TITLE SCREEN: This article is a puzzle word game about an amazing storyteller and a singular Santa Cruz artist, Edmund McMillen, an auteur who makes indie video games where the cybernated characters are reflections of his own very personal journey.

Think the Quentin Tarantino of small-budget video games, without the foot fetish and gregarious personality.

In person, the laughing, Melvin’s lovin’, tatted McMillen and his wife, Danielle (who is running around in pajamas), are at the end, or beginning (life and video games are tricky about that) of a six-year journey leading to the release of McMillen’s newest venture.

Another game, in an oeuvre that is built out of his own genetic structure and unique personal expressions that he shares with his wife, children and cats (foreshadowing).

LORE

By 2010, video games were an insanely lucrative market. Call of Duty: Black Ops sold over 12 million copies. For perspective in the same year, the biggest selling music album was Eminem’s Recovery which sold only a third of that, worldwide. Between games and hardware, in 2010, the electronic game industry took in almost $19 billion. Franchises like the Super Mario Bros and Madden NFL were swimming in mushrooms, gold coins, touchdowns and field goals.

Meanwhile, squirreled away in his bedroom, in Santa Cruz, working on a game that was to be called Super Meat Boy, was our hero and industry influencer wizard, Edmund McMillen. His games were drastically simple compared to Halo and Red Dead Redemption, but it was the beginning of a series of games that would not only change McMillen’s life and two documentary filmmakers’ lives, but would also touch the hearts of millions of gamers. Millions.

Through it all, McMillen is, in two words, humble and funny. But more so, McMillen and the worlds he creates are honest and self-revealing to a degree that is rarely seen these days. Even his Wikipedia page has more emotional content (gleaned from his numerous interviews) than what occurs in most therapy sessions

ZONE

Growing up with his mother and stepfather, who had an on-again, off-again relationship, McMillen was raised most of the time by his grandmother in Watsonville.

“She wasn’t an artist. I mean, she supported me throughout. But nobody in my family was really an artist. My stepdad was somewhat of an artist and showed me how to shade and stuff like that. But my main interest in drawing just came from my obsession to draw Ninja Turtles in the mid ‘80s. I really was obsessed with drawing Ninja Turtles. I think a few people commented that I was good at it, and since I wasn’t good at anything else, I realized that maybe if I focus on drawing, people would like me. It was that dopamine hit from being complimented on something for the first time,” the young artist relates from his home in the hills of Santa Cruz County.

Like some youth, unable to provide effective change in a tumultuous family, McMillen dove into the solitary lifestyle of drawing and self-publishing comic books– a world where he controlled actions and outcomes.

His artistic inspiration arrived in a symbiotic, fortuitous encounter, much like how his characters in his games advance; circumstance is what drove the mission.

‘I found an R. Crumb comic inside a Mad Magazine in 5th grade that somebody had brought in and donated to the classroom. And, I took it,” McMillen laughs. By hook or by crook, the budding entrepreneur sold his ‘’adult” comic books locally at Streetlight Records, Borders and Comicopolis.

Back home things were not easy, and McMillen’s grandmother provided respite from emotional storms.

‘’She was super supportive. I mean, it was like a half-and-half situation. My mom would move in with my grandma in Watsonville whenever we were in transition around Santa Cruz. And I spent a great deal of time with her and eventually ended up living with her as a teenager. And even though she was a devout Catholic, she, for some reason, always supported whatever it was I was doing, even though it was not something she would be into,” McMillen says.

That’s when McMillen took the next step of making a video game, and eventually, the underlying context of the narrative would be his own life.

“Yeah. I made a game. I made a whole game about it,” he says off-handedly.

AUTEUR

McMillen, like a ton of kids growing up in Santa Cruz County in the 1980s, many had a Nintendo, or at least played Nintendo. By 1990, over a hundred million units were sold worldwide. Which is right around when McMillen got his. “I was like the last kid on my block. I got a Nintendo right when Super Nintendo was coming out. But it was still awesome, and everybody else on my block had Nintendos, and I’d go over and play their games and stuff, and I was super obsessed with Zelda and Mario 2 and Castlevania. I played a lot. It was never really like I considered it as a career until I was doing it.”

The young gamer thought he would either move full-time into publishing comics or animation. With no publisher picking up his comic books that included tutorials on what to do with dead babies (i.e. target practice, shark chum, or car boot), McMillen, through sheer frustration decided to take his comics online.

“I took some HTML Dreamweaver web design classes at Cabrillo and got what I needed. I failed those classes, but I still understood how to do it. I went home, made my websites, and started hosting my comics online.

“And in that transition, one of the web tools that you used in the late ’90s and early 2000s was a thing called Flash. And it was just like an interactive website, which had some scripting to it. And through that, I made interactive comics. And that turned into really basic video game stuff. I didn’t even consider myself making games though. I still felt like I was making animations that you clicked a button to get through. Point and click and drag,” says McMillen.

He had an early hit, heralding his ability to charm the world with a talented nose for developing trends, with Dead Baby Dress Up. The static blue dead babies of McMillen’s early comic books were now digitally able to be dressed up from a pile of wigs, hats and teeth. It’s a simple, super intuitive and fun game. But, blue dead babies?

If you dig a bit you’ll see that McMillen has some innate ability to suss out weird zeitgeist moments, as Dead Baby Dress Up, coincided with Roman Dirge’s comic book, Lenore, The Cute Little Dead Girl, as well as the beginning of the Walking Dead. Dead babies were in vogue! It was a hit.

Suddenly, magazines in the United Kingdom were talking about McMillen. This flash of underground credibility raised his real estate and brought a pairing together that was– as many encounters in McMillen’s life were and continue to be–fortuitous.

First, it was Newgrounds, which was a supportive online community of indie games, gamers and a place to host flash animation and eventually flash games. This was the toehold, but it was also a Santa Cruz company called Chronic Logic, who were committed to the principle that challenging fun games could be made without corporate funding.

“I found Chronic Logic back then, and they had done a game called Pontifex. It was a bridge-building physics simulation game. I had just lost my job as an animal control officer locally,” says McMillen.

PAUSE

“I liked being an animal control officer,” McMillen begins on a defining story that could have derailed his current life’s direction. “I lost the job when it went from SPCA to county. All of a sudden the county required employees to have high school diplomas, which some of my higher ups didn’t have.”

What had been a peaceful job scraping dead raccoons off the roads, now became a bizarre conspiracy.

“I found out that they were taking notes about every time I didn’t fill the gas tank up all the way when I dropped it off. Like I’m in Watsonville, getting a call for a blind pit bull that won’t get off somebody’s doorstep. And these people that are supposed to back me up, are not there for me. They’re not helping me. So I quit.

“Then they begged me to come back and said they were going to give me a raise. I went back and within two weeks, once they found somebody to replace me, they fired me. I had never felt so wronged in my life.”

RESUMING

After he was fired, McMillen was at a dire crossroads. Unable to figure out what to do to earn money and find value in his existence, he quadrupled down on choosing artist from life’s menu options. But, his portfolio was just a bunch of dead blue babies. Which is when he chose to walk into the office of Chronic Logic.

“They were literally two blocks from my house off of Mission,” says McMillen. “I told them I’d work for free, because I’m building a portfolio. They hired me within a couple months and I started working on games and I pitched this game called Gish.”

Gish is a lump of tacky tar who lives in peaceful co-existence with his non-tar, human girlfriend, Brea. Then one day, Brea goes missing.

This was the first time that McMillen had something online that wasn’t a freebie that consumers had to pay for. “With Gish, I finally realized that I’m a game designer making video games. l felt like I have something to offer in this medium that is more unique than comics,” McMillen quips.

That’s when McMillen took the next step of making a video game that would rock the indie gamer world, and the underlying context of the narrative would be his own life.

SURVIVOR

When you hear that somebody’s video game deeply impacted millions of people around the world, it sounds like hyperbole, but in McMillen’s case, it rings true.

The year Super Meat Boy hit Steam in 2010, the release was at the front lines of an indie game revolution. Braid (an indie puzzle-platform video game) came out in 2008 and caught everybody’s attention with its time rewinding mechanics. With Super Meat Boy just around the corner, about a skinless red cube, who tries to rescue his heavily bandaged girlfriend, fans were drooling for something new from McMillen.

So what does a broken child of divorce, living in a small, unknown town in Romania with parents who were addicts, and was now forced to be on meds to deal with his own trauma, have in common with an indie game designer in Santa Cruz, California? Enter Tudor.

“I was living on a university campus (in Romania) with a gamer friend of mine who introduced me to Super Meat Boy the day it launched. With its immersive, dystopian, dark-level design, challenging difficulty and our main character’s happy-go-lucky attitude it was becoming quite clear that Edmund had me in his clutches. We stayed up all night finishing the game, and for a couple of months we fought bare-fisted with anything that stood in our path to unlock everything the game had to offer,” says the new father from Romania.

Fast forward one year (2011) and McMillen released his newest revolutionary indie game, Binding of Isaac.

According to Tudor, it was “Darker, murkier and much more engaging on an emotional level than anything released before. A complex story about a crying child trying to escape his religious puritan mother, finding his way through the basement only to unfold a series of mysteries about his family.

“It clicked with me instantly. The target audience is wide – a beach of indie lovers – but I always thought this game connected on another level with those who are emotionally scarred. It is riddled with triggers that either provoke the player or offer a moment of deep introspection. To be quite fair, I feel like I’m almost indebted to Edmund, as his games can be used as tools for self-healing. For some, it can be a band-aid and for others it can be the medicine they were looking for all along.”

So when McMillen says, “Yeah. I made a game. I made a whole game about it,” that’s him being humble. Because the reality is his “games” have changed lives.

AVATARS

In 2009, based in Winnipeg, Canada, Lisanne Pajot and James Swirsky were interested in making a documentary about video games created by individuals or by small teams without large financial backing.

The dynamic duo began talking with a local developer, inquiring about who was worthwhile to interview in a world of outsiders. Who was working on a game they could document the process of?

They heard about Edmund McMillen and his developer partner at the time, Tommy Refenes. What struck them as interesting was that the game hadn’t been made yet, but McMillen was reluctantly highly visible in the underground, connecting and promoting, and trying to find a fanbase.

“They were really hustling,” says Pajot, who along with Swirsky are in Santa Cruz filming a yet unfocused project, perhaps, centering around McMillen’s world.

“And so we sort of tracked him down and then kind of followed him around GDC, which is the Game Developers Conference, but didn’t quite connect with him, not knowing that going to big public events is kind of like a hard thing for him. But then at the end of the conference, he said, ‘Why don’t you come to Santa Cruz and we can talk more?’

And so we did, and then spending time with him and his wife Danielle and Tommy, was just really inspirational.”

VISIONS

This is a tricky time for the gaming industry. The big corporations like Sony, Microsoft and Amazon are mowing down jobs. Sony Interactive Entertainment has been slashing employees and closing studios. With bigger name titles facing declining revenues, production costs rising and consumer spending on a downward spiral, the entire gaming industry is in the midst of a sea change that is sending tsunami-sized ripples outward. Not to mention the hotly debated incentives to utilize AI instead of humans for design and coding.

“A lot of games now, you know, I’m sure any gamer reading this knows that most games that are played are big subscription-style games like Fortnite or like Roblox or Minecraft,” Pajot begins.

“New titles, new individual titles coming out have a harder time getting eyeballs. And it is because there’s such a massive amount of games coming out, it’s really hard to get seen. And the special thing about Ed is he’s been developing an audience for 15 years. He’s been talking to gamers this entire time throughout his whole games because he himself is like a fan. He’s a super fan of many influences. And so he’s trying to serve this audience as he’s going.

“He is hustling right now to promote this next game (more foreshadowing). It doesn’t really matter, like in the scope of his life, whether this financially does well or not. But despite that, he is still hustling, as if he had something to lose to try to get his game out there, he worked on it for so long.

He has Tyler (Glaiel, his new creative partner). He has a team. He has that kind of pressure, but it’s an especially hard time right now to get indie games seen, and it’s a different time than it was back in 2010. when they put out Super Meat Boy. So it’s like the economy of games is in a different sort of flux period, and people are going bankrupt. Like, it’s a whole thing happening right now. So he’s putting out this game into this environment, and he’s working really hard at it. It’s not about building a huge big audience, but there’s no kind of guarantee on how this will play out,” Pajot explains.

BIG REVEAL

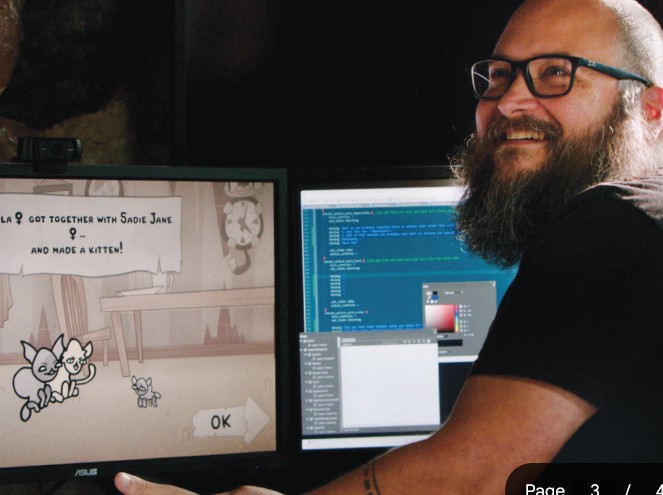

McMillen’s newest dream about to be made manifest is Mewgenics, which launches on February 10. According to McMillen, who is laboring away trying to get the credits for the game ironed out in the final moments, “It’s a cat breeding simulation. It’s like a cat hoarder game where you hoard cats in an abandoned house. You breed them. And then you take them on adventures in a kind of D&D style.

“Like putting them in different classes. They gain abilities and loadouts that are similar to those D&D classes, like a thief or whatever else. And then you play turn-based combat events and random events, or you do skill checks, and then you get loot and furniture for your house and defeat bosses and harvest food and save up money and then try to survive enough to come back to the house, so then you can breed those cats with previous cats or stray cats in hopes that you will retain the skills that they left with, or that they ended with, and then go on more adventures and then the game just continuously. It’s like the Binding of Isaac, it just keeps opening up and unfolding and does that for a long time,” McMillen reveals.

ENDGAME

Among game developers of that early era, Watsonville, and now Santa Cruz resident, Edmund McMillen is considered somewhat of a prophet. The award-winning 2012 documentary that Pajot and Swirsky released Indie Game: The Movie, which stars McMillen as one of three indie game developers, has a 93% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes. But there’s something new in the works, coinciding with the upcoming release of Mewgenics. “We started filming him in 2010 and have been off and on filming with him for 15 years. We’re working on something that is yet to be determined, but we have been lucky enough to spend time with him and his family. It’s really interesting to see him develop as an artist, coming from an upbringing that struggled with poverty, but also as a person. I think he’s very self-reflective. And every time you talk to him, you learn something about him, but then you learn something about yourself, which is the special thing about him. It’s his vulnerability and his honesty and the way he shares his story and seeing the things that he’s working through, and puts inside his games,” Pajot shares.

EASTER EGG

Why a game about cat hoarders you might ask? Is that actually something that McMillen has going on in his own life? Well, of course it is. “It was kind of a joke,” McMillen laughs.

“My wife had a rule for a while that if I was starting a new project that she would get a new cat. A movie spoiler of Indie Game is that the movie concludes with my wife getting her first hairless cat, which is what she wants through the whole movie.

And by the time I was working on Mewgenics, we had four. And they were all weird, exotic cats. Some stray cats that we’ve brought in over time, but a few hairless cats. I thought it would be funny to kind of make a game about that, like as a joke. About my wife being a cat hoarder, and the kind of moral weirdness of purchasing purebred cats that have abnormalities that people like.” And that is the origin story of McMillen’s latest excursion into sharing with the world his personal journey. A journey that is still unfolding.

Mewgenics will be available on Steam Feb 10 and can be linked directly with Mewgenics.com and will release on consoles later this year.

Loved this, DNA. The vulnerability really lands in this strange moment we’re in, and you make the game sound truly special. Proud of the local storytelling…