In early 2020, the Watsonville City Council approved a plan for how Santa Cruz County’s southernmost city would improve its parks and recreation offerings. The 2020 Parks and Recreation Strategic Plan identified the potential of the city’s parks, but it also highlighted the decades-long deficiencies that have plagued the city’s parks department. It showed that not only was the city’s available park space per 1,000 residents gravely behind the national standard, but also that the park space available was largely in disrepair, with the city facing some $18 million in deferred maintenance because of low revenues.

And yet, just a year-and-a-half later, Watsonville’s parks department is in arguably the strongest position it has been in recent memory. Case in point: a roughly $22 million infusion of local, state and federal funding for a complete renovation of Ramsay Park, its largest recreation outlet. The wholesale facelift that will happen over the next five years includes the construction of an inclusive park, a completely reimagined Nature Center, and the long-awaited modernization of the two fields at Sotomayor Soccer Field.

For some, the massive investment of taxpayer dollars—at least a third of which is federal funding from President Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan Act—might seem like a misstep from local elected leaders. But Raquel Pulido, who helped lead the charge in convincing the Watsonville City Council to make the investment, knows exactly how much a renovation of Ramsay will mean to Watsonville’s soccer-crazed community, which has long struggled to find fields to play on.

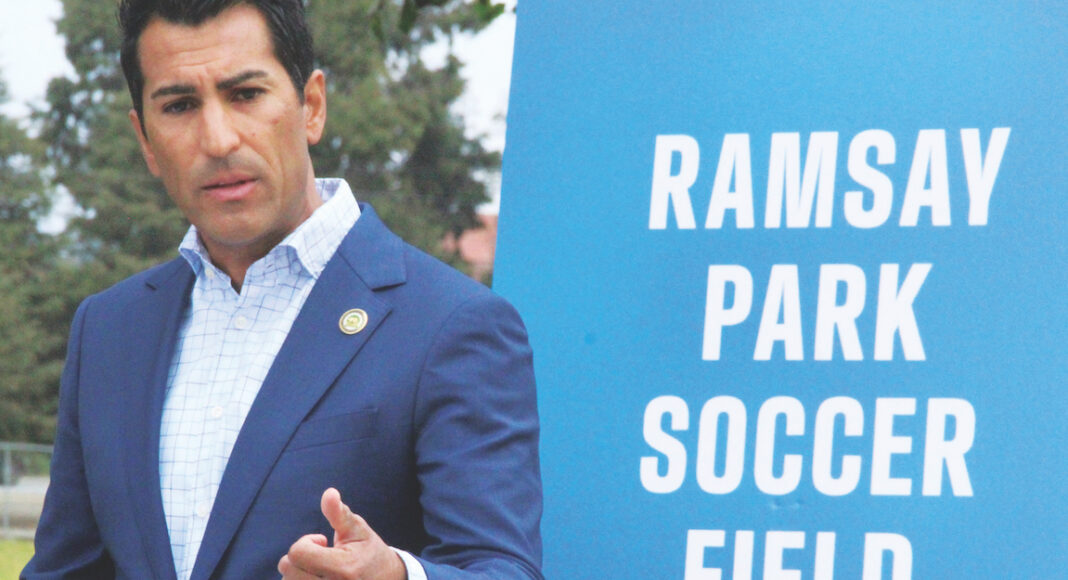

“It’s a dream come true,” said Pulido, as politicians, community leaders and city employees took photos after a Sept. 17 press conference recognizing the renovation’s milestone. “We had the plan, but obviously didn’t have the funds. Now that it all came together, I’m really excited for what it’s going to do for our community.”

Soccer City

There are few things that are more synonymous with Watsonville than soccer, and yet the limited locations to play the beautiful game within city limits paints a different portrait of the community’s connection to it.

As it stands today, Ramsay Park is one of the few spots under the city’s 143 acres of park space that offers a full-sized soccer pitch. But the two fields there are often unplayable because of excessive usage, flooding from poor drainage and a lack of lighting as fall and winter set in and sunlight dwindles. As a team manager for her son’s competitive squad, Pulido knows firsthand how difficult it is to find a place for a team to practice, let alone play. Sometimes, Pulido says, that means moving practice to hardwood basketball courts for games that will take place on grass fields.

This predicament, says Pajaro Valley Youth Soccer Club (PVYSC) coach Gladys Mondragon, is nothing new. The Watsonville High School and Cabrillo College alumna remembers having to practice on the corner of a softball field when she was young, and her youth team often played on the road because there were no fields available to host games. Even now, as the head coach of the Watsonville High girls’ team and the Cabrillo College women’s team, Mondragon says space and time to practice remains tight around Watsonville because of the high demand of youth, school and adult teams that operate in the area.

Despite all of this, Watsonville’s youth soccer teams have consistently found success. Pulido boasts that her son’s team has placed first and second at state tournaments. PVYSC teams, also known as Pajaro Valley United, have won several championships and traveled around the country to play in high-level tournaments. And the Watsonville High boys’ team is often tops in the state and among the best in the nation some years.

That success, Mondragon says, speaks to the love for the game that permeates through many facets of the community. It’s commonplace to see people playing a pick-up game of soccer on the street with random items—shoes, traffic cones, sweaters or plants—placed as goalposts. So, too, is it to see a group playing deep into the night with car headlights dimly illuminating a field, or using an empty tennis court to play futsal—a compact version of soccer typically played indoors.

“I think it shows the commitment of the coaches, the commitment of the parents and the commitment of the athletes, regardless of the resources that we have, to manage to figure things out and continue to do what we love to do most,” Mondragon says. “[They find] an open space; if it’s a futsal [court] or a corner on a grass field, they manage to continue playing. Sometimes street soccer makes good players, too.”

Soccer, Mondragon says, is many times a common language that brings people together. And that is important for a city that has prided itself on welcoming immigrants. For many people that have decided to move here and call the U.S. home, soccer has been the connective tissue that has given them a chance to find a community.

“It’s not just a sport. It provides so many different things,” she says. “The connection you have with your teammates, your coaches and the connection that it creates with the community. The feeling of belonging to something, you know?”

Dream Big

On top of the Ramsay renovations, the city recently partnered with the Pajaro Valley Unified School District (PVUSD) on a joint-use agreement that will allow the municipality to use the fields at three schools when class is not in session. The hope, officials from both institutions have said, is that the agreement will lead to a long-range plan of how PVUSD can open up more of its fields for public use. The city is also weighing whether it will implement a sales tax that would solely benefit its parks department, and working to update the fees it charges developers that feed back into its parks.

City officials are not alone in trying to solve the community’s field shortage dilemma.

The Pajaro Valley Sports Foundation (PVSF), a committee of community leaders gathered for the sole purpose of creating more soccer fields in Watsonville, is a couple of months away from unveiling a renovated soccer mini-complex at Freedom Elementary School. The project, says local attorney and Watsonville Rotarian Tom House, is the result of years of grassroots organizing and fundraising supported by numerous donations big and small, from people volunteering to dig trenches at the field on weekends to farmers and businesses in Watsonville giving monetary gifts.

“This was not a hard sale to raise the funds. It was just the matter of asking enough people, and very few said no,” House says. “I think [they] understand this is good for the community.”

House says the calls for additional soccer fields—and the benefits they would provide for Watsonville’s young people—were hard to ignore. A few years ago, legendary Watsonville High soccer coach Roland Hedgpeth and revolutionary community leader and probation officer Gina Castaneda spoke to Watsonville Rotary within two months of one another. At the end of their respective presentations, Rotary asked the soccer community giants what they could do to support their mission.

“They both said the same thing: ‘We don’t have enough soccer fields for the kids that want to play in the area,’” House says.

So the Rotarians rolled up their sleeves and got to work, creating PVSF and drafting a plan of how to solve the issue. They first dreamt big, House says, trying to find vacant land on the outskirts of the city that could be converted into a sports complex similar to sprawling sports centers in Morgan Hill and Sunnyvale. But restrictions on land use, specifically on the conversion of agricultural land, made that a difficult proposition.

PVSF pivoted to another, smaller option: refurbishing an existing field within city limits to show what they were capable of. Working with PVUSD, Pajaro Valley United and the Community Health Trust of Pajaro Valley, PVSF got the OK to move forward with the project. They would turn the gopher-hole-riddled field at the school in the heart of the north side of the city into a sparkling three-field soccer complex, and in return, Pajaro Valley United would have a place where more than 200 youth soccer players can practice and play games.

Initial estimates put the project around $270,000. House says they raised roughly $350,000.

House says bringing a larger sports complex is still PVSF’s ultimate goal. At the moment, there is no clear path forward for the project, but he believes the benefits of a sports complex will make the project too good for the community to say no.

“I think Watsonville can use lots and lots more parks with fields and activities for kids to be engaged in constructive stuff and away from doing bad stuff,” House says.

True Equity

Mondragon says the fields at Freedom Elementary will serve as a home base for Pajaro Valley United, and allow the program to continue to grow at a key inflection point in which more girls locally have become interested in playing competitive soccer.

Since taking the helm at Watsonville High shortly after graduating in 2002, Mondragon has helped the local landscape of the girls’ game evolve. When she played youth soccer, there were no local programs that gave Watsonville’s girls an opportunity to move up the competitive ranks. Many of the girls who wanted to keep playing competitively had to move to programs that played and practiced in Santa Cruz—a dealbreaker for those who had no transportation.

Through PV United, Mondragon pushed in 2007 for the start of more competitive teams for Watsonville’s girls.

“My thing was to provide for the community and have more girls be able to travel and have the exposure that I had when I was young,” she says. “And it’s happening now. Some of them are playing college, some of them are transferring out.”

Back then, that wasn’t an easy sell, Mondragon says. After all, she wasn’t only trying to convince young girls that through playing soccer they could get a portion—if not all—of their college expenses paid for; she was also tasked with breaking Latinx cultural barriers that still exist in some families today.

Local artist Jessica Carrasco knows those barriers all too well. When she played youth soccer in the early 2000s, the girls’ competitive scene in Watsonville was still in its fledgling stage, so she decided to play on boys’ teams. She remembers hearing “Futbol es para hombres” (soccer is for men).

“I feel like a lot of us who played who are [in] our 30s and 20s right now, we grew up with that mentality, but at the same time we loved it so much that we didn’t care,” she says. “You could label us as tomboys, whatever you wanted to label us. We loved playing.”

Carrasco says that the recent explosion of girls’ competitive teams in Watsonville has given her hope for the future, but adds that more needs to be done to make sure the game continues to grow. The former Watsonville Parks and Recreation Commissioner says that as the city adds soccer fields she hopes it will also start up a women’s soccer league as well.

“This is awesome that you’re advocating for these fields, but how equitable are we going to be?” she asks. “Are these fields going to be again for the men and youth, or are you going to open them up for women?”

To donate to PVSF’s renovation of the Freedom Elementary School field or for information about their cause, visit their Facebook page.