How the Santa Cruz County Veterans Memorial Building continues to serve the community

It’s 10am on a Wednesday morning and the basement of the downtown Santa Cruz County Veterans Memorial Building (SCCVMB, or as locals know it, the Vets Hall) is teeming with energy. Roughly a dozen people are moving about, wiping down tables, mopping the floor, making coffee and prepping food for the unknown number of veterans about to arrive.

Lined against the right wall are multiple large boxes and crates filled with onions, potatoes, lettuce, bananas, cauliflower and other fresh produce, including dragon fruit. On one side of the produce table is a pantry fully stocked with bread, condiments and cans of beans, tomatoes and soup. On the other side is a full working kitchen with volunteer Dixie LaFave eagerly dressing a large pan of salad.

Hanging on the walls circling the room hangs the state flag along with other colors representing different branches of the military and Santa Cruz units that have served in wars dating back a century.

Volunteer and de facto kitchen manager, Mark Gagne, puts the finishing touches on tables and answers volunteer questions. For the last six months he’s volunteered weekly at the kitchen, with a history of past volunteer service and 23 years in the Bay Area restaurant industry.

“It’s the team,” he says. “If we didn’t have a team of great people volunteering we couldn’t do this.”

In a few minutes, the Vets Hall’s free lunch and pantry service will begin and 79 vets, young and old, will pass through the doors for a hot meal and two bags of groceries. On any given week, everything from pizza and lasagna to tri-tip with sides might be served. The food is donated by Second Harvest Food Bank, Costco and Oroweat Bread. It’s a service held every Wednesday, even during the days of the 2020 lockdowns.

“Even though there were only 20 vets that were showing up, these were people who needed that pantry,” remembers Building Manager, David Pedley.

“So we did to-go meals the whole time.”

Pedley has been the building’s manager for the past two years, previously supervising the COVID emergency shelter for a year and a half. He’s one of the Vets Hall’s many success stories in recent years because prior to COVID, he was one of the 40,401 homeless veterans nationwide. Now he’s part of the driving force for the Vets Hall’s renaissance moment.

“I just came in and started asking questions, then did the whole program,” Pedley says. “Now I run the place and have a second baby on the way.”

For half a century, the downtown Vets Hall has played an important role in the lives of those who have served. A gathering place for veterans to get back on their feet, utilize resources or just have a good laugh with friends.

Veterans like Joe Biondo, who served in the Navy in the 1970s.

“The economy has become so top heavy that we need things like food stamps and services,” he says.

“This luncheon probably saves me $40 a month and the pantry at least another $50.”

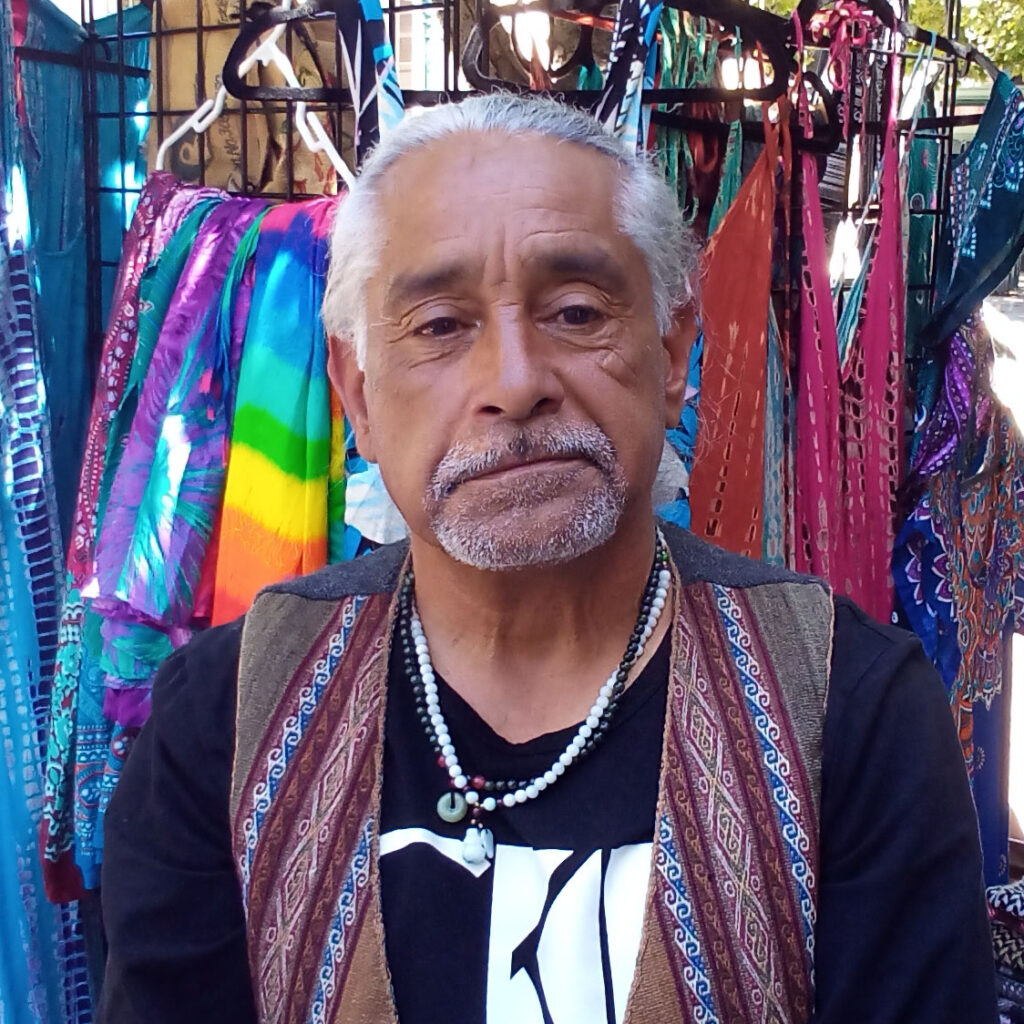

Santiago Calderon, a Vietnam veteran who also served in the Navy, says he wasn’t aware of how many services were open to vets before coming to the SCCVMB.

“I came here and went, ‘Wow! This is great,’” remembers Calderon. “It’s helped me help others.”

Each week he volunteers his time cleaning up the basement hall after the food service has ended.

“I tell everybody this is a great place,” he says. “There are a lot of services here.”

Along with the hot meal and food pantry, each Wednesday, veterans can utilize services from doctors and counselors, the Rotary Club of Santa Cruz, American Legion, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the United Veterans Council, the United States Department of Urban Development Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) and more. It’s an easy one-stop for veterans to get back on their feet or continue down a prosperous path.

They even host holistic and mindfulness classes for the vets along with computer skill classes to keep them competitive in the job market.

Yet throughout its history, the SCCVMB has also been a cornerstone in the Santa Cruz community. A dance hall that opened to big bands and jazz, it now hosts punk, metal and hip hop concerts with national—and international—acts. A community center that hosts classes from dance and yoga to fencing, meditation and recovery meetings.

“We have the most amount of NAs (Narcotics Anonymous) and AAs (Alcoholics Anonymous) in one place in the tri-county area,” Pedley says.

Rent paid by the classes, meetings, concerts and concessions all go back to the Vets Hall so it can continue to grow its mission helping one veteran at a time.

“The whole model of our nonprofit is using the Veterans Memorial Building to generate revenue and then turning around and using that profit to provide services for veterans in the area,” explains Executive Director Chris Cottingham.

As the Executive Director for the past three years and the Director of Service and Operations a year before that, Cottingham is one of the main people leading the Veterans Memorial building into a new era.

“The model of using it as a community space, then having that continue to give back to the community, is very sustainable,” he explains.

“Because the bigger we get means we’re doing more for our community.”

REMEMBERING THE PAST

The Santa Cruz County Veterans Memorial Building was built in 1932 at the behest of the public, the American Legion, the Civil War veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic, the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the veterans of the Spanish American War.

Completed in September of that year, it was originally slated to be built where it stands today—next to the downtown Post Office. However it was almost built “on wide grounds” at Laurel Street and Pacific Avenue to “be used in part if not mainly as a civic auditorium,” according to a May 8, 1930 issue of the defunct Santa Cruz News. The veterans fought against this idea and eventually won to keep the original location.

The purchase cost $2,000 less than estimated and the remainder of the money was used to build the World War I memorial statue that stands at the head of Pacific Ave., across from the SCCVMB.

According to the National Register of Historic Places its “heyday” was primarily in the 1930s and 1940s “when local peace-time efforts were geared toward recovery from the Depression, creation of a strong community solidarity and building a sound economic base.” But throughout its 91 years the Vets Hall’s primary purpose is to serve as a central meeting place for veterans, their groups and service providers.

“Anytime you have something that’s been around for that many generations, you get all these different stories,” Cottingham says. “It’s like the original social network.”

During the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake, SCCVMB served as an emergency shelter but closed in 2010 due to much needed renovations and mismanagement. Four years later it reopened but this time a strict, “no live concerts” rule was placed on the building. It wouldn’t be lifted until Cottingham was hired in 2019.

With a quarter of a century of experience in the music industry under his belt, Cottingham saw the building’s potential when he was doing a photoshoot with Salinas reggae band The Rudians. When he was hired, one of his first acts was to bring back the music scene. However, the SCCVMB only hosted a couple of concerts before the 2020 COVID pandemic lockdowns went into full effect.

However, that was just the beginning of the Vets Hall’s next transformation.

“During the pandemic, we were the first emergency shelter to open in the community,” Cottingham remembers. “The word came out on a Tuesday or Wednesday that everything was shut down and by that Friday we were open.

Over a 16 month course, the Vets Hall was home to 45 at-risk individuals who were elderly, houseless, veterans or all three. It also housed families and evacuees of the CZU Lightning Complex Fire.

During that time, staff grew to 40 employees to accommodate social distancing while providing shelter, food and activities to residents. Some local restaurants and organizations would contribute groceries or cooked meals so the shelter could continue providing for emergency residents and veterans in need.

The SCCVMB also provided a “Zoom room” for anyone at the shelter to use for recovery programs, counseling and keeping in touch with the outside world. The Vets Hall took the pandemic as an opportunity to renovate their outdoor courtyard for meetings and activities as well.

“It used to look like this god-awful Zen garden that wasn’t taken care of,” laughs Pedley.

Now it’s a memorial courtyard with curated flowerbeds and paved in bricks with the names of veterans deceased and alive, including Pedley.

Yet, one of the biggest ways the SCCVMB pivoted during those 16 months is how it connected with veterans and civilians living in tents along the levee, in parks or under bridges. Staff saw how, by providing individuals with shelter, food and a place to receive mail, they were often able to save up some money to a point where they would be back on their feet. The Vets Hall would then step in and help connect them to different housing organizations, banks and employment opportunities.

“We had an option,” says Cottingham. “We could either be dark or run at the problem and be a part of the solution.”

Staff also asked around about what are the top ten items people experiencing homelessness needed. They were shocked to find out the number one requested item was a first aid kit.

“Everyone seems to think that socks are the most important thing,” Cottingham says. “What an ‘aha’ moment!”

That data led to the SCCVMB’s Community Aid Resource Effort—or CARE—Package Program in which Cottingham says they passed out over 300 packages to people on the streets that included first aid kits, solar chargers, hygiene bags and other essentials. As people transitioned into housing, the SCCVMB raised money for what Cottingham calls “move-in kits” with household items like curtains, dining ware, mattresses, cleaning products and more. They even helped ship and move new furniture for the newly housed.

“That experience of running the shelter is ultimately what inspired us to move onto the Village,” he admits.

Housing First

It’s a beautifully warm Tuesday morning in the redwoods of Ben Lomond. Besides the passing traffic, the air is peaceful and serene among the ten red cabins dotted along the hillside. Each one contains a living room, television, separate kitchen, refrigerator, light fixtures, bathroom and separate bedroom with a mattress.

“We are a housing first program,” explains Keith Collins. He’s the SCCVMB’s Program Director for their Veterans Village of Santa Cruz County, a housing community exclusively for veterans.

Opened in February of last year, the land for the Vets Village was purchased using independently raised funds, not government money. A few months later they were awarded an additional $6.4 million from the state’s Project Homekey grant funding to expand and renovate the campus. They are projected to have an additional 11 units added to the property equaling 21 units with 25 bedrooms and 23 bathrooms for a total of 24 individuals onsite.

All of the furniture and appliances, including office furniture at the Village and at the SCCVMB, is donated by Grey Bears Thrift Store.

“The biggest challenge has been getting the construction approved and completed,” Collins says. “There was a delay because of the floods and rains that really set us back.”

“In fact, the road in front [of the property] is still being repaired because of the floods,” says SCCVMB caseworker, Tamiko Collins.

Currently the property is housing six groups of vets and families for a total of 13 people. With a $100,000 grant for transportation awarded by the Monterey Peninsula Foundation—which holds the yearly Pebble Beach Pro-Am—the Village bought a van for transporting the residents for grocery shopping, events and to utilize the weekly services at the SCCVMB.

Of the six acres that the property sits on, only three of them are actually buildable. This allows the Village to utilize its unique forest setting and keep to their—and the veterans’—mission statement to serve.

“We’re currently raising funds to build a serenity trail,” Keith says. “That would be not only for our Village but the entire surrounding community as well.”

As with the SCCVMB’s courtyard, the trail will contain landmarks and memorial bricks to recognize all in Santa Cruz County who have served.

“And a community garden,” smiles Tamiko. “People like hiking up there already so we want to build the trails and make it a fun place to bring your kids and learn.”

The Collins’, who are married, say the Village couldn’t have survived as well as it has without the neighboring Ben Lomond mountain community. They thank their neighbors for embracing the Veterans Village and helping anyway they could.

“Particularly during the storms,” states Keith. “They were feeding the guys and helping clear the property when trees fell down. They were out here with tractors, saws, everything. We really thank the community of Ben Lomond.”

It’s a phrase heard a lot when speaking with veterans and staff at the Village and downtown Vets Hall. The tight relationship the nonprofits have with the community is a sustainable way to continue giving back to one another.

Let The Good Times Roll

“Before I got here there were very few community events,” Pedley says of the SCCVMB’s weekly calendar.

“Now the calendar is packed every day, barring Monday nights because nobody wants to do anything on Monday nights, which is fair.”

On any given day at the downtown building the community is open to check out the various classes offered: fencing, yoga, dance, meditation, guitar lessons and the list goes on.

“A lot of my clients now are the lost children of abandoned buildings,” explains Pedley, saying that many of the classes arrived when other places were closed after the pandemic. Others because of being pushed out after their buildings were sold to make way for the current downtown construction.

“Two years on, their businesses are thriving because we gave them a space to do that.”

In addition to community courses, the hall is also rented out for birthday parties, quinceañeras, baby showers and sometimes all three.

“Earlier in the year we had a 30th birthday party and baby shower for a woman,” says SCCVMB Events Coordinator, Joel Haston.

“That same woman said she had her quinceañara at the Vets Hall 15 years prior. Like, that’s cool. It’s a story she can tell forever.”

Haston is also the founder of Pin-Up Productions and one of the main reasons the hall has returned to hosting all-ages music events of all genres. Throughout the decades, the building has been the host to many international acts like punk bands Rancid and AFI, hardrockers Avenged Sevenfold and locals turned big like Good Riddance and Drain. More recently, in 2021, the Vets Hall hosted shows by hip-hop group CZARFACE—featuring Wu-Tang member, Inspectah Deck—and internationally known hardcore group Turnstile. It also hosted singer/songwriters such as Jonathan Richman and Linda Tillery, jazzman John Santos and a legendary 1966 concert by the Grateful Dead.

Along with modernizing its programs, the SCCVMB has also slowly modernized its equipment and building through self-fundraising and grants. So far they’ve repaired the amps and replaced some of the lighting, but Haston says they still have a long way to go.

“I’d love to purchase a new, state of the art sound system,” he admits. “That’s hopefully a fundraising goal within the next year.”

Many Santa Cruzans, including Haston, have fond memories of growing up and seeing their favorite bands in the main room, or in the upstairs room and basement. All three of which are once again currently open to rent for shows.

“I’m able to be competitive [with room rental prices] because everything we do here goes back to the veterans,” he says. “We don’t get government funding so everything we make goes to staying open and providing services for the veterans.”

“It might be silly,” says Cottingham. “But I see it as every bottle of water we sell is feeding a veteran.”

As the SCCVMB continues to grow and evolve they are hoping to continue to come up with new and creative ways to fundraise. They are currently fixing up an espresso cart and have plans to open up a cafe in the building sometime in the very near future.

Cottingham also tells GT that the Watsonville Veterans Memorials Building recently held its first veterans services day and it was met with “an overwhelming response.”

However, at the end of the day, the nonprofit not only relies on money to fund these programs but also the charity of the greater community they want to continue serving for years to come.

“Everyone always asks what we want when we come back from the service,” says Pedley. “Honestly, all we want is to be a part of the community again.