In recent years, the story of the three Hawaiian princes—David Kawananakoa, Edward Keliiahonui and Jonah Kuhio Kalaniana’ole—transporting the Hawaiian sport of surfing to Santa Cruz in the 1880s has been woven into the fabric of local lore.

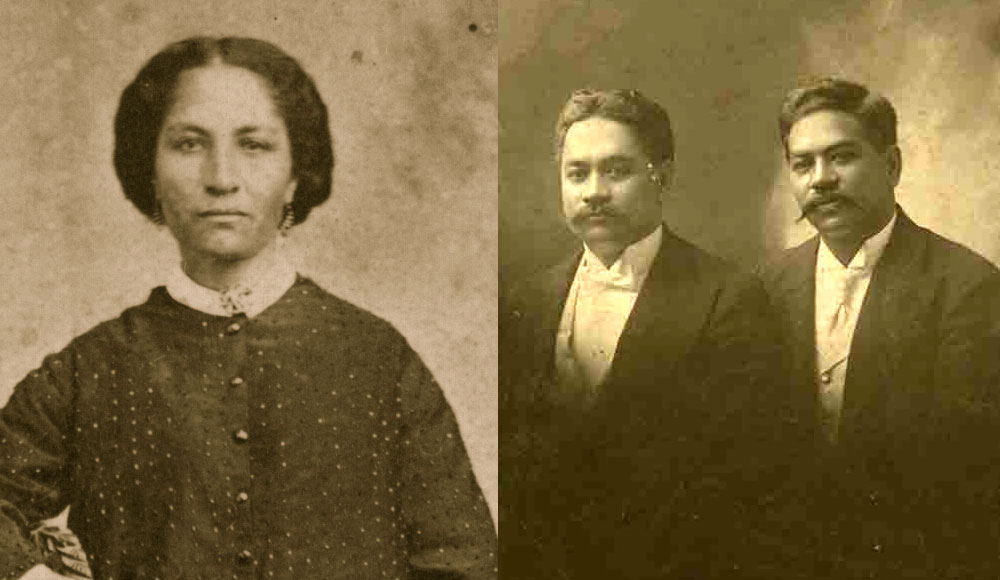

Moreover, the role that Antoinette Swan, the Hawaiian-born matriarch of a prominent business family in Santa Cruz, played in chaperoning the princes on their local sojourn has also been duly celebrated, including at the popular exhibit, Heʻe Nalu Santa Cruz, currently staged at the Museum of Art and History through Jan. 4 of next year.

The focus of the narrative, of course, has been on the princes’ wave-riding exploits at the mouth of the San Lorenzo River on July 19, 1885, perhaps deservedly so. That attention, however, has narrowed the historic perception of what was a much broader, more profound and complex relationship to the greater Santa Cruz community. Further research of the archival record reveals that the three princes were much more broadly involved in the day-to-day dynamics of their host city than their celebrated one-day activities at the mouth of the San Lorenzo River might suggest.

While it’s been well chronicled that the eldest of the princes, David, arrived in Northern California to study at St. Matthew’s Hall, a military school for boys located in San Mateo, as early as 1884, local newspapers began identifying their activities here frequently following their arrival.

On the weekend before their celebrated surfing exhibition, for instance, the Santa Cruz Sentinel noted that “the Olympic Rink [downtown] was honored by the presence of the Hawaiian princes, Friday evening, who received their first lesson in skating. They fell down about as many times as ordinary individuals.” A pair of skates, the newspaper opined, “has no respect for rank. They level all persons who can’t skate.”

The day after their wave-riding exploits, the Sentinel reported that “one of the Hawaiian princes jumped off the Railroad bridge” and “struck the water [with] a ‘dull thud.’”

The following winter, in January of 1886, it was noted that “the Hawaiian princes will return to their college at San Mateo today, after spending their [Christmas] vacation in this city. They had made Santa Cruz their home away from home.

An item in the San Francisco Call in July of 1886 noted in an “item from Santa Cruz” that “a number of Honolulu people visiting here, and a luau was given in their honor, on Tuesday evening… Three Hawaiian princes were present, and the menu included the native dishes, poi and Komenolomi [likely made from salted salmon, tomatoes, and onions].”

The following summer, the princes were back in Santa Cruz again, during which time they participated in a “reception” held aboard the Claus Spreckels’ lavish family yacht, the Lurline. “The Hawaiian Princes played their guitars and mondolins,” the Sentinel reported, “playing the music of their native land. The ‘hula hula’, the national dance of Hawaii, was danced by two of the jolly yachtsmen, much to the amusement of the spectators.”

Their performance at St. Matthews was also reported by the Honolulu Advertiser of June 11, 1887, in great detail. David received scores of 100 for punctuality, military conduct and scripture, 95 in deportment, 87 in music, 85 in French, while dropping to 47 in geometry. Jonah received a 100 in writing, 99 in punctuality and military conduct, while below 80 solely in elocution, in which he received a 77. Edward also received outstanding grades, with perfect scores in punctuality, deportment, military conduct and writing, while dipping to an 83 in the violin, and a 73 in algebra.

Then came tragic news. On October 6, 1887, the Sentinel reported that: “His Highness Prince Edward Keliiahonui, who has spent a number of summers in Santa Cruz, breathed his last at Iolani Palace, Honolulu, on September 24th. For some time he has been prosecuting his studies at St. Matthews Hall, and was taken ill. The resident physician at St. Matthews thought it best for the young Prince to be sent to his native land…Arriving at the Palace, medical aid was summoned, and it was that he was suffering from an attack of typhoid fever, with little hope of recovery.” He died shortly thereafter. He was only 18.

As late as November of 1889, the two surviving princes were still visiting Santa Cruz, according to the Sentinel, “where they are the guests of Mrs. L. Swan.” As it turned out, the royals were on their way to Britain, where they were to further their education abroad once again. It’s possible the pair had taken their sidetrip to Santa Cruz to retrieve the redwood surfboards that they had crafted in Santa Cruz four years earlier, as it has been recently discovered that they surfed in Britain.

In a letter written by Jonah while in England, he noted that the brothers had traveled to the British coastal resort of Bridlington as reward for good work in their studies. “We enjoy the seaside very much and are out swimming every day,” he declared. “The weather has been very windy these few days and we like it very much for we like the sea to be rough so that we are able to have surf riding. We enjoy surf riding very much and surprise the people to see us riding on the surf.”

Upon their return to Honolulu, however, the princes faced an imposing imperial threat. In January of 1893, a group of American and European businessman, aided by the U.S. military, overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy.

Two years later, then 24-year-old Jonah, a fierce advocate for Hawaiian independence, fought in a rebellion against the U.S.-supported republic and was sentenced to a year in prison. While Kuhio was incarcerated across the Pacific, the weekly edition of the Santa Cruz Surf in July 1896 made the fascinating observation that “the boys who go in swimming at Seabright Beach use surfboards to ride the breakers, like the Hawaiians.”

Their legacy—in Santa Cruz and along the Pacific Coast—had taken root. But by then, the two princes had put Santa Cruz behind them. They had bigger fish to fry.

Jonah left Hawaii immediately upon his release from prison and traveled the world. In 1902, he returned from exile to participate in Hawaiian politics. While his brother David headed up the state’s Democratic Party (and was a delegate to the 1900 Democratic National Convention), Jonah joined the Republican Party (as a supporter of Teddy Roosevelt) and was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1903 as a “delegate” from the Territory of Hawaii, a position in which he served for nearly 20 years.

Back in Santa Cruz, a final coda to the princes’ story appeared in the Santa Cruz Surf on October 2, 1905, in the form of an obituary for “Mrs. Antoinette Don Paul Marie Swan,” who had died the day before at her family home on Cathcart Street. The obituary noted that Swan “was courtly in manner, and had a charm in her dealing with people that won many friends. She was a kind neighbor and a devoted mother, loved by her children.”

She was clearly a well-liked and widely respected member of the community.

Local surf historians Kim Stoner and Don Iglesias will give a guided tour of the Heʻe Nalu Santa Cruz exhibit at 6pm on Friday, Nov. 7 at the Museum of Art and History, 705 Front St., Santa Cruz. Free.

Awesome

Gone, gone, gone beyond.

Gunboat Steve