I remember the smell of smoke. Or at least I think I remember it. It has been more than 50 years since that morning in the fall of 1970, but my memories of that day, and the ensuing pain and chaos—the uncertainty and deep emotional tension—remain vivid to this moment.

A steady rain was falling, the horizon gray. I recall arriving at Soquel High School (I was 15 and a sophomore) and standing at the circular base of the lower quad, huddled with a throng of close friends looking northwest of the athletic fields, just beyond the foothills to where the family of our former schoolmates, Lark and Taura Ohta, had been brutally executed and later found in the swimming pool of the Ohta home.

Rumors and speculation ran rampant. Dr. Victor Ohta, a prominent ophthalmologist in Santa Cruz; his wife, Virginia; their two sons, Derrick and Taggart; and the doctor’s medical secretary, Dorothy Cadwallader had all been bound and shot in the head, before being shoved, one by one, into the blood-saturated pool. The family home—one ridge over and less than a mile due west of my own home—had been set on fire by whomever had committed this sickening and evil act, before local firefighters arrived, discovered the slaughter and finally doused the flames.

The Ohta’s two daughters, both of whom had attended high school with us the year before, had been away at school: Taura, the oldest at 18, at an art academy in New York; and Lark, 15, at the Santa Catalina School for Girls in Monterey. By a few simple twists of fate, they had been spared the carnage and the terror.

Given the proximity to the notorious Tate and La Bianca murders in Los Angeles the summer before (the highly publicized trial was taking place at the time), the fear was that yet another freak-show cult with a Charles Manson-like figure was running loose in the Santa Cruz Mountains, and set to wreak further horror on the community.

Those fears grew into collective panic as details from the murder scene were slowly portioned out to the press. A few days later we learned that a note had been left at the crime scene declaring that:

World War 3 will begin and [be] brought to you by the people of the free universe….From this day forward and any one and?/or company of personn [sic] who misuses the natural environment or destroys same will suffer the penalty of death…[M]aterialism must die or man-kind will.

The note was dated “[H]alloween 1970,” and was signed with references to the Tarot: “Knight of Wands, Knight of Cups, Knight of Pentacles, Knight of Swords.” It wasn’t hard to jump to the conclusion that Helter Skelter was upon us.

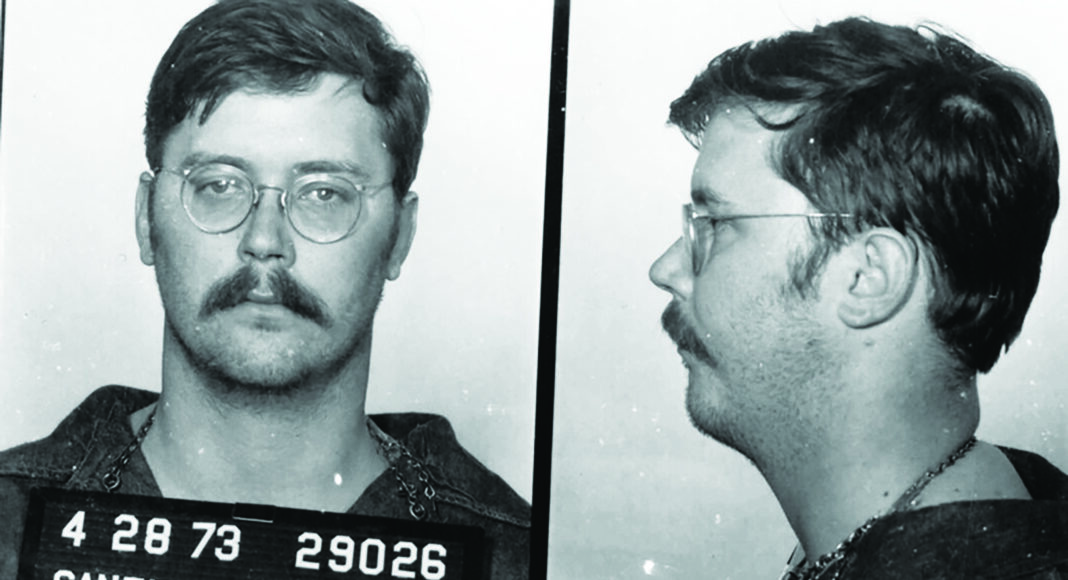

Based on tips provided by a trio of locals who knew him, John Linley Frazier—a troubled, 25-year-old mescaline addled psychopath who had grown up and lived most of his life in Soquel—was quickly identified as the principal suspect. After he had been sighted driving the Ohta’s station wagon in a variety of locations throughout the Santa Cruz Mountains, Frazier was captured by local deputies Brad Arbsland and Rod Sanford as he slept in his cabin, not far from the crime scene.

My mother, who knew Virginia Ohta, was terrified, and my father, who did business with Victor Ohta (their offices were across the street from each other’s), began to carry a concealed Chief’s Special, a .38 caliber Smith and Wesson pistol.

My dad also knew Frazier, who had worked as a mechanic at Putney & Perry’s in downtown Santa Cruz, along with other garages. From that moment on, my old man kept his pistol loaded and close by. He changed, the community changed, our lives changed. It was a dark, foreboding and transformative moment in local history.

By the time I graduated from high school in the spring of 1973, there would be 21 more murders in Santa Cruz committed by a pair of psychopathic serial killers, Herbert Mullin and Edmund Kemper. At some point in the darkness, the county’s inimitable, if ultimately tragic District Attorney Peter Chang—who would successfully oversee the prosecution of all three killers—picked up on a question asked by a San Francisco reporter and dubbed Santa Cruz “the Murder Capital of the World.”

That sobriquet went global, making its way into the pages of Time Magazine. It hung over the community for years like thick summer fog.

This grim, complex and gruesome history is the subject of Emerson Murray’s fascinating and compelling new book Murder Capital of the World: The Santa Cruz Community Looks Back at the Frazier, Mullin, and Kemper Murder Sprees of the Early 1970s.

At 552 pages, and with more than 300 accompanying photographs and assorted images—many of which have never before been published—Murray’s tome captures not only the details of the murders as never before revealed, but the lives of those who would be forever impacted by these chilling crimes. This includes family members and friends, the law enforcement and legal professionals who pursued them and, most importantly, the victims themselves, whose personal histories were often swept under the rug by beat writers working on a deadline and all-too-focused on the perpetrators rather than on those who had been killed and their families and friends left behind.

Murray has now brought them into the light. To his eternal credit, Murray has reminded us on page after page that the victims were humans, too; that they had back-stories and loved ones, dreams and ambitions. The lives that they thought were ahead of them were an essential part of the story.

Rather than impose his own narrative on these stories, Murray allows the various actors in these tragedies to tell them themselves. Using interviews, newspaper quotations, depositions, police reports and letters, Murray has assembled a patchwork quilt of oral histories (sometimes at odds with one another) that forms its own narrative and in a very real way brings the past immediately into the present.

We read the police dispatches as they happened in real time, the interviews and courtroom banter all rendered in the first-person present. The cumulative impact is stunning. Murder Capital of the World grips the reader on every page.

Raised in Santa Cruz County, and a graduate of San Lorenzo Valley High School, Murray had the story of the mass murders driven into his psyche his entire childhood. It was part of the valley’s cultural milieu.

Born in 1973, just as Kemper and Mullin ended their killing sprees, Murray also had a direct link to the events. Murray’s father, Roger, had been a roommate and close friend of one of Mullin’s victims, Jim Gianera. The book includes a picture of Murray’s dad, Gianera and another friend.

Murray also has another familial link to the story of the crimes. His grandmother, he recalls, “collected unusual and sometimes morbid newspaper clippings. I can remember looking at clippings from the Ohta-Cadwallader murders at her house when I was very young.”

References to the era remained constant. “As I grew up,” he says, “I remember my parents’ friends talking about these crimes at parties and dinners. It just feels like it was all around. It always felt important. I really can’t remember when, but when I was very young, I just started collecting newspaper clippings about these crimes myself. “

It all led to something of an Edgar Allan Poe-like childhood for Murray. “My brother and I used to hang out with our neighbors under the streetlight and tell Herbert Mullin horror stories as kids. Logically, we knew he was in prison, but he was still like the boogeyman to us … He haunted us.”

As Murray grew older, he was startled by how the community had effectively buried this history. He was also surprised when he realized that there had been no major works about the murders told from a local perspective. He felt that this significant history was dying, that it was about to be lost forever.

Then, three years ago, he and his wife attended a talk on Kemper given by a pair of retired local law enforcement figures, Sheriff’s detective Mickey Aluffi and retired Judge William “Bill” Kelsay, who had worked in the District Attorney’s office with Chang.

“Mickey’s memory was sharp and clear,” Murray recalls, “but the audience was all older, and I panicked that these first-person stories would be lost in the next decade or two. I started working on the book the next day.”

One significant aspect of this story that has long been overlooked is the heightened community tension that ensued both during and in the aftermath of the murders. Murray delves deep into the subject.

It is equally critical to note that this was a time of global violence. The U.S. had unleashed a technological carnage on the peoples of Southeast Asia, and that genocide was replayed daily on the nightly news here at home. Demonstrations, police violence and political assassinations had all become routine, even normalized. Violence beget violence.

Little more than a year after Frazier had been convicted of the Ohta and Cadwallader murders, a series of seemingly unrelated killings started taking place again throughout the county and in other communities in Northern California.

The 6’9″ giant Edmund Kemper III—who had been convicted in 1964 of killing his grandparents when he was 15—prayed on young women hitchhikers, often sexually abusing their corpses, and perhaps even engaging in cannibalism. He finally killed his mother, Clarnell Strandberg, with whom he was living at the time of his murder spree, and one of her friends, Sara “Sally” Hallett.

Herbert Mullin, who had spent his adolescence and early adulthood in the San Lorenzo Valley, began hearing voices telling him he needed to kill in order to save the region from earthquakes. It is believed he killed at least 13 victims during his reign of terror.

Once again, the murders hit close to home.

On the evening of February 13, 1973, after returning home in the evening from baseball practice at Soquel High, I received an erratic, terrorized call from my mother who said that our family’s lifelong friend Fred Perez, a beloved working-class Santa Cruz icon, had been shot on Gharkey Street, just kitty-corner from my aunt and uncle’s house. My aunt Joan Stagnaro had spotted the killer’s car and identified a telling “STP” sticker on its bumper.

It was Mullin she had spotted. He had shot the 72-year-old Perez, who was working in his yard, through the heart with a .22 rifle. Because of my aunt’s quick response, Mullin was arrested a short time later. I was startled to discover that my aunt’s “voice” recounting these critical events found its way into these pages—she died 34 years ago—but Murray had uncovered it in the form of depositions and court testimony.

Kemper turned himself in two months later, in Pueblo, Colorado.

If only that were the end of it. In the mid-’70s, Richard “Blue” Sommerhalder (who killed Vickie Bezore, the wife of seminal Santa Cruz journalist and editor Buz Bezore) and the so-called “Trailside Killer” David Carpenter would commit multiple murders here again.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Joan Didion observed at the beginning of The White Album, her brilliant series of essays on the Manson murders and the often-violent excesses of California culture in the ’60s and ’70s. “We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five.”

As I worked my way through Murray’s book, I found myself a long way from any moral lessons. Indeed, my blood boiled on many pages as I read the killers’ own recounting of their savagery and the lives they destroyed. In due candor, there were certain passages I chose to avoid. In other instances, I found myself shaken, often to the point of tears.

If there is a glimmer of light in all of this, it is in Murray’s commitment to honor the life of those who were slaughtered, as well as their families. The most moving of these testimonies came from my former classmate Lark Ohta, who lost her family more than a half-century ago, and whose sister Taura committed suicide seven years later. In many ways, Lark serves as the deep conscience of the book.

Last week, with Murray serving as a facilitator, Lark and I touched base for the first time in 52 years. She talked about the positive experience of working with Murray and doing “whatever I could to bring my family to life and to describe the town that they loved.”

She recalled growing up on the West Side, of attending Holy Cross Elementary School and of the magic place Santa Cruz was in the 1960s. She recalled the Pacific Garden Mall and the wharf and Holy Cross Church. She remembered her mother double-parking in front of Dell Williams Jewelers, and her father buying her the Beatles’ White Album.

“We lived a perfect and happy life,” she said, “in a quiet and very cool town.”

Lark’s most powerful statement, however, was about the man who killed her mother, father, two brothers and close family friend—and, really, her sister as well. “I forgive Frazier,” she told me, “as I believe he was a broken human being. No healthy person could kill a child.”

No anger. No bitterness.

“I miss my family and my home,” she concluded. “I grew up in Santa Cruz in a special time, and no one can make that bad for me. It was my home … I will always love Santa Cruz.”

‘MURDER CAPITAL OF THE WORLD’ BOOK EVENT

Bookshop Santa Cruz will hold a virtual event this Thursday, March 31, featuring Emerson Murray and his book Murder Capital of the World: The Santa Cruz Community Looks Back at the Frazier, Mullin, and Kemper Murder Sprees of the Early 1970s, at 6pm. Free registration: bookshopsantacruz.com/emerson-murray.

Wow! I can’t believe what I am reading. I went to Holy Cross Elementary as well as High School and I used to walk home from school, up High Street with Lark since my family lived on Majors Street near West Lake and Lark lived not far from me. Lark was a class mate and a go-between for my first girlfriend Mary Kester(at least we thought we were boyfriend and girl friend when we were 9 and 10). Lark was so smart and very nice to me and I often think of her and where she ended up. Coincidently my wife and I are flying out tomorrow to SFO then Santa Cruz and renting a house on West Cliff Drive to visit old school friends and catch with my large Russell family. I was searching through Good Times to see what was happening next week in Santa Cruz when we are in town, when I came across this article. I have chills down my spine and this brings back so many memories. If there is a way to pass this on to Lark, please do and tell her I miss her. God Bless, Kevin Russell

My name is Dave Lindsay and I was raised in san jose I do remember in the early 70s. My parents speaking of those brutal killings.

And recently a good friend of mine Bought the house right next door The house was vacant for several years. Before my friend bought it I guess they had a hard time selling the home because of the history next door.

I haven’t talked to my friend recently but I would like to find out if he’s seen any signs of haunting it’s a sad story

Geez, I came across this piece while

reading The Guardian’s story on the making of The Lost Boys. When Santa Cruz came up as the ‘Murder Capitol’ I thought it was crazy! I lived in Santa Cruz in the 60’s, GED N. Santa Cruz High ’66..lived on Water St., worked for Neighborhood Youth Corps..drank coffee on grey winter days at Coconut Grove..great town and mellow memories. I left before all this violence happened, what a shock to read this brilliantly written piece, and the birth of the book! I appreciate the true recording of these poignant stories. My gratitude to you All.

That’s just horrendous and all a result of the terrible gun culture in the US. When will it all end? How many more hundreds and thousands have to die as a result of this?

Nice try, Mullins and Kemper both used knives to kill several of their victims. Kemper was especially fond of dispatching his victims with his bare hands. Firearms are ones only real protection against psychos. Perhaps if Dr. Victor Ohta had a firearm his family would still be alive.

Touche!!

I’m glag you clarified what shouldn’t have to be.