A year ago, almost to the day, I had the rare opportunity to sit down with Dr. Christopher Gardner, Stanford professor and one of the country’s most respected nutrition scientists.

Gardner was among the 20 independent nutrition science experts who comprised the Advisory Committee tasked with crafting the recommendations for the 2025–2030 USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans. This rigorous, nearly two-year process is designed to translate the best available science into practical guidance for a nation.

The members of this elite Advisory Committee are carefully selected for ties to government or to the food industry. Members go through extensive background checks on financial, ethical, legal, and criminal conflicts of interest. During the review of the scientific evidence and development of the report, committee meetings were livestreamed for full transparency. The public was also given opportunities to provide comments, which were considered.

As Gardner told Good Times in 2025, “The committee scrutinized hundreds of studies before determining that eating patterns which include plenty of legumes, vegetables, and whole grains consistently deliver the best health outcomes.”

What made this most recent Dietary Advisory Committee notable was that its conclusions, particularly around plant-forward eating, made it into the highly influential 10-page Executive Summary. Historically, when protein-rich foods were listed, meat and poultry led the charge, with beans and lentils relegated to the fine print.

This time though, the committee recommended flipping that order, placing plant-based proteins first. It was a meaningful shift, and no small feat. Thus the conversation with Dr. Gardner, which took place shortly after the Advisory Committee dispersed, was one of optimism. The final recommendations, compiled into the Summary, seemed like a step in the right direction when nationally, rates of diet-related disease continue to skyrocket.

But a lot can happen in a year.

The final review

The Executive Summary then advanced to the USDA, where it was reviewed and revised by a team of experts appointed by U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins. When the final Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030 were released, many of the advisory committee’s plant-forward recommendations were sidelined.

This decision to ignore the Executive Summary is explained in the 90-page report (publicly available online) as a “shift from corporate-favored advice to science-backed recommendations for better public health, focusing on ‘real food’”.

Meanwhile the names of the USDA-appointed committee members and their ties to industry, including National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, National Dairy Council, General Mills and the National Pork Board are plainly listed.

Local advocates such as Eat for the Earth Executive Director Beth Love raised concerns about conflicts of interest among reviewers with ties to meat, dairy, and low-carb commercial programs. Whether intentional or not, the resulting guidance reflects a familiar American pattern: animal products elevated, plants negotiable.

Take the USDA’s top recommendation to “prioritize protein at every meal.” This is not a commentary on the importance of protein. It supports muscle maintenance, satiety, and blood sugar balance. But without context, the advice risks crowding out fiber-rich plant foods, which is especially troubling when roughly 95% of Americans already fall short on fiber intake.

Institutions take notice.

The Harvard School of Public Health released a critique of the increased recommendations for red meat and dairy, as contradicting “extensive evidence on their links to negative health outcomes, as noted by Harvard’s own nutrition experts.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Gardner issued a careful analysis of the report, stating, “Despite carrying forward familiar themes, the guidelines fall short of translating nutrition science into clear, coherent, and equitable guidance.”

Among the detailed breakdown of the new guidelines, Gardner writes, “Protein is overemphasized, while fiber is downplayed. The guidelines place a strong emphasis on protein intake, despite robust evidence that shows most Americans already consume sufficient amounts. The proposed protein targets are difficult to meet without exceeding recommended limits for saturated fat and sodium”.

In reality, Americans are eating roughly twice as much meat as we did several decades ago. The rise of diet-related disease over the past century closely tracks the rise of factory-farmed meat, not because meat itself is new to the human diet, but because how meat is produced, processed, and consumed has fundamentally changed. To be sure, low-cost, readily available meat isn’t the only change that has impacted our rising disease rates, but it’s one worth taking a closer look at.

From Farm to Factory

For most of human history, meat was eaten occasionally, in relatively small portions, sourced from pasture-raised animals, and consumed as part of meals dominated by plants. After World War II, industrial agriculture transformed meat into a cheap, abundant, daily staple. Government subsidies, feedlots, antibiotics, and confinement operations dramatically increased supply while driving down cost. Portion sizes ballooned. Meat moved from side dish to centerpiece.

Modern industrial meat differs from its historical counterpart in important ways. Grain-fed animals produce meat higher in saturated fat. Routine antibiotic use contributes to resistance and microbiome disruption. Processing often adds sodium, preservatives, brines, and seasoning solutions. Ultra-processed meat products, deli meats, fast food, and frozen meals became dietary staples.

Not coincidentally, this shift parallels rising rates of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and certain cancers, particularly colorectal cancer. Large epidemiological studies consistently link high intake of red and processed meat, especially factory-farmed and heavily processed forms, to increased disease risk. Processed meats show the strongest and most reliable associations.

The displacement effect

One of the most overlooked effects of increased meat consumption is known as displacement. Diets high in factory-farmed meat tend to be lower in fiber, legumes, whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. When meat crowds out plants, gut health suffers, inflammation rises, and metabolic resilience declines. This helps explain why populations that eat less meat but more plants, Mediterranean and Blue Zone cultures in particular, experience lower rates of chronic disease and longer, healthier lives.

The issue isn’t an occasional steak or culturally traditional meat consumption. It’s the daily normalization of large portions of cheap, industrially produced meat. In traditional food cultures, meat adds flavor rather than bulk, is paired with vegetables and grains, and is eaten mindfully and socially.

Seen this way, diet-related disease didn’t rise because humans suddenly started eating meat. It rose because food systems shifted toward speed, scale, and profit, disconnecting food from ecology, culture, and health. The most consistent solution across decades of nutrition research isn’t elimination, it’s rebalancing: less factory-farmed, processed meat; more whole, minimally processed plant foods; better sourcing, smaller portions, and greater intention.

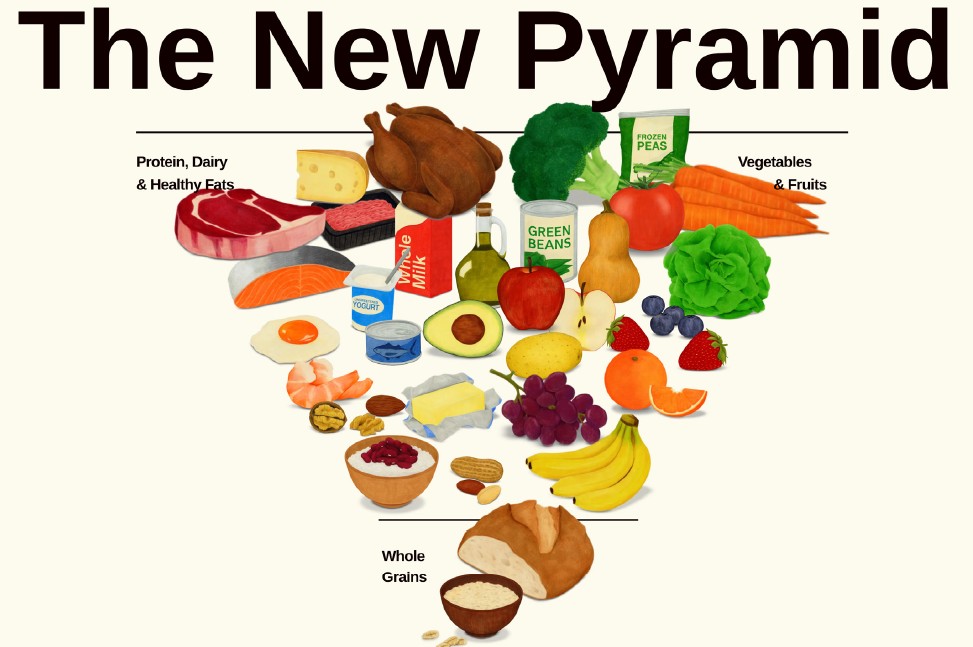

A more grounded, Mediterranean-style approach might sound like this: include a source of protein at most meals, build meals around whole foods and variety with protein as a supporting player, and aim for enough protein across the day rather than perfection on every plate. In practice, that could look like beans in soups, yogurt or tofu at breakfast, fish alongside vegetables and whole grains, or hummus and nuts as snacks.

Milk-drinking cultures: mixed outcomes

Second on the list of new recommendations, the advice to prioritize full-fat dairy also raised eyebrows. Even the American Heart Association issued a carefully worded concern, noting that such guidance could unintentionally increase saturated fat intake, a known driver of cardiovascular disease.

Globally, the relationship between milk and health is far more nuanced than the long-standing message that dairy is essential for strong bones. Many of the world’s healthiest, longest-living populations have traditionally consumed little to no cow’s milk. East Asian cultures historically had low dairy intake yet low hip fracture rates until Western diets took hold, relying instead on leafy greens, calcium-set tofu, sesame seeds, sea vegetables, and small fish eaten with bones.

Mediterranean regions consume modest amounts of yogurt or cheese, not large glasses of milk, and consistently show low cardiovascular disease rates and high longevity. Blue Zone communities–areas known for long life spans–such as Okinawa, Ikaria, and Nicoya, consume dairy minimally, if at all, yet maintain strength and mobility well into old age.

In these cultures, bone health is supported by regular weight-bearing movement, adequate vitamin D from sun exposure, high intake of fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole foods, and lower consumption of ultra-processed foods.

By contrast, countries with the highest milk consumption, the U.S., Canada, Northern Europe, and Australia, do not consistently show better health outcomes. Hip fracture rates are often higher, as are rates of cardiovascular disease, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Large cohort studies have found no clear protective effect of milk on fracture risk, and in some cases, higher milk intake is associated with increased mortality, while fermented dairy shows more neutral or modestly beneficial effects.

This doesn’t suggest drinking milk is harmful, but it does challenge the idea that it’s necessary.

When I lead workshops, the most common refrain I hear is, “Nutrition advice is always changing.” And it’s true, if you’re paying attention to headlines, influencers, and algorithm-driven wellness trends, it can feel impossible to keep up. One week fat is the villain, the next it’s carbs, then protein, then seed oils, then sugar in fruit. But when we zoom out, the big picture hasn’t shifted nearly as much as the noise would have us believe.

The Mediterranean Diet and the diets of Blue Zone populations have remained remarkably consistent for centuries. Long before nutrition science, tracking apps, or supplement aisles, these cultures were quietly producing the best outcomes we know of for longevity and disease-free living. They did so without factory farming, ultra-processed foods, or a reliance on expensive interventions. Instead, the emphasis was on fresh, local food, shared meals, seasonal eating, and enjoyment, rather than counting grams of nutrients or calories.

For those new to these terms, both the Mediterranean Diet and the Blue Zones framework were coined in response to researchers noticing something curious: certain populations around the world were living significantly longer, healthier lives than those of us in the United States. When scientists studied these populations more closely, patterns emerged—not just in what people ate, but in how they lived.

The Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean Diet is less a rigid plan and more a pattern of eating shaped by geography, culture, and tradition. It centers on vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and olive oil as the primary fat. Fish and seafood appear regularly, while meat, especially red meat, is eaten sparingly. Meals are often simple, built from a handful of high-quality ingredients, and enjoyed slowly.

What’s often missed is that this way of eating evolved out of necessity, not optimization. People ate what was available locally and seasonally. Food was prepared at home, often from scratch, and meals were social. Wine, when included, was modest and typically consumed with food. There was no obsession with perfection, just consistency over time. The result? Lower rates of heart disease, diabetes, and many chronic conditions that plague modern Western societies.

The Blue Zones Diet

The Blue Zones Diet comes from studying regions such as Sardinia, Italy, Okinawa, Japan, Ikaria, Greece and perhaps more surprisingly, Loma Linda, California. All represent places where people routinely live into their 90s and beyond with high quality of life. While the foods vary by region, the similarities are striking. Diets are overwhelmingly plant-based, with beans and legumes as staples. Animal products are used sparingly, often as flavor rather than centerpiece. Processed foods are virtually absent.

Equally important is what’s not present: calorie tracking, protein targets, “superfoods,” or biohacking protocols. People eat enough, stop when they’re satisfied, and maintain stable weights over decades, not through restriction, but through rhythm. Members of these societies are not known for asceticism, denying themselves the good stuff to look good on Instagram. Instead, these regions are known for the deliciousness of their cuisine.

Case Study: Loma Linda, California

One of the most fascinating real-life examples is Loma Linda, California—home to a large population of Seventh-day Adventists and the only recognized Blue Zone in the United States. Despite living in the same broader food environment as the rest of the country, this community experiences significantly lower rates of heart disease, cancer, and obesity.

Why? Their dietary patterns closely resemble those of other Blue Zones: mostly plants, minimal processed food, modest portions, and regular meal routines. Many Adventists are vegetarian or plant-forward, but just as important are shared meals, regular movement, strong social ties, and a built-in rhythm of rest. Their health outcomes remind us that culture can be more powerful than convenience, and that longevity is not a mystery reserved for faraway places.

Rather than reducing food to a set of numbers, these communities use it as a source of celebration, connection and community. Maybe that’s what’s missing in our complicated food culture? Or perhaps we’ve sacrificed all of that for efficiency, and in the process, are left satiated, but still somehow unsatisfied.

Diet Is Incomplete

Both the Mediterranean and Blue Zones Diets are short-changed without acknowledging the lifestyle that is inseparable from the diet itself. These cultures do not revolve around calorie counting, macro tracking, or external notifications of when and what to eat. The mind-body connection is reliable enough. Movement is woven into daily life through walking, gardening, cooking, and manual tasks. Rest is respected. Stress is buffered by the community. Meals are not rushed or eaten alone in cars.

This is a critical distinction. In the U.S., we’ve attempted to extract diet from context and turn it into a product, something to optimize, purchase, and control. In doing so, we’ve made eating far more complicated than it needs to be. And far less enjoyable.

So the question becomes: why has nutrition in the U.S. become so confusing? Humans have been eating for a very long time, and the data on what works is already in. Resources like the Harvard School of Public Health, and US News and World Report’s annual list of expert-recommended diets are free and unbiased sources of information that all point to the same basic principles.

But is this where we get our nutrition information? Rarely. Instead, our attention is pulled this way and that by our devices as the latest “diet news” beckons. When nutrition science starts to feel overwhelming, it’s worth asking a simple question: Who benefits from providing this new recommendation? If the answer is commercially biased, delivered by an influencer or ad, the answer is, probably not you.

Because at the end of the day, the quiet wisdom of “mostly plants” still holds true, but so does slowing down, sharing meals and reclaiming the time-honored joy of simply delicious food.