The first buzzed-about novel of the 2020s has no overt Santa Cruz themes or references. But the subtext? That’s a different story.

Miranda Popkey’s newly released Topics of Conversation is a debut novel composed of a series of fictional encounters between an unnamed narrator and several other women over the course of 17 years. And those conversations and anecdotes always seem to lead, whether obliquely or explicitly, to themes of female desire, infidelity, violence, and victimization at the hands of predatory men. Whether it was meant to or not, the book will be seen as an uncomfortable if bracingly honest documentation of #MeToo disclosure.

The book is set, in part, in California—but in Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, San Francisco, and Fresno. There are no references to Boardwalk rides or banana slugs.

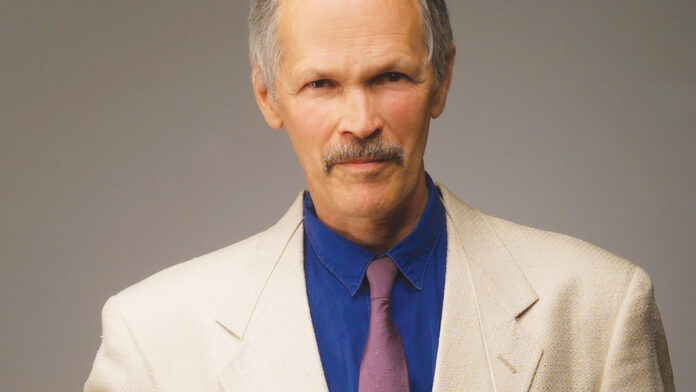

The subtext comes from the 32-year-old novelist herself. Though she claims no one would ever guess it, Popkey is Santa Cruz County born-and-raised. And if her new book has any sense of restless spiritual dislocation to it, that may have started in her childhood.

“I think I had a feeling growing up that I was emotionally out of sync with Santa Cruz,” she says. “There is an easygoing vibe that the city has. But I’ve always been a little tighter-wound than your average Santa Cruz resident. I don’t surf. I don’t like to go to the beach. A lot of my adolescence was spent trying to figure out how I felt in relation to the place I grew up.”

Popkey, who now lives in Massachusetts, grew up in a series of homes with one divorced parent or the other, mostly in Ben Lomond and Bonny Doon. She graduated from Pacific Collegiate School in 2005. And at the age of 18, she left Santa Cruz for good.

Of the San Lorenzo Valley in particular, she says, “It’s a magical place. But there’s light magic, and then there’s dark magic.”

Popkey comes to Bookshop Santa Cruz on Jan. 16 to celebrate the release of Topics. If her attitude toward her hometown is ambivalent, her feelings toward Bookshop are much less complicated. “It’s incredible honor to read at Bookshop, which was one of my favorite places to spend time growing up.”

Regardless of her complex relationship with Santa Cruz, her return is triumphant, thanks to the new book, which has been well-received in media reviews across the country. There have been interviews on NPR, and recommendations from Time magazine, the Boston Globe, the New York Times, and other outlets.

The themes of the book—most vividly, how women are socialized to adapt to the demands of men—have been percolating with Popkey for most of her adult life. But she was just beginning to write some of the short stories that eventually became Topics when the revelations about predatory Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein first came to light in 2017.

“That was a big moment in unlocking what I wanted to write about, thinking about the kind of people who have been in control of our popular culture,” she says. “I thought about how far-reaching that really was, most horrifically for the women who were assaulted and raped, and whose life trajectories were changed by the fact that they had a single interaction with a man who had a great deal more power than they did—but also in the way that the women who watched the movies he produced were changed in smaller but not insignificant ways.”

Topics is notable not only for its themes, but also its narrative style. It is written in a kind of hyper-realistic adherence to the way people really speak, complete with conversational misdirections, weaponized bluntness, and the shorthand of intimacy.

“I wanted it to sound like people talk,” she says.

She credits listening to a lot of first-hand podcasts, particularly one from psychotherapist Esther Perel, for helping her internalize the natural rhythms of her prose.

Popkey says that growing up, her inclination as a writer was not toward fiction, but instead toward analytical writing. But she has found in fiction a basis for self-discovery.

“I always thought that if I ever wrote a novel, it would be embarrassingly autobiographical. The truth is every single feeling that is in this novel is a feeling that I have had, but nothing in the novel actually happened to me or anyone I know in the way [described in the novel].”

Her fish-out-of-water state of mind growing up may have sharpened her writer’s sense of empathy and self-awareness. But that sense of dislocation is part of her life still. In fact, she began writing the novel while staying at her mother’s house in Santa Cruz County.

“California is the place I’m from,” she says, “and it is part of my identity. It’s this problem that I’ve been trying to solve: I’m from California, but I don’t really seem like I am. But the older I get, the more the California comes out in me.”