Christopher Moore’s latest New York Times best-seller, Anima Rising, is his 19th novel. And it is not better or worse than those that came before, but is an equally unique, brilliant work of art. Yet, that doesn’t really get to the kernel, or near the sum of the totality, of Moore’s prolific output.

In other words, it’s difficult to dovetail Moore into a distinct category. Bookstores and libraries hinge on this kind of ill-conceived convenience, but sometimes it even works in an author’s favor. “I was lucky to be shelved with general fiction rather than with genre fiction,” says Moore from his home in San Francisco. “I think it’s helped my career more than anything. I might have perished if I had been put on the dragons and elves shelves. And while certainly some of my books would fit there, I think that the books gained a wider audience because I wasn’t.”

If you search AI, as if you have a choice, Moore’s work, his oeuvre, if you will, is readily processed as absurdist fiction, which is absurd. That is, if you know anything about absurdism in literature, which apparently AI and reviewers do not, but Moore does.

“That’s just a symptom of people not being able to really pigeonhole me,” Moore says. “So they use that as a term. I don’t reject it, and I don’t adopt it. If you look at the real absurdists, like Alfred Jarry, from the turn of the century, and stuff like that, I don’t fit into that genre.”

So where does Moore fit in? In my opinion, Christopher Moore is one of America’s not-sung-enough, top-tier “absurdist fiction” writers. Following the footprints in the Isles sand of British writers like Terry Pratchett, who sadly passed in 2015, and Neil Gaiman, who has been unceremoniously dethroned, and beloved American author Tom Robbins, who left us earlier this year, it’s time for Moore to take the heavyweight title. And his latest, Anima Rising is a contender for the crown.

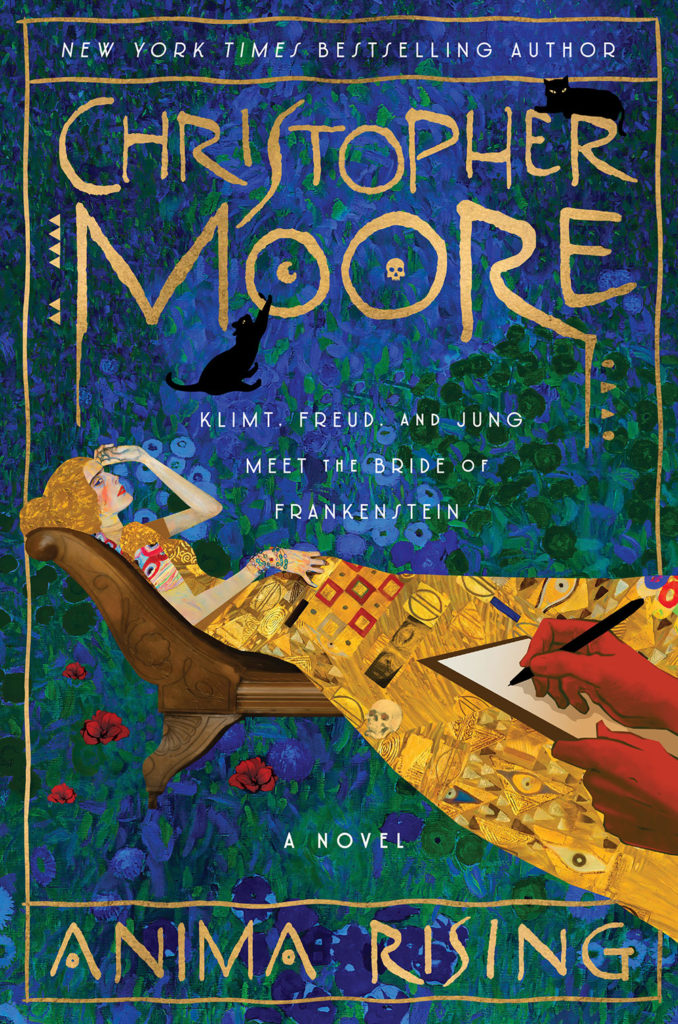

Imagine Vienna in 1911. It’s a heady time. Gustav Klimt, painter of such well-known beatific, glimmering paintings as The Kiss, is very happy, holed up in his studio, with models both ethereal and oddly supernatural.

Klimt by all accounts is a kind man, who loves life, though many details shared in Anima Rising come from inference. “Klimt didn’t write about, or talk about, his art or his life. And so everything had to be gleaned from other people’s impressions of him. Fortunately, there are a lot of photos of him, having fun with his friends and so forth.That informed how I created the character and fleshed him out. It was a disadvantage that he wasn’t analytical about his own work and when asked about it, he said ‘everything you need to know about me, you can get by looking at my paintings. And the only thing I’m interested in is people, and specifically women, and that’s that.’ The character that I wrote makes Klimt seem like a very affable guy who enjoys life. Vibrant,” Moore says.

As you learn, in Moore’s sage afterword, Vienna at the turn of the century was a “genius cluster,” chock full of wildly influential couch doctors like Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, symphonic gurus like Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss, and a host of (soon to be) renowned architects, (evil) world leaders, and of course artists. It’s in this landscape Moore composed one his most laugh-out-loud funniest books, and true to form, brimming with a Mandelbrot of smaller characters.

This seamless blend of unique historical people and factoids comes, mostly, from the exceptional imagination of Moore. Even the minor characters resonate with an observable humanity, rarely given the detail, in such short passages, in any modern literature. “I had a good teacher, who basically emphasized that all good writing, all good fiction, was going to be based on character. And so I always pay attention to that, even if the character only has a few lines. I polished and learned [how to do this] when I was writing Lamb [2002] because there are twelve apostles, and probably four or five that don’t even have a line in the Gospels. They don’t say a word. They’re just names. I had to create everything else from that,” Moore relates.

For Moore fans, there are burning questions about a sequel to Lamb (not going to happen), and when a film adaptation is coming for any of the 19 novels. And maybe that transference of novel to screen is just what might push Moore into the center of the attention economy—but will fans be happy with cinematic adaptations of their still-underground favorite bestseller’s novels?

Don’t worry, fans—Moore knows what he’s doing. “You are either going to take the money and give up control, or you’re not going to take the money,” Moore dispenses. “The decision is made on the day that you do it. Am I happy that Disney has shelved my first novel (Practical Demonkeeping) for 35 years? Nope. Was I happy to go from being a waiter to a full-time writer overnight? Absolutely. And those are the kind of decisions that I’ll have to make when the opportunities come.”

Christopher Moore speaks at 7pm on June 17 at London Nelson Community Center, 301 Center St, Santa Cruz. Tickets: $37–$47 (includes book) at bookshopsantacruz.com.

I would love to go to Christopher’s talk, but I already bought a copy of his book – I pre-ordered it as soon as I was able to do so – and there is no option for attending without purchasing a copy of the book.