‘The land shouldn’t be for sale. It doesn’t belong to us; it belongs to the creator.’ —Patrick Yana-Hea Orozco

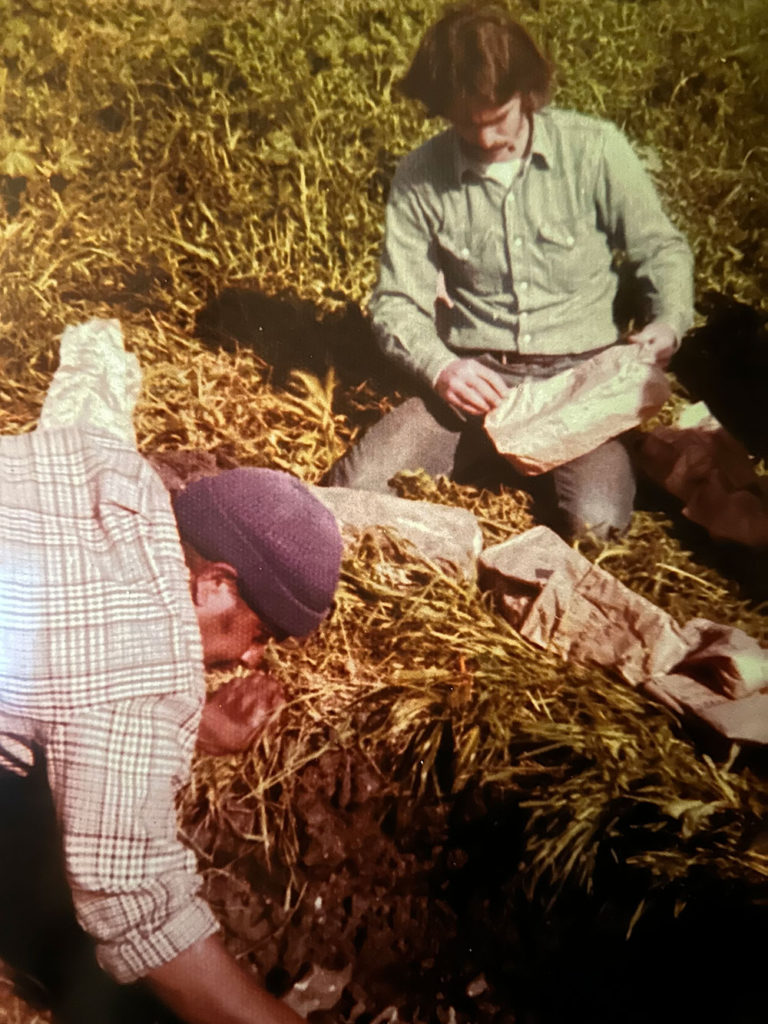

In February 1975, construction work near Watsonville desecrated an and bones and artifacts were removed by archeologists from UC Santa Cruz and Cabrillo College. When initial efforts by local Native families failed to protect the sacred site, the cemetery was occupied by a group of armed local Native families, activists and members of the American Indian Movement.

Patrick Yana-Hea Orozco, now 87, played a critical role in the direct action at “Wounded Lee” and will be honored at two events celebrating the 50th anniversary of this local Indigenous resistance at Cabrillo College on Oct. 14 and UCSC on Nov. 5.

Martin Rizzo-Martinez, an assistant professor in the Film and Digital Media Department at UCSC and author of We Are Not Animals: Indigenous Politics of Survival, Rebellion, and Reconstruction in Nineteenth Century California, is collecting oral histories for a new book on Wounded Lee and other 1970s grassroots Indigenous activism to protect graves and sacred sites.

Rizzo-Martinez says, “I began working with Patrick Orozco in 2020, helping to document Wounded Lee and other resistance in the Indigenous community here in the ’70s and ’80s. What Patrick and his family did was so important. It came at a time when there were no protections of native burial sites. In the 1970s archeologists were often going hand in hand with looters, and people would look for burial sites to loot them.”

He explains, “In 1975 a development project in Watsonville on Lee Road hit a burial site. Patrick and his grandparents had known about this burial site and would take care of it for many years, so when this happened they mobilized to occupy and protect the site, to prevent any further desecration. They were joined by American Indian Movement (AIM) members from the San Jose office and members of the Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association who had been mobilizing in similar ways up in Humboldt County. People came from all over; native people and allies.

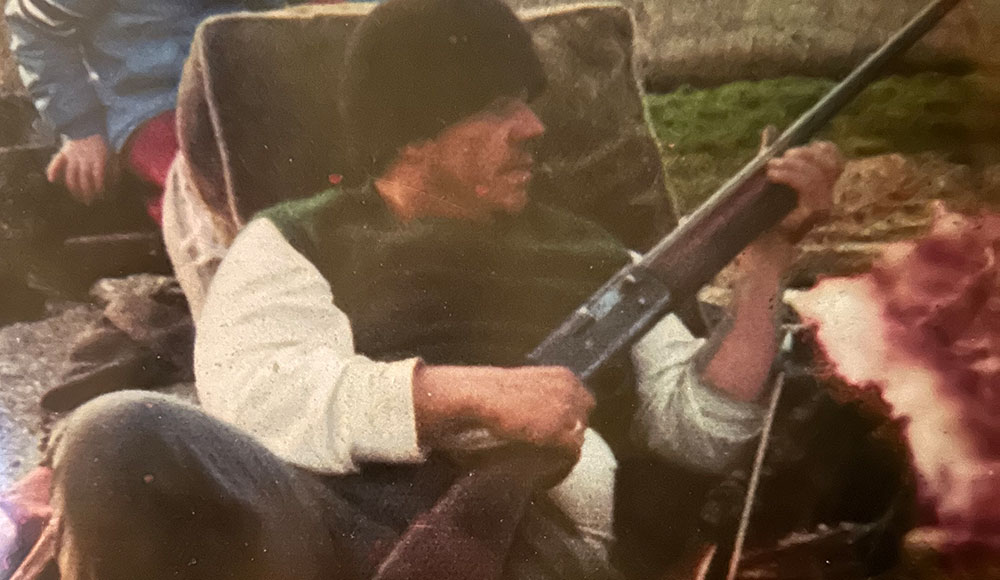

“At this point, County Sheriff Al Noren had just mobilized a SWAT force in Watsonville, and they were brought in,” Rizzo-Martinez continues. “This was March 1975 and it was a very tense month, with an armed presence ready to protect the sites and a SWAT force with grenade launchers and sharpshooters. There was a lot of uncertainty about which way this would go. Fortunately, there was no bloodshed. They were able to negotiate and find a solution.”

Patrick Yana-Hea Orozco provides a compelling firsthand narrative of these events, starting years before Wounded Lee.

“I first learned about the Lee Road burial site from my grandmother, when I was a kid,” Orozco recalls. “She was born in an old shack. Every two months they’d come into town for provisions in an old buckboard pulled by a horse and they’d come to the dirt road that connected to Lee Road. She told me, ‘Your grandpa would come back from town and stop in a certain place and you could hear him singing chants.’ But she never did explain exactly where the burial site was at.”

Orozco continues, “Then one day in 1975, I felt an unease, like when you go into an old house and you feel the people who were living there way before. And I heard some kind of humming or crying. I said, ‘What the heck is that? It must be the wind.’ After that, I opened the newspaper and saw that a burial site was discovered. I thought, ‘I bet I know where it’s at: Lee Road.’ So, I went over there. I picked up my uncle Frank, who was a garbage worker.

“We went to the burial site and found archeologists there,” he recollects. “They had about five graves uncovered and we raised hell. I says, ‘You guys should leave the graves alone.’ They started laughing at us. They said, ‘There’s no more Ohlone.’ That’s the first time I ever heard that word—Ohlone! The Indian people before us used to call ourselves either California Mission Indians or Costanoans, like ‘people of the coast.’ But I said, ‘I like that name, Ohlone.’’’

Orozco recalls, “We went through all the legalities and contacted the property owner, Aaron Berman, and met with his attorneys. They told us, ‘What if we give you another place to rebury your people?’ This was out of the question! But I wanted to be curious and he showed me on the map what he was offering us and I said, ‘Well, that’s underwater! That’s the slough!’ We realized these people have no intention to protect that cemetery.”

AMERICAN INDIAN MOVEMENT

“So, we decided to occupy the site. We met at the place called Coalition in Watsonville, and George Martin from the San Jose office of AIM stood on a box, and so did I,” Orozco recalls. They asked people to raise their hands if they wanted to participate.

“We also explained we might not come out of there alive,” he says.

Then only in his 30s, the possibility of dying didn’t occur to Orozco at the time. “I said, ‘Something’s got to be done, it’s got to stop now.’ So other people raised their hands to join us. That same night I loaded up my military Jeep with all my rifles, BB guns and bone arrows—everything I had,” Orozco remembers. “I went to the burial site and my brother and cousin were already there. Prior to that my aunt Irene (Avalos) called the Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association, whose head man was Victor Cutnose, and they met with us and decided to have us branch off of the organization. So we went to the county and did that, and then we decided just to go in. Vietnam Veterans Against the War showed up to serve as human shields. Chris Matthews and his brother were there. Chris became a great friend of mine,” Orozco says of Matthews, a former county supervisor and proprietor of Santa Cruz’s famed Poet and Patriot bar.

GRENADE LAUNCHERS AND SHARP SHOOTERS

“The Santa Cruz Sheriff heard about us occupying the site and surrounded us.” Orozco continues. “I remember seeing the property that belonged to Patrick Fitz; a mushroom company. They had haystacks piled up and I could see the military setting up grenade launchers. Everyone knew we wouldn’t have a chance. We only had .22 rifles and shotguns. But we wanted to set an example that we were willing to die for what we believe in: the protection of the place where our people were laid to rest. We were surrounded there by police, and Victor Cutnose came down and met with Gary Patton and Ken Boyd and all these county officials.

“Uncle Frank told me he was bringing in a guy that he met in Prunedale and I thought, ‘Something’s wrong here.’ So this guy comes into our dugout in the nighttime, and he was dressed in a suit. I thought, ‘This guy is an undercover man,’ and I told him right there before he even opened his mouth, ‘You’re undercover!’ Soon as I said that, he jumped up and ran out! He was an undercover cop and he wanted to see how heavily armed we were.”

I AM AN INDIAN, BUT WHO AM I?

“My aunt Irene was able to convince the landlord to sell the property to us for $17,500 to avoid bloodshed. So we dropped our arms and walked out. At that time, the thought came to me: ‘I am an Indian, but who am I?’ I wondered, ‘What has happened to our way of life? What happened to our traditional culture, our dances, songs, language?’” Orozco recollects.

“I started doing research on how our people lived. My grandma told me all about our family; she sang to me. When Wounded Lee happened she told us to do things in a peaceful way. “But if it doesn’t work, do what you have to do,” she said. I wrote a book called We Are All Related about what happened on Lee Road and the songs that were shared with me by my grandma.

“Then in 1978 the law was passed called the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. I said, ‘I got them by the horns. The cemetery is our religion.’ So I had an archeologist go in there, because I wanted to find out where the bottoms of the site was. I went to Aaron Berman and I told him I would help him get his warehouse built, as long as he gave us a cemetery and fifty-foot buffer. So he says, ‘You got it.’ He agreed, right there,” Orozco remembers.

“Governor Brown in 1976 decided to put together the Native American Heritage Commission in Sacramento, and me and my cousin were the first ones to sign up. In fact, we’re the ones that started the monitoring system with the state of California. Before that, they used to just go in and start digging. After, they had to contact the Heritage Committee and have us monitor construction,” Orozco explains.

And to this day, he is still on the Heritage Commission list.

I’M STILL AN OLD WARRIOR

“As far as the cemetery now, we mow it, keep it clean, and we’re planting native plants around the boundaries of the cemetery where we have our spiritual and ceremonial gatherings,” Orozco says. “I also work with Santa Cruz Land Trust and go into schools to tell kids the history behind our people, how we lived, what we ate, how we made our arrowheads and baskets and everything I learned from my grandma, like the use of plants and herbs.

“Fifty years went by fast!” Orozco says, laughing. “I’m 87 years old now and I’m still an old warrior, still doing what I have to do, recommending monitoring if it’s necessary. I managed to preserve nine burial sites already. The largest one was over in San Francisco. That took us a year. The Holiday Inn site took about a year [San Jose, 1977]. Thirty-nine graves were removed and later returned. But there’s no such thing as a reburial ceremony. The only artifact that was not returned was an abalone pendant called kuksu.”

Orozco adds, “This happened only two years after the AIM standoff at Wounded Knee in South Dakota, so the police were worried there would be a war. They probably were thinking, ‘You don’t mess around with the American Indian Movement.’ We tried to avoid militant ways. But we were backed up in the corner and we had to do it. And the developer ended up donating the cemetery back to us, with a buffer zone.”

Jesse Malley, a student who works at the Cabrillo College Multicultural Student Center, helped organize the Oct 14 event at Cabrillo College. “It’s incredibly important to create opportunities for people to connect with local Native people and know the history of the land we’re on,” Malley says. “Patrick has a lot to offer for gaining perspective on the history of the vital, vibrant movements here.”

Angel Riotutar, who has been director of the American Indian Resource Center at UCSC for three years, looks forward to the Nov. 5 event at UCSC. “The Santa Cruz Indian Council was started by my family, and what has been really important for me is to advocate for our native relatives and making sure there’s accurate history being told. My grandmother had nine children and half of them were at Wounded Lee, protecting the land. So, we’re bringing this commemorative anniversary to Santa Cruz, with Patrick Orozco as the focus, as a guide and leader in pursuing justice.”

Patrick Yana-Hea Orozco will be at Cabrillo College on Oct. 14, 9:40–11am, and at UCSC on Nov. 5 at noon at the Cowell Haybarn; an RSVP is requested due to limited seating. For details, contact Je******@******lo.edu.

Listen to this interview with Patrick Yana-Hea Orozco on Thursday at noon on Transformation Highway with John Malkin on KZSC Santa Cruz 88.1 FM / kzsc.org.

Bumper stickers I made long ago:

REDWOOD FOREST:

LOVE IT OR

LEAVE IT OHLONE

Yes, the day Native Americans took over Lee Road in Watsonville. I was one of the ones to sneak in to back up my word with action. I at 19 felt, we had done enough damage to Natives of this land, stole the continent from under them, genocided them, and then digging up their sacred ancestors. Words without action equal nothing.