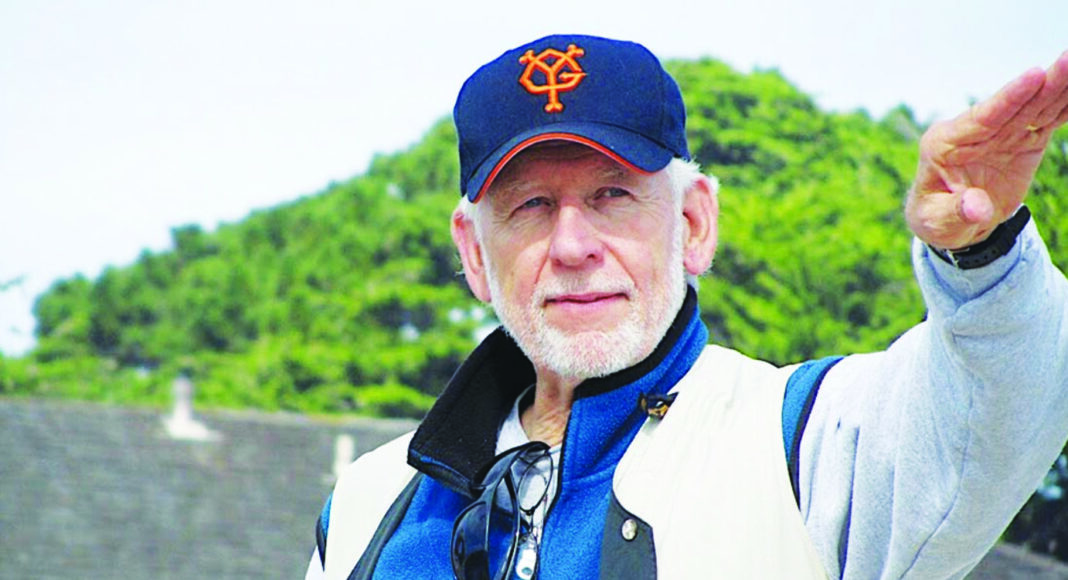

Santa Cruz County historian Sandy Lydon, who is giving his last lecture Oct. 14 at the Rio Theatre to celebrate his pending retirement, sees himself as riding a donkey facing backwards.

He doesn’t “do future,” he says, he shares the past.

His talk, titled “You Can’t Hide! Learning to Hear the History and Landscape of Calamity Cruz County,” will provide historical perspectives to help people navigate living in Santa Cruz County.

Good Times caught up with him for some pre-lecture insights.

Good Times: They say those who don’t learn history are doomed to repeat it. What should Santa Cruz learn from and not repeat?

Sandy Lydon: As with most Americans these days, Santa Cruz County residents live in a fog of hyperbole. Everything unusual that happens is “historic” or “unprecedented,” usually shouted by a TV reporter at the top of their voice. They then put the microphone in the face of a 20-something who confirms it, shouting “Never seen anything like it!”

Back in the old days, an old-timer would emerge from the smoke and, when asked, would say, “It’s happened before – back in’06, ’93, was a lot worse in ’88.”

Shiny-shoed politicians come by and anoint the moment as special – they too have short memories – and folks begin to replace it as it was before.

The community is behaving as if it has no memory, no past, no history. People want to rush back to something called normal when events suggest otherwise.

It may not make us feel special, as we’ve always been told, but it all has happened before, over and over. To behave as if it hasn’t is just plain stupid.

GT: If you could go back in time and change something in Santa Cruz’s history, what would it be and why?

SL: I believe that the Stupidest Thing Ever Done came in early 1850 when the southern county boundary was drawn down the middle of the Pajaro River. By dividing the valley in half, the state legislature created political and economic orphans on each side—Pajaro in Monterey County and Watsonville in this one.

The continuing tragedy confronted by residents of Pajaro is the result of that boundary. The recurring tragedy of the flooding in Pajaro is caused by the jurisdictional mayhem resulting from that boundary.

GT: How did you get into the history game and how did a guy from Hollister become an expert on Santa Cruz?

SL: I was a math and science whiz in high school and went to UC Davis as a pre-meteorology physics major. One of the most popular history classes was the History of the Trans-Mississippi West taught by W. Turrentine Jackson.

It was everything my Physics and Calculus classes weren’t. Along the way I began exploring Asian History and in 1961 was teaching full time (and coaching baseball) at Elk Grove High School. I was 21.

I was lucky that in 1968 Cabrillo College created a full-time history position that included Asia. And, just as Japan and China bordered on the Pacific, so does Santa Cruz. I’ve been connecting the two sides of that ocean ever since.

I also believe that it’s very difficult to explore and transmit the history of a place where one has grown up. Too many rumors, rivalries, and legends get in the way. I fight hard to stay neutral even though I have now been here for over a half-century.

GT: How do you feel about Santa Cruz’s future, particularly concerning housing and the downtown development? Are we heading in the right direction?

SL: I don’t do future. My motto continues to be “forever looking backward.” My favorite Chinese philosopher, Lao Tzu, is often depicted in paintings as riding a donkey seated looking backwards. That’s me.

The history of this place always had a floating population of people – mostly men – living on the margins. Those populations waxed and waned depending on the economics of the time. They usually lived along the railroad tracks or in river bottoms. During the deeper depressions such as the mid-1890s, it was observed that entire families were living there. Even as a Hollister kid I clearly remember there were “camps” of unhoused living in the San Benito River bottom.

What’s different here in the 21st century is our attitude towards them. The “old time” treatment was that the Sheriff would just drive them “away.” If it’s any consolation, there’s always been an economically marginalized population on the edges, challenging the community’s compassion and creativity.

GT: What should we be doing to recognize our minorities such as the indigenous people, the Chinese history, the Croatian history and others I’m missing?

SL: When I was in elementary school, America was seen as the Great Melting Pot. Immigrants came in and surrendered everything—language, culture—and emerging with nothing left but their physical appearance.

I started researching and telling the story of the Chinese immigrants in this region soon after I arrived. China was not accessible (until Nixon in 1972) so I began to explore the overseas Chinese communities. It was, in part, a painful story to tell as the anti-Chinese movement in this county was particularly vicious. It needed to be told even though the community didn’t want to hear it. Succeeding Asian immigrant groups confronted similar wrath and discrimination—the Japanese, Filipinos, South Asians, Muslims.

What I learned over the years as I explored the stories of non-Asian groups—Irish, Azoreans, Italians, Blacks, Indigenous, Latinos, Croatians , Dust Bowl—they all suffered a Fresh Off the Boat discrimination.

Perhaps if we are able to recognize it as part of our past, we might avoid it in the present. As my Harlem-born collaborator and mentor the late Tony Hill (RIP) always said, “Knowing what we know now, why don’t we start over and do it differently?”

We’re getting better at it, but the virus of racism is always here, waiting to be called forth.

GT: Tell me about the talk you are giving at the Rio. What do you want to tell people and why should they come?

SL: Good, solid, objective history was driven into hiding by Covid 19. Libraries, archives, bookstores, museums and history classrooms (mine) closed, driving those seeking any history to the Internet, that giant uncensored, un-curated restroom wall in cyberspace where the ratio of good history to rumor and fabrication is one to 99.9 %. I’m a classroom teacher and believe in the wonders that can occur when a group of eager folks is gathered together, shoulder to shoulder and LISTENING. And reacting. Aren’t many classrooms as big as the Rio Theatre.

I’m older than Joe Biden. I’m bursting with stories to tell that I believe will help attendees begin to understand how this place got this way. We’re experiencing an epidemic of community amnesia.

This is a seductive, calming place that encourages forgetfulness. Foggy mornings, seventy-degree afternoons. Hard to remember the roar of the creeks, the roar of the fires, the terror watching the lightning dance ever northward. Even harder to imagine the water table dropping until the pumps start sucking air.

We see it ass-backwards –we see the calamities as aberrations in a timeline of benign calm. It’s the other way around. The calm stretches keep the calamities from slamming together.

I picked the date of this event—Oct. 14—intentionally: just three days before the 34th anniversary of the Loma Prieta Earthquake. I plan to talk about that earthquake at the Rio. Not statistics or an interrupted baseball game, but how it affected me, the Hollister earthquake cowboy who thought he knew about earthquakes. I think about Oct. 17th every day and I hope I never forget it.

I’m gonna be the Old Timer and the History Dude. Let’s see if I’ve still got the chops.

If you go:

The lecture is Saturday, Oct. 14, 2023, 7 p.m., at the Rio Theater, $35.