Back in the 1960s and prior, steelhead trout fishing was tremendously popular in Santa Cruz. Research scientist Nate Mantua says that by one account the steelhead fishery was the second biggest tourist draw to Santa Cruz after local beaches.

“Forty years ago, people were lined up shoulder to shoulder down in the lagoon area [of the San Lorenzo River], fishing for steelhead every winter. They’d come from all over the state,” says Mantua, a scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA).

In 1965, California’s Department of Fish and Game reported a return of roughly 19,000 steelhead in the San Lorenzo River, though Mantua notes that it’s not a formal estimate, but one based on the expert opinions of local wardens and biologists.

Today, in a good year, the river supports about 2,000 fish, says Mathers Rowley, executive director of the Monterey Bay Salmon and Trout Project (MBSTP), and in a more typical year about 1,000. Recently, numbers of steelhead have dropped even below that, with an estimated 525 steelhead in the San Lorenzo for 2012-14, based on the coastal monitoring plan data set, and very low water levels due to drought are a likely culprit in the low numbers.

The steep decline in steelhead numbers—and indeed for coho salmon and chinook or king salmon (see GT’s “On the Run” 2/3) is largely attributed to habitat loss. In the case of steelhead, urbanization of the San Lorenzo Valley as well as increased water use for gardens and lawns, fine sediment from road and driveway runoff, and logjam removal—logjams actually create a healthier ecosystem for steelhead by providing cover and allowing gravel to build up, which the fish need to lay their eggs in—are the biggest factors.

In 1976, a group of local fishermen concerned about the decline of native fish populations got together to form MBSTP. Over the last 40 years, the volunteer-run group has worked to raise awareness and revive the numbers of steelhead trout, chinook salmon, and coho salmon—all once abundant in the area, and the latter of which MBSTP is most recently credited for bringing back from the brink of extinction with its hatchery work at Scotts Creek, just north of Davenport.

In 1982, MBSTP began spawning, rearing and releasing steelhead into the San Lorenzo River as part of their Steelhead Supplementation Project, which Rowley likens to an “insurance policy” for the native population of steelhead, federally listed as a “threatened” species. Last year, MBSTP released about 24,000 steelhead smolts into the river, says Chuck Backman, a board member for MBSTP who got involved after he discovered the organization’s 20-foot tank in the San Lorenzo River near his home in Paradise Park. The tank rears up to 5,000 steelhead each year, and releases them after about nine months in the tank. The rest of the smolts are spawned at the Big Creek hatchery.

“Every year varies depending on returns and what the state allows us to do,” Backman says. “We would love to get back into the 30-40,000 range for the total number of steelhead released per year.”

But this March, the MBSTP won’t be releasing a single steelhead, as the state recently put a hold on recovery efforts across the state, and is now requiring groups like the MBSTP to get permits to continue working with federally threatened or endangered species.

With the steelhead education and recovery programs on hiatus, MBSTP is focusing on raising the funds needed to secure the permit. The first step is to draft a hatchery and genetic management plan, which is a costly endeavor. “We don’t have a scientist on our staff or volunteers with scientific expertise that have time to do this, so we had to hire out really good scientists at like 100 bucks an hour,” Rowley explains.

But Rowley is confident that they should be able to restart a program similar to the one they’ve been running, which takes careful measures to ensure genetic variation by spawning only non-hatchery fish. To ensure that hatchery fish are not spawned, MBSTP takes a fin clipping of the smolt before releasing them into the river—a measure that the state hatcheries don’t necessarily take, says Backman.

The pending permitting process also means that MBSTP’s three-decade-running steelhead education program is on hold. The program, which taught 130 classrooms and about 3,000 school kids from Santa Cruz, San Mateo, Santa Clara and Monterey counties about the lifecycle and natural habitat of steelhead, involved incubating native steelhead eggs in classrooms, followed by field trips to release smolts into native streams.

The state has produced its own educational program, a scant two-page curriculum that incubates reproductively sterile, genetically engineered fish, Rowley says.

“And they can only [be released] into habitats that are sequestered from the wild, like stormwater retention ponds where the fish have a low probability of getting into the natural habitat,” says Rowley, of the state-proposed curriculum which ultimately has little to do with the actual native populations of steelhead in the wild. “And for the people in our program it’s just such a disconnect, it flies in the face of what we’re trying to do.”

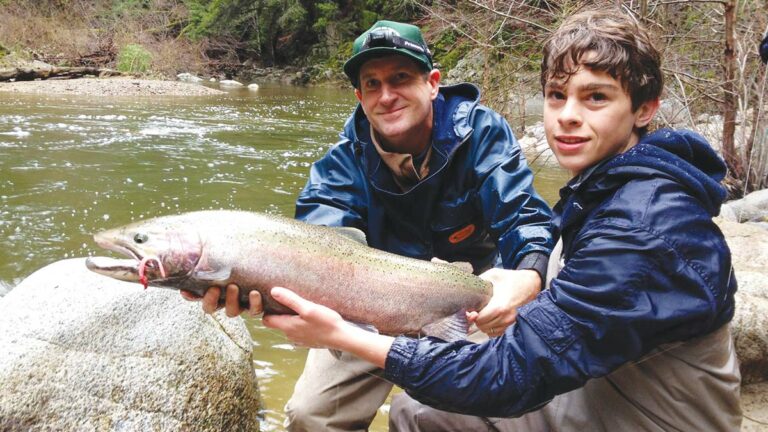

The whole point, Rowley says, is to get young people out in the natural habitat to develop a love for the river and the creatures in it—and when you see a live steelhead salmon, he says, you really get it. “They are just such beautiful creatures, full of vitality and energy,” he says. He hopes that with the new permitting, MBSTP can get its school program up and running again if it can also get its volunteers fired up.

“I think we can restart it,” he says. “The problem is the hiatus—you can’t leave a black hole in a teacher’s curriculum, they will find something else to fill it with.”

Hatch It Job

Another program MBSTP hopes to restart is its chinook salmon enhancement net pen project, which, until last year, had released young chinook salmon into the ocean from the Santa Cruz Yacht Harbor for 12 years, as a way to support California’s precarious salmon fishery. (See GT, “On the Run,” 2/3)

When the salmon released by MBSTP became adults, they swarmed back into the harbor rather than back to a Central Valley hatchery where they were born. It wasn’t long before people began showing up with their fishing rods—many of whom would not have had money to spend on a charter boat.

“You think about how wonderful it is for an 8-year-old of a farmworker family that doesn’t have that much food to catch a 35-pound chinook salmon, and provide for her family, I mean that’s a life-changing experience,” says Rowley.

It also posted successful numbers. “It worked incredibly well,” says John McManus, director of the Golden Gate Salmon Association. “The survival on those fish was about 400 percent higher than the fish that are released at the hatchery site, or probably about 300 percent higher than even the fish that are driven down in a hatchery truck to be released into the bay.”

Rowley says MBSTP is in negotiation with the Harbor and hopes to resume the program in 2017 with half as many fish—120,000—as in prior years. Last year, MBSTP pulled the plug and set up in Moss Landing instead.

“We’d always been able to bring 240,000 [fish]. The Santa Cruz Harbor started to view these fish as a liability and not as an asset, and some of our board members took that as an insult,” says Mike Baxter, board member for MBSTP. “I do love the Santa Cruz harbor and their cooperation and support. In their defense there have been negative effects of bringing the fish into the harbor. I would personally like sports people and recreational fishermen to be good stewards of the fishery and of the environment.”

MBSTP has offered to step up support services like trash receptors and potentially hire security personnel to manage the influx of people, and the litter that a few bad apples left behind. But another problem in past years was an increase in sea lions, port director Lisa Ekers says, although she ultimately supports the net-pen project.

“The last year that we had a large influx of salmon, the harbor was overrun by adult sea lions, and they were creating hazards for the boaters and presenting a danger to the public,” says Ekers. “It’s a little alarming. You look outside and see a mom with young kids and they’ll just walk up to the animals and want to touch them, so we’ve had our staff trying to keep people away. The adults range anywhere up to 4 or 500 pounds, and they do move fast.”

To find out about volunteer opportunities or to donate to MBSTP, visit mbstp.org.

There are a million reasons to love the rain. It fills our reservoirs, replenishes our soil and allows all of us to breathe just a little easier when thinking about the future of our ecosystems. But forget all that high-minded stuff—around here we’re just happy to be able to put out a Home & Garden Magazine that isn’t about the drought.

There are a million reasons to love the rain. It fills our reservoirs, replenishes our soil and allows all of us to breathe just a little easier when thinking about the future of our ecosystems. But forget all that high-minded stuff—around here we’re just happy to be able to put out a Home & Garden Magazine that isn’t about the drought.