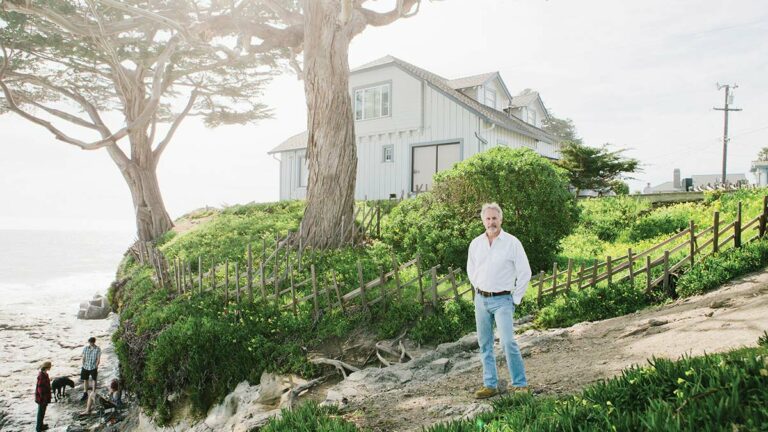

Until a couple of months ago, Charles Lester thought everything was going well at his post as the California Coastal Commission’s executive director. Lester, whose hiring was unanimously approved by the commission just four and a half years ago, had racked up a number of accomplishments as its second director ever—including securing a bigger staff, streamlining complex processes and finding compromise on controversial projects.

Looking back, Lester now sheepishly admits that he was considering asking for a raise. That was, until last December, when he got an unfavorable performance review from commissioners. Suddenly the Soquel resident realized his days at the commission, which oversees more than 1,000 miles of coastline, might be numbered.

Lester received notice of his possible termination in January and opted for a public hearing on the decision.

“The notice itself wasn’t a total surprise, although the exact timing was a little surprising,” Lester says.

Lester, who is known for being low-key and soft-spoken, is technically still employed by the commission, helping staff transition to Senior Deputy District Jack Ainsworth’s leadership, while members look for an interim executive director.

Lester’s termination set off a firestorm of environmentalist outrage, with more than 600 people showing up to his hearing in Morro Bay and giving six hours of testimony. Due to lobbyists’ growing influence on the commission, politicians and activists all over the state have said that pro-development interests were behind the firing—something Lester says appears to be true.

Commissioners, who called for the termination and approved it on a 7-5 vote, gave their own reasons for the change, some vague and some dubious.

One was the worry that the Coastal Commission staff, 95 percent of which signed a letter supporting Lester, doesn’t accurately reflect the diversity of the state. Although Lester called the accusation “a misdirection,” he doesn’t take the issue of diversity lightly.

“It’s really important. I’m not saying it isn’t. I felt like I was addressing it. Is there more to do? Yep. There’s more to do,” Lester says.

Lester had actually just released an update on the state of diversity in the Coastal Commission as part of that month’s director’s report. The report’s numbers reveal a staff that, although not a cultural melting pot, is in step with other state agencies. According to the report, the staff’s racial diversity is actually about double that of environmental groups in the state, with people of color on staff coming out to 29 percent. “By that measure, the numbers weren’t terrible. Again, they weren’t good enough, so we were working on it,” he says.

In the past few years, a discussion has been brewing that goes well beyond the Coastal Commission about a disconnect between environmental groups on the one side and diversity organizations and communities of color on the other.

The Diversity Green Institute released a report in July 2014 criticizing environmental groups across the country for having embarrassingly white staffs. Called “Green Insider’s Club,” the report examined government agencies, nonprofits and foundations. It recommended that groups institute annual diversity assessments, incorporate goals into performance evaluations and increase resources for new initiatives to work and combat this problem.

“People recognize it. It is alive and well in the nonprofit sector in general and the environmental community in particular,” says Christina Cuevas, the program director for the Community Foundation of Santa Cruz County. “They were just a little late coming to the table on that.”

The foundation, which supports many local environmental groups, has guidelines that nonprofits need to make diversity an issue, both in terms of their own make-up and in terms of the people they reach. It’s important to create environmental stewardship in historically underserved communities like Watsonville, she says. “People making decisions about programs should reflect the community so, that they understand what the community wants and needs,” says Cuevas.

For his part, Lester’s report from February had outlined steps that the Coastal Commission has been taking to change recruitment and outreach strategies. The group, for instance, has ramped up recruiting efforts in the state’s public universities. For one entry-level position, people of color in the applicant field increased to 51 percent, compared to 19 percent less than two years prior.

One of the obstacles to diversity, Lester’s report explained, might be that the coastal communities, where the commission has offices, are often less diverse, more affluent areas with a higher cost of living.

What’s at stake may go beyond the staff itself, though.

Lester feels that, in some ways, the commission works in social justice for its commitment to protecting the coast for all Californians, even those who live within inner-city communities or farther from the coast. He hopes that this focus doesn’t change under a new director, as many people have suggested it might.

“There’s a lot more work to do to building bridges to all of California’s communities, so that people can enjoy the coast more equally,” Lester says. “And that’s just something we’ll have to keep working on. Every time an access way is opened or protected, that’s a step in the right direction. Every time a prohibitive parking restriction shuts down access or somehow prevents people from getting to the beach, that’s a step backwards, and those are the kinds of things we fought against.”

Another criticism lobbed at the commission staff is that it takes too long to process applications. Lester notes that wait time for many approvals dropped significantly after the governor’s office increased its staff a few years ago. He also says that big projects sometimes warrant long waits and that sometimes it’s a developer who creates an impasse.

“You get this narrative created that somehow there’s a problem, when in fact it reflects the necessary process to make sure we’re following the law and protecting the resources as the Coastal Act states,” Lester says. “I’m not saying there aren’t cases where something could have been done more efficiently. Every once in awhile, someone drops the ball. That happens in every organization. But I think overall, if you look at the commission’s record and you look at the data, the commission’s doing a pretty good job.”

FOLLOW US

Plus Letters To the Editor

Plus Letters To the Editor