Since its 2020 debut, the Deep Read has featured Margaret Atwood, Tommy Orange and Yaa Gyasi. How do you top a trifecta like that? The annual program, put on by the Humanities Institute at UC Santa Cruz, approached the selection of its 2023 book by going in a different direction. There had already been three novels, so it was time for something different. Program Coordinator Laura Martin told me the committee’s choice, Elizabeth Kolbert’s Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future, was unanimous.

Not only does Under a White Sky mark the Deep Read’s first foray into non-fiction, but it’s also a work of science journalism.

Not including the afterword, the book is 201 pages. Kolbert’s vibrant and descriptive reporting and her dark-humored reflection pull you into the field alongside her. While Under a White Sky is a quick read, it resonates with you for a long time. And while it resonates, the complexity of the themes Kolbert presents surrounding climate change and human intervention inspires a deeper dig. Kolbert jumps from place to place like a squirrel hopping from branch to branch. She first takes us on a leisurely cruise on the Chicago River, where she refers to Joseph Campbell’s Heart of Darkness.

It might seem like an unusually bleak metaphor during what’s supposed to be a pleasant, touristy boat ride, but Under a White Sky is an endless journey into the unknown, and there’s no turning back. Once humankind starts messing with something, we can’t simply walk away and expect everything to go back to how it was before we mucked it up.

For decades, the Windy City has been trying to solve problem after problem that arises in its river, employing possible solutions that only end up causing new problems, which in many instances are worse than the initial complications—Kolbert refers to the river’s Sanitary and Ship Canal as an “Oversized Sphincter.” One tactic involved bringing in vats of Asian carp, which planners thought would help ingest the massive amounts of bacteria from the river, which supplies Chicago with drinking water. But the non-native carp had no predators, so the Chicago River has become infested with the fish—the solution: electrifying areas of the river that would kill off some of the carp. As you can imagine, it wasn’t the best idea.

The falling domino effect of these infrastructure-meets-nature dilemmas exists worldwide, and Kolbert takes us along as she details several. All follow a similar pattern that involves humans.

“You can’t prepare for a future you can’t imagine,” Kolbert says. “The trouble is, it’s hard to picture the future we are creating. As the climate swings of the past suggest, even subtle and gradual forces—tiny variations in the Earth’s orbit, for example—can have world-altering consequences. And what we’re doing now is neither subtle nor gradual. In little more than a century, humans have burned through coal and oil deposits that took tens of millions of years to create.”

Kolbert takes us to an Australian lab where students are working through the night, mixing corral sperm with eggs in bowls—making a lot of sperm jokes along the way—attempting to figure out how to rejuvenate the Great Barrier Reef, which has been dying off.

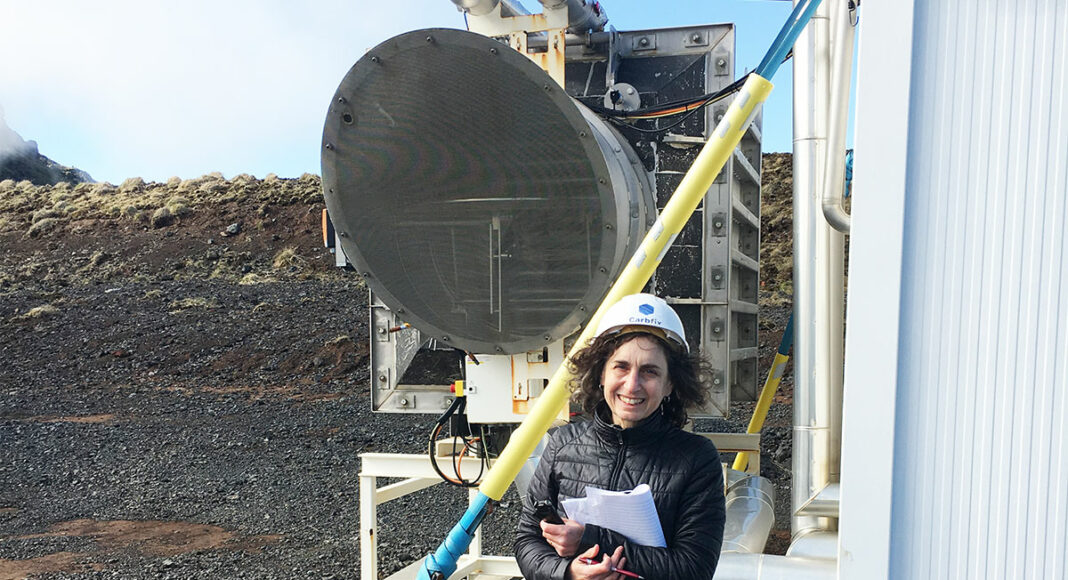

Meanwhile, in southern Iceland, Kolbert visits Climeworks, a startup that scrubs carbon emissions from the sky and essentially converts the pollution into rock using a system inspired by the effect volcanic lava has on CO2. Then these two-foot rock cylinders are buried in the ground. While carbon dioxide removal is essential, the amount of money it would cost to impact slowing climate change is so large it’d never be feasible.

“For the last 30 years—more if you go back to 1965—we have lived as if someone, or some technology, were going to rescue us from ourselves,” Kolbert says. “We are still living that way now. [Climate Change] isn’t going to have a happy ending, a win-win ending, or, on a human timescale, any ending at all. Whatever we might want to believe about our future, there are limits, and we are up against them.”

post-Covid society.

Kolbert’s time in Louisiana, where she explores the rising seas inundating the Mississippi Delta, which leads to the area south of New Orleans essentially breaking off into the Atlantic, hits home.

“If Delaware or Rhode Island had lost that much territory,” Kolbert writes, “America would have only 49 states. Every hour and a half, Louisiana sheds another football field’s worth of land.”

Kolbert notes that every coastal city is like New Orleans, committed to living in what’s pretty much a place that people should have never lived in. However, no matter the cost, financial or human, it’s impossible to convince residents to abandon their homes. I connected to the flooding in Pajaro and the levee breaches that have been going on since 1955, just six years after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the Pajaro River levee system—it also breached in 1958, 1995 and 1998. Most recently, on March 10, 2023, multiple breaches led to flooding that impacted ag land and Hwy 1, which had to be closed for several days.

I asked Kolbert how she’d approach the reporting of the Pajaro River levee; there are so many angles: the science, politics, socioeconomic ramifications, etc. How do you separate emotion and frustration from science?

ELIZABETH KOLBERT: That’s a really good question. As a journalist, you are always confronted with that, I suppose. I don’t see it as different in some ways from reporting on a lot of other problems in the world. But I think that’s what distinguishes some of the subjects that I already read from your typical journalistic disaster stories that people cover. The inexorable nature of climate change as you alluded to earlier. We’re not going to stop sea level rise at this point. That’s really not possible. So, we will be dealing with the consequences of climate change forever. And that’s a heavy number.

Any story has a lot of angles, and it is completely embedded in politics and economics. I should also add that those two are intimately related as well. In Under a White Sky, I try to look at these proposed or, in some cases, actual interventions that are designed to sort of counteract previous interventions. I tried to look at them on their own terms and not get into the many, many, many political ramifications they all have; that would have been a book that is simply too humongous to write. And this is a very pointed book; it’s trying to make a point succinctly.

Anthropocene is the buzzword of the book. How would you define it?

It refers to the idea that humans have become the dominant force on the planet. So, we are now geological; our activities shape the earth and its future on a geological scale.

When humans began messing with everything, for better or worse, you say that’s when it became the point of no return. Nothing will ever return to how it was before, so we can’t simply walk away and hope for the best. We must continue to tinker, or things will just get worse.

I think the book lets you draw your own conclusions on that. I think what it’s identifying, what it’s really looking at is our tendency or our reluctance to go back and, in some cases, as you say, the inability to go back. There are simply too many people on the planet right now to just stop doing what we’re doing. And so, we are sort of compelled to continue.

In 201 pages, you report everywhere, from Chicago to Australia to Death Valley. It seems like it could be random, but it’s very intentional. Did you start with an outline? How did you connect the dots, like the story of the carp in the Chicago River to the Mojave pupfish?

The first story I reported on was in the middle of the book about the coral reef, and then the other stories, in some cases, found me. In other cases, I went looking for them.

Out of all the stories in Under a White Sky, what was the most complex for you to understand before writing about it?

Good question. I’m trying to think. You know, most of them are pretty straightforward, I guess. The most complicated science is actually in the carbon removal chapter, which is a chapter in which I go to Iceland. So that was probably the most difficult to master the subject matter, if that makes sense.

Hubris is a recurring theme in Under a White Sky. I think it’s a recurring theme in most science, especially when we get into gene editing and geoengineering. On many of the recent podcasts you’ve appeared on discussing your book, hubris is brought up with a negative connotation. Would you say that’s a fair assessment—hubris’ association with science is a negative attribute?

I certainly would. I think we see it playing out all the time now. Hubris is a good word, and heedlessness is another good word. We just plunge ahead without thinking through the consequences on a humongous scale. And then, even when we’re warned about the consequences, even when the consequences are overwhelmingly apparent, we are very reluctant to change the way we do things. And that’s rooted in psychology, it’s rooted in the economy, it’s rooted in politics, but it’s going to be the end of the world as we know it.

Is there anything you reported that meant a lot to you but didn’t make it into Under a White Sky?

No, not really. I did get to see one really interesting experiment—it was going on in the Australian Outback, and it didn’t make it into the book for complicated reasons. But most of the things I set out to report on for the book made it. You don’t have—maybe some people do—much luxury of going out and doing a tremendous amount of reporting and just leaving it on the cutting room floor. So, I didn’t do that for this book. I’m happy to say.

As you were reporting and writing the book, did you have any unexpected epiphanies as everything was coming together?

The point of the book is this pattern that I started to see everywhere; that’s sort of what motivated the book. I would not say there was exactly an epiphany, but I would say that I have continued to see that pattern everywhere. I constantly am coming up against new instances where people’s responses are, “Well, things are kind of messed up because of our actions, and we’re going just to have to take more actions to unmess them up.” I keep seeing that pattern.

I want to talk a little about your style of journalism. I’d almost say it’s your trademark, the way you describe the physical attributes of all of your sources when they are introduced. Has this always been something you’ve employed?

I think my style is definitely influenced by having worked for many years for The New Yorker, which doesn’t really have pictures. You have to give your reader a picture in words of what you’re looking at, who you’re talking about.

You’re often lumped into the “New Journalism” category alongside Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, Hunter Thompson and others. New Journalism has always been difficult for me to grasp because I don’t see any other way of effectively relaying information of value to readers. What are your thoughts on the term New Journalism?

Honestly, I think it was a useful term back in the ’70s when it was [still relatively new]. We’re all sort of practicing the New Journalism now. We’ve lost the old journalism, which was a much more staid and sort of stolid reporting where the idea was writing from a particular position of often anonymity. You’re just the filter for the information. Then people like Tom Wolfe and Hunter Thompson came along and became characters with this tremendous amount of voice in their work. That was the New Journalism; we’re all in their shadow now.

Are you currently working on anything?

I don’t have another book in the works. I’m sort of toying with some things, but there’s nothing I want to talk about right now. Sorry about that.

Elizabeth Kolbert will be in conversation with podcaster Ezra Klein on Sunday, May 21, at 4pm. Free. Seating is first come, first served. UC Santa Cruz Quarry Amphitheater, 1156 High St., Santa Cruz. thi.ucsc.edu/deepread