michael Sonnabend have long been associated with an infamous art world conspiracy theory, according to Sonnabend. “They were paid by the CIA to open galleries and promote certain American artists in order to shift the center of the art world from Paris to New York,” says Sonnabend. “It’s well-documented.”

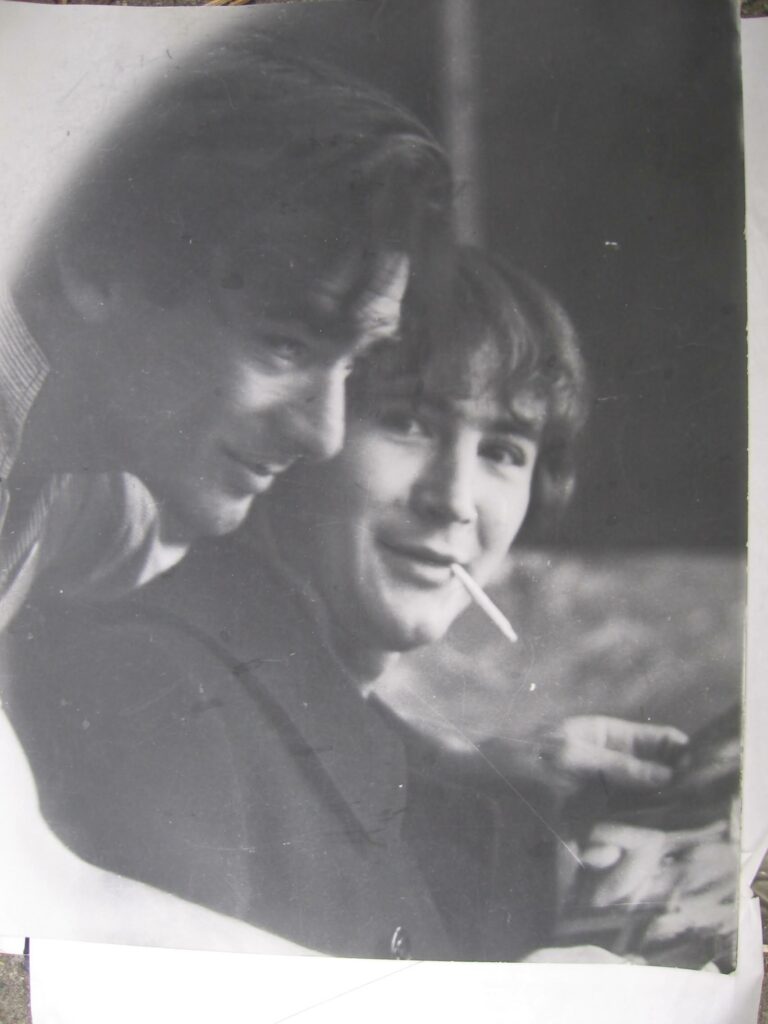

In 1962, the San Francisco Museum of Art gave Sonnabend a one-man photography show. The exhibit featured dreamy, poetic images of people he’d captured with his Rolleiflex around the world. “It was a huge honor for someone as young and unknown as me,” he says. “Other photographers would have cut off their nose for the opportunity.” Although some critics were skeptical of his technical skill, most responded with hearty acclaim. The critic John Coplans wrote, “Here is the work of a man with a poet’s eye. Intensely aware of human suffering, his photographs, skillfully composed, are without sentimentality. Quietly and with care they isolate and record a moment of penetrating vision.”

It should have been a triumph for the 29-year-old artist, but the experience left Sonnabend cold. “When my parents asked me if I’d ‘sold anything yet,’ it turned me off. It took the joy out of it,” he says. “So, I left while the show was still up. I didn’t want to bask in any of it.” Disenchanted, Sonnabend lit out on a spiritual quest with his camera, traveling through India, Pakistan, Turkey and Nepal with his camera. “I half-heartedly looked for a guru while taking some really good photos of gurus,” he says.

When Sonnabend returned to San Francisco from his travels, the “hippie thing was starting to happen.” He met a promising young poet named Stan Rice who’d married his high school sweetheart, Anne, and the three became fast friends, drunk on the power of words. Sonnabend continued to write and paint, but found himself drawn back to the drums. He still wanted to play jazz, but now rock was king. “I could play rock ’n’ roll in my sleep. It was so simple, like Dixieland,” he says. He backed up friends like the Kingston Trio and jammed with a litany of musicians, many destined for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

He played drums for Quicksilver Messenger Service in 1964, but found their rock ambitions frustrating. “They’d have these endless band meetings. If they didn’t want to jam, fuck it. I was out of there,” he says. His stories from these years are endless and wildly entertaining. He jammed with Mike Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield (“They were doing two-foot lines of coke at my pad,” he says.), collaborated with Yoko Ono in absentia, pissed off Janis Joplin by turning down her Ripple wine on Mount Tamalpais, jammed for Ravi Shankar and listened to David Crosby confess. “He said, ‘Casey, you’re not going to like the music I’m going to make, but I really want to buy a boat,’” Sonnabend remembers.

Meanwhile, Sonnabend’s own reputation among the countercultural cognoscenti was growing. In 1967, a photo of a sadhu he’d taken on the banks of the Ganges was used to promote the Human Be-In, the iconic outdoor gathering at San Francisco’s Polo Fields. Later that year, his work was prominently displayed at the Monterey Pop Festival, where Sonnabend watched rock bands bend over backwards for record deals. The hippies were as hypocritical as the rest, he concluded. The Monterey Pop Festival would be his last formal art show.

Pure Obscurity

Sonnabend went underground for good in the 1970s. He moved to Big Sur, grew weed, started playing “outside” jazz on piano and churned out artwork in complete anonymity. And then, in 1985, he met the love of his life, Anne—a woman 30 years his junior. The couple spent eight years together and had two children, but financial stress broke them apart.

“I understood. I didn’t hold it against Anne and Rick. She ended up having a 25-year marriage to a good buddy of mine. He was a very steady guy, so I was ok with it. Yeah, I lived in a van in front of the house, but I got to see my kids. She and I managed to stay best friends. People couldn’t understand it, but we made it work, although it wasn’t easy,” he says.

Today, Sonnabend is experiencing something of a personal renaissance. Fresh off double bypass heart surgery, he lives in a retirement home in Freedom thanks to the Veterans Administration. He looks and feels better than he has in years. He’s creating new work, jamming with friends and telling stories, always telling stories. He’s also—miracle upon miracles—back together with Anne after nearly 30 years apart.

“She and Rick broke up a couple years ago,” he says. “I was still carrying a torch for her and now we’re back with a vengeance. It’s like our third honeymoon. She just needed to be worshipped, and who better than me? I have no competition in that department.”

A grandfather many times over, Sonnabend stays in contact with a large extended family scattered across the West Coast. In addition to his two children with Anne, Sonnabend has three more children from previous relationships. “I have children aged 30 to 60,” he says. “We all stay in touch.”

So, after all these years, isn’t it time to show the artwork? Isn’t it time to crack open the storage space in Marin and sift through all that cultural treasure? Isn’t it time to rediscover the photography?

“Come on, man,” Sonnabend says with a sigh. “Haven’t you been listening? I don’t have time to curate some fucking art show. I have things to do. There’s still fun to be had. I’m in love!”

One correction, if I may…Anne Rice was not a benefactor of Casey’s. It was her husband that loved Casey and his work and who kept him in paint and canvas with a roof over his head for several years.

A five-WOW!!! story — (forget stars) — and immediately after exclaiming then, I had to read the whole thing aloud to my wife.

A joy to read an author capable of capturing what would remain an enigma to most; the choice to commit to living life to its fullest based on a personal world philosophy; instead of a preeminent fixation on money.

Kudos to you & to Casey/Michael/Isaac.

I rented a room in the house in west Santa Cruz around 1987-89. At the time Casey had this garage full of paintings. I was a 25ish kid working in a psychiatric hospital. I would hang out with Casey, look at his art and listen to his wild stories.

He has been an inspiration for me my whole life. It’s so great to see this acknowledgment of the creative genius who has inspired me so.

I met Casey around that same time. Did you ever visit our house on Columbia St near Pelton? You’d remember our big black lab Bogie. Lol

I beg to differ with Wag Weiser. I corresponded with Anne Rice when Casey needed money. I have those emails. Anne did help Casey. In fact, Casey told me that the three of them had made a pact with each other. Whomesoever made it big would share the money with the others. While Casey, a complainer imo, didn’t think Anne lived up to this pact; she did when I asked her and then Wag reports, so did her husband. BTW Casey was only too happy to sell paintings to me – he needed money, of course. My mother was a painter, when she died I gave Casey most of my mother’s brushes and her easel. Artists help each other.

I lived around the corner from him in the late 80s on the Westside of Santa Cruz, and he’d come over all the time, tell us wild stories that all turned out to be true, and hang out and jam with me and my early 20 something friends in our garage studio at a house we dubbed Lumbo. It began a 35 year friendship that’s lasted to this day. Casey’s presence has been a huge blessing in my life. I also have quite a few of his paintings and scribbles. Lol. I’m glad he’s finally getting some press. He greatly deserves every bit of it.

I remember this guy, if only he’d been more responsible for himself he would have developed more as an artist and person. His pride in not having or wanting to work was not an asset, it was in reality a burden on others.