It’s tempting to call communication a lost art. But it wouldn’t be accurate. We’ve always been bad at it. These days it’s just more obvious.

The reality is, the science behind good communication is clear, proving it is indeed possible. But the trick is getting people to actually listen. This problem is fast becoming too critical to ignore.

According to an ongoing study tracking several thousand people over the past four years, political polarization tops the list of life’s most stressful experiences. It ranks even higher than the COVID pandemic, mass shootings, police brutality and climate change. This finding comes from Roxane Cohen Silver, a professor of psychological science, medicine and public health at the University of California, Irvine.

What does political polarization have to do with communication? A lot, according to one writer.

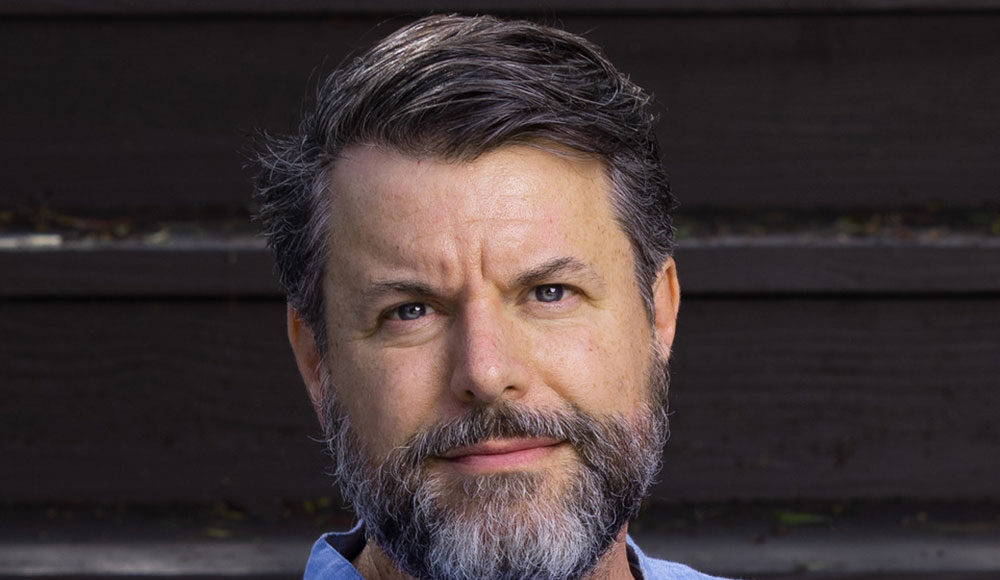

Charles Duhigg—author of The Power of Habit, a book that transformed our understanding of how to change behavioral patterns—says his latest subject is just as groundbreaking.

Describing that new book, Supercommunicators, Duhigg says, “People have been good and bad communicators throughout history. One thing is the channels have increased dramatically—there are so many more ways to do it now.

“This makes it really challenging,” he explains. “The nature of communication changes among the different channels. As new ways of communicating emerge, different versions have their own set of rules.”

Good Communication Can Be Learned

And if you don’t know the rules, you’re more likely to miscommunicate. Yet, Duhigg says, the basic principles are the same no matter the channel, and they’re rooted in emotion. No wonder a mere word or tone can generate a sleight and send a charged conversation into a tailspin.

That said, communication is a skill that can be learned. And the Santa Cruz–based Pulitzer Prize–winning investigative journalist offers a series of formulas for upskilling even the most easily tongue-tied.

And upskill we must, as we move into another contentious election season. Tensions are rising, and discussions about politics can easily devolve into shouting matches and putdowns. Or more common in polite society, people self-select into like-minded groups, forming biased generalizations about those on the other side.

But that approach is dangerous to democracy. If we can’t talk through our differences, we can’t make decisions that benefit the whole. As intimidating as this sounds to non-confrontationists, it’s the pathway to unified progress that our country sorely needs.

Duhigg believes each of us has the capacity to be a great communicator.

In his book he cites Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw’s famous line: “The single biggest problem with communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” But according to Duhigg, we have evolved to be supercommunicators—and he offers a set of skills anyone can learn.

The Three Types of Conversation

Let’s start with some basics. First off, conversations generally fall into one of three categories. Skilled communicators, Duhigg explains, have learned how to recognize, and align with, the type of conversation in play.

There is the practical conversation—What’s This Really About?—best approached by understanding what participants are looking to gain. Then there’s the emotional conversation—How Do We Feel?—where addressing inner states is essential. And finally there’s the Who Are We? conversation, when understanding group or social identity is a must.

Skilled communicators know the importance of recognizing, then matching, each kind of conversation and listening for the subtle emotions, complex needs and hidden beliefs that color so much of not only what we say but also what we hear in any discussion.

In short, there is always more to the story than the words being said, and when we understand the other person’s motivation behind the conversation, we’re much more likely to hear and be heard.

The book breaks down each of the three conversations into actionable steps for understanding. But space is limited here, so we’ll skip to the Who Are We? conversation—which is the most relevant in light of rising tensions around political polarization.

First, a question: How do you think about people with political beliefs that don’t align with yours? A Pew Research Center poll in 2022 showed that both Republicans and Democrats are increasingly critical of people in the opposing party.

Both Sides Now

And it’s not just the die-hards. Even those who lean to the Republican and Democratic parties are more likely to describe those in the opposing party as more immoral, closed-minded, unintelligent, dishonest and lazy than they were in 2016.

Duhigg writes “The Who Are We conversation is critical because our social identities exert such a powerful influence on what we say, how we hear and what we think, even when we don’t want them to. Our identities can help us find values we share or can push us into stereotypes. Sometimes, simply reminding ourselves that we all belong to multiple in-groups can shift how we speak and listen.

“The Who Are We? conversation can help us understand how the identities we choose and those imposed on us by society make us who we are,” he explains.

In a footnote, the author explains that in a heated discussion involving identities, finding common ground isn’t enough.

According to another Pew Research poll, both political parties agree that the top problems facing the country are inflation, health costs and—get this—a lack of partisan cooperation.

And on some issues, like gun control, Democrats and Republicans share more in common than most people think. Members of both parties believe in keeping the Second Amendment intact with some caveats around things like assault rifles and background checks.

Yet the sweeping rhetoric used to incite voters leads most of us to believe that there is no common ground. We get entrenched in beliefs that create assumptions, including that our own side will do what’s best for our country, and that the opposition is fundamentally flawed in their morals or reasoning.

Steps Toward Understanding

So how does one overcome the fear of approaching a hot topic with someone with an opposing opinion?

Duhigg lays it all out in a highly engaging fashion in Supercommunicators, which I’ll do my best to summarize.

First, prepare in advance. Know what you want to accomplish as a result of the discussion. Take time to recognize the likely obstacles to a calm conversation, and have a plan to manage them. Then decide if the benefits are worth the risk. If your Uncle Bob starts shouting every time he hears the name Kamala, he’s not ready for constructive dialogue and you’re unlikely to change his mind.

When you’re ready, start the conversation by acknowledging the difficulty of the issue. Knowing that someone wants to connect in a positive way can be more important than the substance. If both parties are interested in a productive conversation, establish guidelines so everyone feels heard, validated and respected. Be prepared to truly listen—a lost art Duhigg discusses in detail.

I ended my enlightening conversation with Charles Duhigg with a question of my own. Since relocating from Brooklyn to California several years ago, I wondered how the communications cultures differed.

Duhigg says things are faster in New York; people are busier and move faster. One thing he loves about Santa Cruz: It’s a welcoming and easy place to make friends. Community is important. And by learning to improve our communications skills, we’re on track to keep it that way.