Deadheads didn’t invent taping concerts. As Clinton Heylin chronicles in his exhaustive 1994 book, Bootleg: The Secret History of the Other Recording Industry, people have been making unauthorized recordings of live music since the dawn of recording technology. Using crude wax cylinder recording devices, audience members were “bootlegging” live opera performances as early as 1901.

But fans of the Grateful Dead took the practice to a new and previously unimagined level in their documentation of the group’s concert history. At first, concert tapers had to be sneaky, but by late in the Dead’s historical arc, they were acting with the tacit approval of the band.

Now, Mark A. Rodriguez has brought together the various components of this underground tradition in his new book, After All is Said and Done: Taping the Grateful Dead 1965-1995. A massive tome–nearly LP-sized, more than an inch thick and weighing in at close to four pounds–Rodriguez’s book represents 12 years of dedicated and exhaustive research. A breathtakingly impressive work, After All is Said and Done represents the kind of creative fanaticism that could only come from a Deadhead.

Loving Sculpture

The casual observer might look at the hefty, pale-yellow hardbound volume and see a book. But Rodriguez prefers to think of it as merely one of several physical manifestations that make up the project.

“I work conceptually on a project-by-project basis with many different materials,” Rodriguez explains. Those materials, he says, can involve “anything related to three-dimensional space.” And he considers the work to possess a performative dimension. Rodriguez says that his decade-plus focus on the project “involved a lot of relating to people socially to collect tapes, to discuss tapes and to get certain information.”

The tapes themselves are at the heart of Rodriguez’s project. As Stuart Krimko asserts in one of the book’s many essays, Rodriguez “was struck with the Sisyphean impulse, perhaps familiar to many completist Deadheads, to acquire a copy of a tape of every show the band ever played.” Most estimates place that number somewhere in the neighborhood of two thousand recordings. Nobody knows for sure.

And as Krimko explains, since Rodriguez was already “an active artist with a conceptual bent, it wouldn’t be a mischaracterization to call the idea itself an artistic proposition.” And that’s precisely what the author of After All is Said and Done proceeds to do.

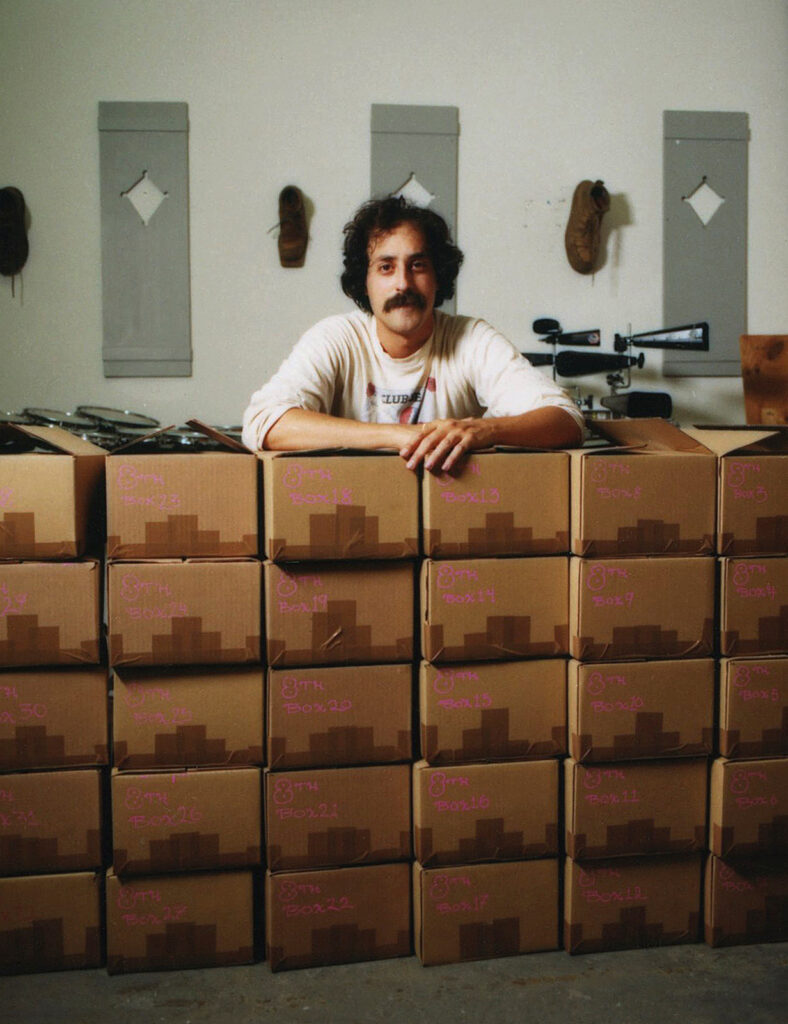

Rodriguez characterizes the result of acquiring, organizing and archiving his collection of live Dead tapes as “what technically might be called a relief sculpture with an additive process.” By way of explanation, he points to several images near the beginning of After All is Said and Done which document his collection. To the rest of us, those photos look like huge, wall-mounted shelving units filled with thousands upon thousands of cassette tapes, each meticulously labeled, and all placed carefully in chronological order. To Rodriguez, they’re documentation of the art project he’s shaped.

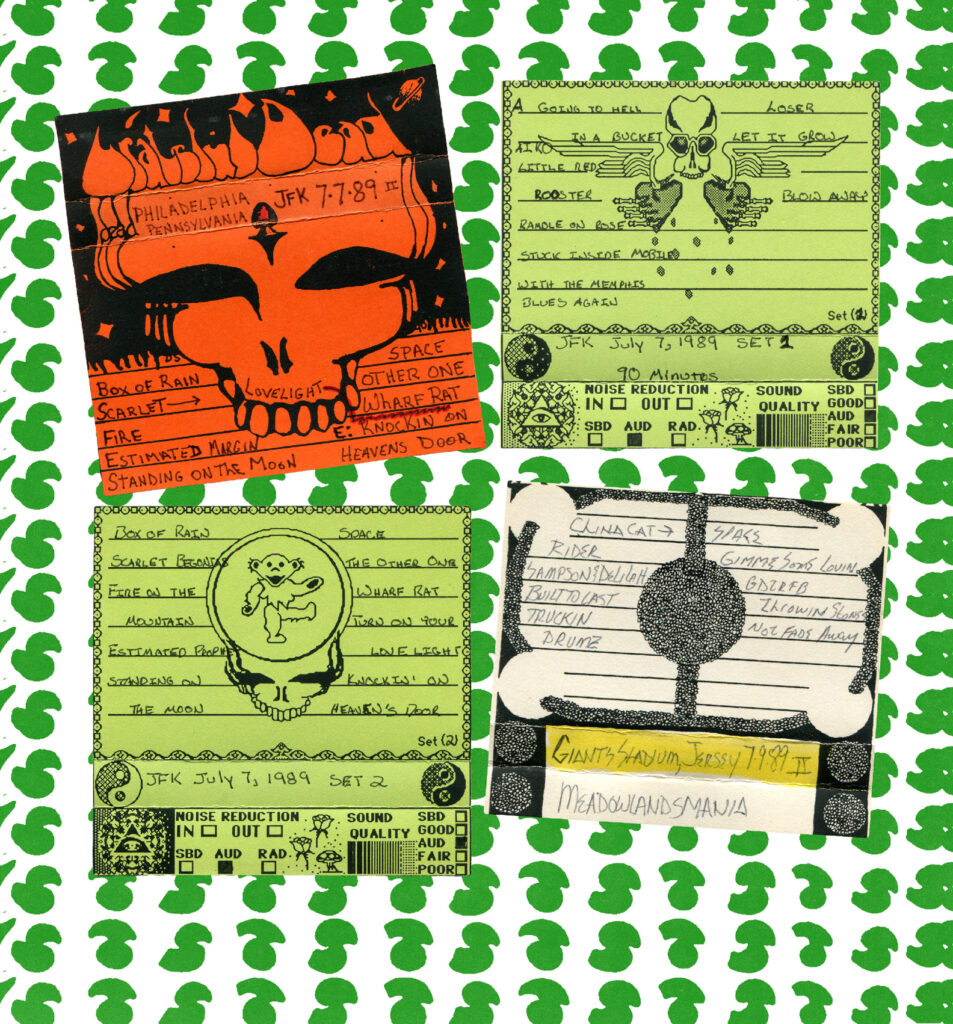

There’s also the music, of course: magnetic tape capturing audio documents of the Grateful Dead onstage in all their often-erratic, sometimes transcendent glory. But the history as compiled and archived by Rodriguez also emphasizes the project’s visual aspects. These visuals are not, except in a few rare cases, photos of the band. More than 150 pages of After All is Said and Done are filled with color photos of cassette j-cards–the paper sheets upon which loyal Deadheads have inscribed not only the set lists (with plenty of “>”’s to denote those occasions when one piece of music tumbles imperceptibly into the next), but also hand-drawn artwork, fancy lettering and additional annotation.

Often the j-cards contain information relating to the tape’s generation (meaning the number of analog copies between the source tape and the one in hand) and the occasional personal note (e.g. “My favorite #1 show of old-school Dead,” written on the j-card for a 1977 show at San Bernardino’s Swing Auditorium).

When photos of band members are included on the cards, as often as not they’re of Deadhead main man Jerry Garcia, hunched over one of his distinctive electric guitars, perhaps outfitted in some bright red knee-length shorts. Bobby Weir shows up now and again, but far more common are meticulously drawn human skulls–lots of skulls–and roses and dancing bears, plus co-opted images from pop culture (Mickey Mouse, Calvin and Hobbes, Bloom County etc.). Taken together, these j-cards represent both the crowd-sourced character of the entire taper enterprise, and its fundamentally communitarian character.

Yes and No

Rodriguez made sure to maintain an open mind while researching for the book, but he admits that he began with at least a vague thesis. “I was trying to figure out if the members of the Grateful Dead intentionally sought to reinforce that taping was good,” he says.

The answer to that question remains a bit vague. Even now Rodriguez wonders: “Was the taping phenomenon such a part of myth-making that it became a legacy? Or did [the Dead] not really have any control over it?”

While the Grateful Dead organization was involved in the project to the extent of allowing reproduction of specific images, no former members of the band were among Rodriguez’s list of interviewees. So he’s left to draw conclusions based on interviews with some of those who were around the band, and fellow expert Deadheads.

Rodriguez emphasizes that Grateful Dead Productions was cooperative, and he’s appreciative. Because of the multiple levels of red tape and multiple entities who had to sign off, it sometimes took him years to get clearance to include a particular image or document. Cases of flat-out “no” were rare—but there was one. After All is Said and Done includes photos of the San Rafael tape vault, and another in Nevada. Rodriguez hoped to include a photo showing the Grateful Dead tape vault that exists at Warner Brothers Records, the group’s label from the beginning to 1973. When he asked, the answer was a “hard and fast ‘no.’” So he decided that the next best thing would be to include a reproduction of the “no” email from Warners.

“I got shut down on that, too,” Rodriguez says with a wry laugh.

The Next Best Thing

Remarkably, Rodriguez never witnessed the Grateful Dead live on stage. “I was in elementary school when they performed last,” he admits. But he has frequently attended shows by the myriad post-Dead mutation –“Phil Lesh and Friends, RatDog and all that,” as he puts it–beginning in the 1990s. So for him, the tapes also serve as a way to reacquire that you-are-there vibe in the present day.

But for this expansive project, Rodriguez went straight to the source. Days before the pandemic-spawned global shutdown, he visited the official Grateful Dead Archive at UCSC. He sought to connect with the archivists and librarians there, hoping to gain access to “the documents that specifically lent themselves to the start of the official tapers section in 1984.”

He succeeded on that score, and the visit helped chart the project’s subsequent path. Rodriguez interviewed key figures connected to the Dead’s taped legacy, including Dave Lemieux, the Dead’s current archivist. He also spoke with archivist David Ganz, who was “kind of confused [as to] why I was interviewing him,” says Rodriguez with a chuckle.

Each interview and review of documents felt like a step forward on Rodriguez’s journey of discovery. “I took what I learned from someone–maybe based off documents I found from the archives–then found the line that would connect me to the next person,” he says. “It was an organic process, a weird detective thing. Kind of like forensics, in a way.”

The reader of After All is Said and Done experiences the journey in similar fashion. “For the most part, all the interviews are laid out chronologically as I [conducted] them,” Rodriguez says.

While there’s a kind of linear flow to the book, Rodriguez is keenly aware of the spontaneous, free-flow mindset that is often brought to all things Dead. “I wanted the book to be this experience where you could open it to a page, maybe half-complete it, and still come away with some curiosity,” he says. “Even though you might not understand the total context.”

Some of the documents that Rodriguez uncovered are reproduced in the pages of After All is Said and Done. Readers may experience a bit of cognitive dissonance upon reading the typewritten minutes of a meeting (dated July 11, 1984) at which the attendees included “M. Hart, P. Lesh, B. Weir, R. Hunter, J. Garcia, Ram Rod” and two dozen others. Business meetings aren’t the first thing that comes to mind when one thinks of the Grateful Dead, but such documents help explain the band’s collective attitude toward fan taping, and the ways in which the Dead organization’s perspective on the phenomenon changed over time.

Complete As Can Be

It’s not as if Rodriguez is any kind of a newcomer to the Grateful Dead and their work. “I’ve been researching the Grateful Dead in whatever capacity I could since I was 14,” says the 40-year-old author. And while images provide much of After All is Said and Done’s appeal, it’s much more than a picture book for the Deadhead’s coffee table. It’s filled with informative essays that round out the taper experience/phenomenon from most every angle.

“I wanted to add information that either wasn’t compiled in a succinct kind of way, or provide information that maybe didn’t exist before,” he says, noting that doing so posed a challenge. “That’s kind of a hard thing to do with the Grateful Dead,” he admits, “because so much information is out there.”

Still, there are holes in the larger narrative, especially when it comes to the band’s live onstage legacy. “The ’60s portion of their career is not as heavily documented,” Rodriguez explains. “There’s not nearly as much Pigpen-era material out there.” The Grateful Dead’s original keyboardist, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, was a founding member who was with the group through mid-1972.

Even the official Grateful Dead vault is ostensibly complete only from 1971 onward, Rodriguez says. Still, he holds out hope that there remain gems yet to be discovered. “There’s probably reel-to-reel tape that’s mislabeled or that can’t be identified,” he suggests. But nearly as quickly, he tamps down expectations. “Those are [probably] partial recordings, and the quality of tape is probably terrible.”

For all of his extensive efforts, even Rodriguez has yet to compile an exhaustive archive of Grateful Dead recordings. “I’m still 160 or so tapes away from completing the whole collection of recordings between 1965 and 1995 that are on tape,” he admits.

The live tapes documenting points on the Grateful Dead’s arc can be enjoyed and appreciated on multiple levels; After All is Said in Done is evidence of that. The music and the homemade physical packaging that accompanies the tapes are both substantial parts of the experience. Unsurprisingly, Rodriguez takes things beyond all that. These days he tends to focus on the quality of the recordings.

“I appreciate the music,” he emphasizes. “But I appreciate the method of recording, and the existence of the actual tape that I’m listening to at any particular time.” He feels there’s often something special captured on audience tapes, a quality that more polished and professionally created recordings can lack.

“Sometimes, if it’s a soundboard, I’m like, ‘Eh, this is boring,’” he admits. “Because the sound is so boring.” He believes that a tape made by an audience member can provide “an image of the concert [itself].” One can hear ambient noises–talking, applause–“but you’re still not being taken away from the sound generated from the band,” he says.

Taken as a whole, and in sequence, Rodriguez says that Grateful Dead live tapes are also a kind of history of the evolution of recording technology. He points specifically to early ’70s FOB (“front of board”) tapes as “amazing feats of strength” by those who made them.

“They made quality recordings with limited technology,” he says.

By the Dead’s later years, there was a “taper’s section” at concerts. Rodriguez explains that the designated area arose not so much to accommodate tapers, but to move them away from other concertgoers who were there simply to enjoy the experience. “The tapers’ section steered the annoyance that was the tapers into their own area so [the Dead’s crew] didn’t have to worry about them anymore,” Rodriguez says.

Even a hardcore Grateful Dead tape collector like Rodriguez has his limits. Collectors of Pink Floyd concert recordings, for example, obsess over the provenance of the tapes (or, these days, lossless digital files). There’s a seemingly never-ending quest to source the lowest-generation copy of any given recording. The argument is that until the advent of digital audio, each successive analog copy added a layer of hiss, and removed a degree of sonic quality. The nth generation copy one might have of the January 20, 1972 premiere of Eclipse: A Piece for Assorted Lunatics (which would soon be re-titled The Dark Side of the Moon) likely boasts significantly compromised fidelity compared to the original tape.

But Rodriguez draws the line at such obsessions. “I understand that to participate in that particular bit of nitpicking would drive me absolutely insane,” he says, sidestepping the unasked question about the sanity of collecting thousands of Grateful Dead tapes in the first place.

Many bands have engendered a level of fandom that extends to tape collecting. The Beatles, Pink Floyd and many others have extensive “unofficial” catalogs filled with non- or semi-sanctioned audio. But the Grateful Dead taping aesthetic is a world apart. Rodriguez attempts to explain what he thinks makes it different. “You have such fervent energy about trying to make the best recording possible given the circumstances,” he says.

And the Dead’s laissez-faire attitude about the whole taping phenomenon set the group in sharp contrast with an artist like King Crimson’s Robert Fripp, a vigorous opponent of audience recording. With the Dead, Rodriguez says admiringly, “It was permissible [for tapers] to experiment within the concert setting.” And the result is the massive, often high-quality archive that exists today.

The tape collecting community that grew up around the band is arguably a tangible example of the Grateful Dead’s fundamental aesthetic. “One goal of this particular band was to change culture, for people to relate to each other in idealistic or ‘utopic’ fashion,” he says. The tape-trading tradition had its start among people who could afford to buy mobile recording gear. But immersed as it was in the Dead’s milieu, the practice soon became a “free distribution thing,” Rodriguez says. And that fit well into the group’s egalitarian ideals.

Rodriguez doesn’t think that we’ll ever see another audience recording-and-collecting scene like the one that exists around the Grateful Dead. “I think it stands as a phenomenon of that block of time, from 1965 to 1995,” he says. “I don’t have any expectations of that form of energy existing again.”

There may never be another audience recording-and-collecting scene as dedicated as tapers were during those three decades. Still, it continued after Garcia’s passing, as the other Grateful Dead bandmembers have continued touring in various iterations. Since 2015, Dead & Company—featuring former Dead members Weir, Hart and Kreutzmann, with John Mayer, Oteil Burbridge and Jeff Chimenti—has filled hundreds of arenas for their live shows. A photo of the taping section at Dead & Company’s recent Wrigley Park concert reveals that same devoted fanbase.

Just a few days ago, the group announced that their 2023 summer tour would be their last. But even if there are no further incarnations of the band that started it all, the Grateful Dead’s tape-sharing community will likely keep the legacy of its performances alive forever.

‘After All is Said and Done’ is available at local bookstores.

As a mixed race kid growing up in an all white school, I was always on the fringe of life looking in. It wasn’t till I went to college and met my first Dead Hears that I discovered the idea of documenting my musical experiences with a tape recorder. My first Dead Show was Buffalo 11/9/79 & immediately fell in love with the Band & their Fan Base. I began collecting tapes & quickly realized I wanted to get in on the action. I bought my first deck a behemoth Marantz Superscope 330D 3 head deck that was 25lbs and took 8 D cells to run.

The first show I was able to sneak it into was a JGB show in Hartford CT 7/24/80. I am still amazed at how many shows I was able to get it into. I quickly realized I had to get a much smaller one if I wanted to continue to get quality boots & picked up a Sony WM-D6 while on a family trip to Hong Kong. It was then I started to record every concert I attended & have lots of non-Dead shows. Being a Taper gave me a chance to actually be accepted by the people who I met along the way for the first time in my life! Eventually as the Dead were winding down in the early 90s I had begun to find local musicians who allowed & appreciated me documenting their performances & gave me access to shows I wouldn’t have been aware of. It helped me find a way to connect with people when I had to move & I have more local musician recordings than Dead Shows or big name acts. Most of which I have uploaded to the Live Music Archives and The Videos I shot onto YouTube.

Would have preferred an author who had actually attended GD Shows and experienced the taper’s section first hand. This book seems bunk and void of real substance. The author of this review’s writing style also stinks. Time waister.