The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it. —Karl Marx, Theses on Feuerbach, #11, 1845

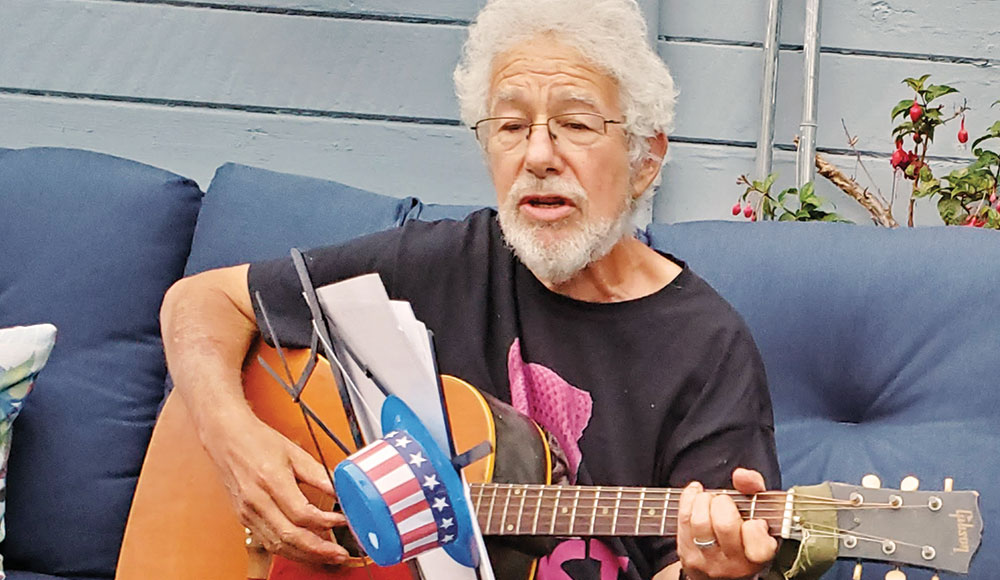

The loss of Mike Rotkin—former mayor of Santa Cruz, key figure in the Community Studies program at UCSC, a civil rights advocate and practitioner of civil disobedience, husband, father, friend, mentor, Marxist, humanist, feminist, musician, outdoorsman, environmentalist, transportation guru, basketball and softball player, shape-shifter, ad infinitum—has been felt throughout the community since he passed away last week from an arduous battle with leukemia. He was 79.

Let me be candid and direct: the news hit me like a truck. We had been friends and colleagues and comrades for more than 50 years—I first met him in my late teens when I was working as a fish cutter on the Santa Cruz Wharf—and few people in that half-century have had the type of profound and long-lasting impact on my life as he did.

I was certainly not alone. I have been hearing it throughout the community, from all quarters, from people of all ages and all walks of life. He was an extremely kind and civil man, thoughtful, bright, committed and humorous. Seemingly ubiquitous. And hard-working. Fucking hard-working. I am not sure he ever slept.

When I ran into Mayor Fred Keeley last week on the Santa Cruz Wharf (ironically not more than 30 yards away from where I had first met Rotkin), I mentioned Mike’s death, and Keeley responded ebulliently and emphatically, “Wasn’t he a great guy? He was a great guy!” He then went on to tell a colorful story about traveling to L.A. with Rotkin just as the Rodney King riots were hitting in the spring of 1992. The story perfectly revealed Rotkin’s subtle yet devilish sense of humor (you can ask Keeley for the punchline). Mike was a jokester at heart, always upbeat and occasionally devilish, with a persistent beatific smile on his face.

These last few days, I have been reading Sarah Rabkin’s superb and fascinating oral history of Rotkin, “On the Rise and Fall of Community Studies at UCSC, 1969-2010” (available online at escholarship.org). It’s an engaging 450-page document. I dare say that Mike comes back to life as you immerse yourself in this remarkable interview. I could actually hear his voice and his chuckling throughout.

What comes across in a rather striking manner are the ways in which Mike came to his politics as a young adult (not really in his teenage years, as I presumed). Mike’s was an American Graffiti childhood (he graduated high school in 1963), in which he was in the marching band (he played a variety of instruments) and a rather mediocre and uninspired student. It wasn’t until he served as a social worker and community activist in the rural South that he found his political passion and direction.

Most guys I grew up with were frustrated jocks. Mike was a decent (albeit enthusiastic) athlete (we were teammates on a campus softball team in the ’80s) but he was actually a frustrated Eagle Scout. That’s right. The great Marxist radical’s adolescent failure was not attaining the top rank in the Boy Scouts as an “Eagle.”

Several years ago Mike set it up so that his parents, Irv and Esther (absolutely delightful, smart-as-hell, liberal, relocated New Yorkers with quick tongues), enrolled in a two-day program on Santa Cruz County history I was teaching at the Monte Toyon Camp and Conference Center in the Santa Cruz Mountains. They were absolutely wonderful, clearly loving and adoring of their son, but Esther couldn’t help but tell me the story about how she kept Mike from achieving his dream of becoming an Eagle because she wouldn’t sign off on him being a “good citizen” at home. “I think he’s held it against me ever since,” she said. “But I think it was good for him.”

When Mike first ran for the Santa Cruz City Council in 1979, along with Bruce Van Allen, he did so as a socialist-feminist (a great distinction from the Goldwater-loving conservatives who dominated the council in the post-World War II era). Indeed, Mike was best known in his early years on campus for teaching an “Introduction to Marxism” class (in which I once served as a teaching assistant) that was always packed and which he taught for decades.

Mike was what I would call a practical, or pragmatic, Marxist. He preferred the early canon, the humanist Marx, though he also embraced Marx’s criticism of capital structures. In the aftermath of the 1989 earthquake, after he had served on the council for many years (and by then had been mayor more than once), he broke with many of his former colleagues because he felt economic development was a necessity for sustaining the municipal enterprise (the City of Santa Cruz) that he and his progressive colleagues were now overseeing.

I am blessed with a lifetime of memories of Mike and I will have lots more to process once I finish this brief tribute to his memory. During a protest at UCSC in the early 1980s (in which he and I were both arrested and bused to the police station downtown), I angrily (and perhaps threateningly) confronted UCSC chancellor Robert Sinsheimer. Mike took me aside. He agreed with my position but he chastised me about my style. He thought it was ineffective and counter-productive. And being ineffective was not part of Mike’s political vocabulary.

Looking back, I don’t ever remember Mike angry. Firm and assertive, yes. Argumentative, sure. Angry, no. It wasn’t his style. It wasn’t who he was—neither as a person, nor as an activist or elected official.

Mike was a radical but he most often took the high road. He was a fierce and competitive debator in a political skirmish, but there were lines he didn’t cross. Even when he disagreed with you (and he and I had our moments), he was considerate—passionate without being overly confrontational. And more often than not he prevailed.

In his oral history with Rabkin (again, I encourage you to read it), Mike looked back on his truly protean and far-reaching career. “I’m a very fortunate person,” he declared, “that I did what I love doing, I got paid well for it, more than comfortably for it, and was able to integrate the different things that I did…So I [found] it challenging, and exciting, and fun work. I’ve never been bored, since I moved to Santa Cruz in 1969, for five minutes in my entire life, I have to say. So—it’s worked out well for me.”

Much of what we think of as “Santa Cruz”—from our community’s vast array of social programs, the Greenbelt, pay equity, and on and on—are, and will remain, a reflection of Mike’s work. His loss is painful, even staggering, but his legacy here is vast and will be long-lived.

Mike Rokin is survived by his beloved wife of three decades, Madelyn McCaul, and stepchildren Phillip Greensite, Jesse Mantonak and Jarel Chavez (Octavio). There is a GofundMe page set up to fund a bench in his honor along West Cliff Drive. A celebration of his life will be held on what would have been his 80th birthday, on Sept. 17.

Mike Rotkin was not a long shadow, but a BRIGHT LIGHT for this county. God bless him. He helped bring this county out of its dark RETHUGLICAN past, and into the progressive sunshine. so glad i got to know him.

When I enrolled as an undergraduate at UCSC, I met Mike Rutkin and immediately made community studies my second major along with environmental studies. It was the mid 70s and UCSC was still the new campus in the UC system complete with its no grades and no intercollegiate athletic teams. I loved it there and Credit three professors at UCSC for redirecting my intellectual interests, political, leanings, and even identity. Those were Claudia Carr, Mike Rotkin, and Alan Sable.